In the summer of 1930, Mrs. Louise Kimbro, a 57-year-old African American woman from Columbus, Ohio, boarded a train for New York City. She was one of 6,685 women who accepted the government’s invitation to join the Gold Star Mothers and Widows pilgrimage between 1930 and 1933. Her son, Private Martin A. Kimbro, had died of meningitis in May 1919 while serving with a U.S. Army labor battalion in France, and his body lay buried in one of the new overseas military cemeteries. Now she would see his grave for the first time.

The journey was enabled by legislation signed by President Calvin Coolidge on March 2, 1929, just before he left office. It authorized mothers and unmarried widows of deceased American soldiers, sailors, and marines buried in Europe to visit their loved ones’ final resting places. All reasonable expenses for their journey were paid for by the nation.

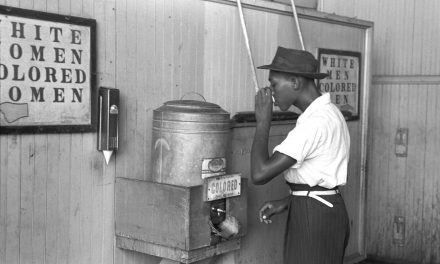

Newspapers promoted the democratic spirit of the event, reminding the public that all the women, regardless of religion, social status, income, or place of birth, were guests of the U.S. government and would be treated equally. In early 1930, however, President Herbert Hoover’s administration announced that “in the interests of the pilgrims themselves,” the women would be divided into racially separate groups but that “no discrimination whatever will be made.” Every group would receive equal accommodation, care and consideration.

Hoover’s staff did not anticipate the political backlash awaiting the War Department once these intentions were revealed. Inviting African American women to participate on these terms required their acquiescence to the same segregated conditions under which their sons and husbands had served during the war. The ensuing protest by the black community, though largely forgotten today, prefigured events from the civil rights movement decades later.

Walter White, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), held a press conference in New York City just as the first ship carrying white women to the cemeteries was sailing out of the nearby harbor. He explained that his organization had written to all eligible black Gold Star mothers and widows encouraging them to boycott the pilgrimage if the government refused to change its segregation policy.

Consequently, hundreds of cards were sent to the secretary of war with signatures protesting the government’s plan, along with a separate letter directed to the president, vehemently objecting to the proposal. Signed petitions from around the nation began arriving at the War Department, claiming that “the high principles of 1918 seemed to have been forgotten.” Others reminded policy makers that “colored boys fought side by side with the white and they deserved the due respect.”

One resentful Philadelphia mother asked, “Must these noble women be jim-crowed, [and] humiliated on such a sacred occasion?” Undeterred, the Hoover administration insisted that “mothers and widows would prefer to seek solace in their grief from companions of their own race.”

But this rebuttal failed to satisfy black mothers, who continued to send in their petitions as part of the NAACP’s efforts. They claimed they would decline to go at all unless the segregation ruling was abolished and all women could participate on equal terms. The NAACP campaign, threats that black voters would switch to the Democrats, and even the adept pen of W. E. B. Du Bois ultimately failed to alter the government’s stance.

In a sharp assault, Du Bois referred to the more than 6,000 African Americans whose “Black hands buried the putrid bodies of white American soldiers in France. [Yet,] Black mothers cannot go with white mothers to look at the graves.” Walter White had hoped that when the mothers and widows understood the separate conditions governing their travel, they would “repudiate the trip.” For some mothers, however, refusing the government’s invitation was one sacrifice too many. Most seem to have signed the petition without intending to forfeit this unique offer. When they were forced to choose between motherhood and activism, motherhood prevailed.

The number of eligible African American women was, in the event, too small to influence policy. Approximately 1,593 black mothers and widows were deemed eligible to make the pilgrimage. Many declined, largely because of ill-health, death or remarriage. Only 233 accepted the invitation, and fewer than 200 actually sailed.

For those who went, traveling posed challenges: most of the women were mothers in their 60s, but a number were over 70 and in failing health. Some were so poor that they were unable to buy even the suitcase necessary for the trip, and most had never traveled so far on their own. And for women like Louise Kimbro, who endured a 24-hour train journey across a segregated nation before boarding a ship to Europe, there were additional hardships involved.

With no luggage racks in the “colored” section of the train, passengers were forced to cram their suitcases around their feet in the crowded compartments. “Colored” train bathrooms were smaller and lacked the amenities of the “whites” bathrooms, and while traveling through Southern states, women were required to move to “colored only” railcars so that white passengers could board.

On arrival in New York, African American women were accommodated at the YWCA hostel, rather than the more comfortable Hotel Pennsylvania where white pilgrims stayed. The African American women who embarked on the SS American Merchant, a freighter-passenger vessel (rather than a luxury liner), hailed from a variety of states and social backgrounds, from illiterate women to college graduates. They were escorted by Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Sr., the army’s highest-ranking black officer.

Once they landed in France, separate trains carried African American and white pilgrims to Paris, where they were welcomed at the station by the trumpeted notes of “Mammy,” played by Nobel Sissle’s orchestra. The African American women enjoyed many of the same elegant restaurants and receptