When Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, he did something extraordinary for a speaker mounting a challenge to the existing order: he positioned those in his movement not as outsiders and dissidents, but rather as inheritors, indeed as the true inheritors, of the American Constitutional tradition.

He laid hold of the “mystic cords of memory” that connect each generation of Americans. King—who had disobeyed the ordinances of many localities, defied the laws of many states, and written from the cell of a city jail—enveloped his cause and his message in the mantle of mainstream Americanism.

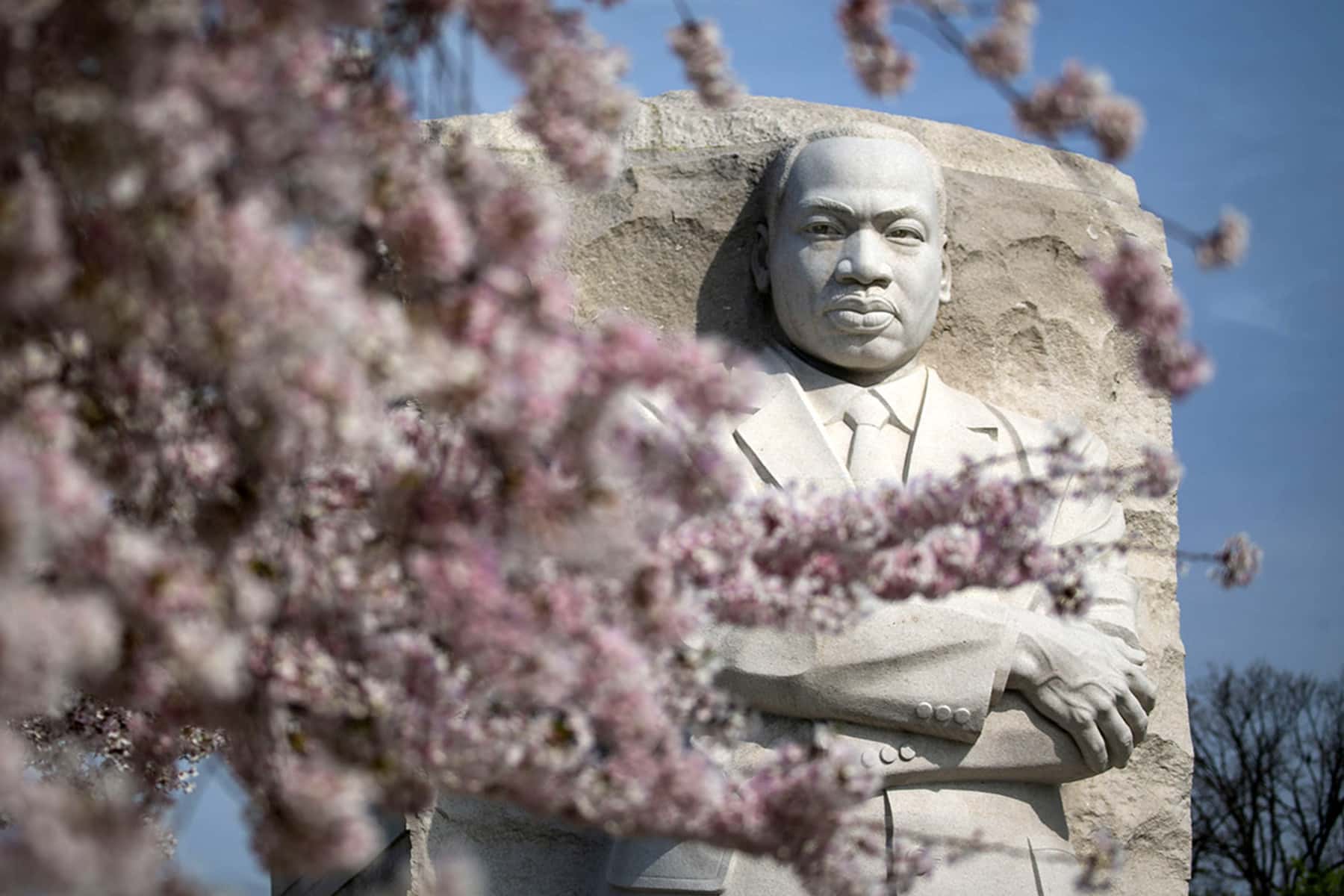

He began the heart of his speech this way: “Five score years ago, a great American in whose symbolic shadow we stand signed the Emancipation Proclamation.” With these words, King associated his message with words chiseled into stone on that very spot, words with which Abraham Lincoln had done at Gettysburg precisely what King was setting out to do: to reimagine America.

With 265 words at Gettysburg, as author and historian Gary Wills noted, Lincoln reinvented America. By transporting his listeners back four score and seven years to the Declaration of Independence in the summer of 1776, Lincoln claimed the Declaration’s commitment to equality as the true founding covenant. Lincoln understood that the Constitution was complicit with the sin of slavery, but he also understood that “Hypocrisy may commit itself beyond easy retraction,” to use Constitutional law expert Charles L. Black’s powerful phrase.

King quite deliberately followed Lincoln’s example, choosing to read the history of America in its most favorable light, then laying claim to those best, deepest instincts of the American founding and using them for his own purposes:

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note … [a] promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

King rhetorically associated the civil rights movement with America by evoking the iconographic image of America itself. In his brief speech, King visualized the geography of America more than a dozen times: from the hilltops of New Hampshire to the peaks of California, from the Rockies of Colorado to Stone Mountain of Georgia. And when the time came to close with a vision that will be recalled until time shall be no more, he explicitly said of his dream: “It is a dream deeply rooted in the American Dream.”

As he invoked Americanism, King also infused it with elements of the African American tradition that had always been a largely unacknowledged part of the nation’s ethos. As the civil rights leader and congressman from Georgia John Lewis was to note, King invited the entire nation into a black church and transformed the steps of the Lincoln Memorial into a pulpit. When King spoke, he created a kind of spiritual communion, making those who watched on the three national networks participants in the moral fervor, freedom songs, spirituals, and impassioned oratory of a civil rights mass meeting, one rich with energies bubbling up from the depths of African American cosmology.

King made clear in his speech that it was not a culmination: “1963 is not an end, but a beginning.” His vision did not end with the transformed Americanism he so skillfully invoked at the Lincoln Memorial. “If we are to have peace on earth,” he said on Christmas Eve 1967, “we must develop a world perspective.” In the ensuing years, he took positions that many would label anti-American. His greatest act of courage may have been his boldness in challenging the Vietnam War, opposition that was in fact one of the better parts of the American tradition. And King was soon to confront forcefully the unfairness of an American economic system that left so many in poverty. In his too few remaining years he began to expand his vision far beyond the Americanism he had skillfully and strategically invoked in his “dream” speech.

Too little attention has been paid to King’s emerging sense of interconnection in the years after the march. Earlier, from Birmingham, he had responded to the charge that he was an “outside agitator” by proclaiming “the interrelatedness of all communities,” stating that, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” After the march, King moved toward a fuller cosmology of unity, expanding upon the claims he’d made in Birmingham to say that, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.” In 1967, he proclaimed, “It really boils down to this: that all life is interrelated.”

He rejected the disaggregated worldview expressed by The New York Times editors who harshly criticized King’s opposition to the Vietnam War for being hurtful to the “cause of Negro equality.” The Times said that by “fusing … two public problems that are distinct and separate,” King had “done a disservice to both.”

King knew better. His vision connected racism with war and poverty, stressed the unity of peoples and movements around the planet, and recognized he interwoven nature of the universe, which he described as “the interrelated structure of all reality.” King’s view of existence as a “network of mutuality” should be recognized as an early expression of systems thinking and ecological consciousness. King’s culminating vision not only linked social justice issues but created a cosmology of justice. He located the imperative for justice in the structure of the universe in a way that may yet provide guidance for our future.

Drew Dellinger and Walter Dellinger

Originally published by YES! Magazine as Why MLK’s Dream Took on Poverty and War Along with Racism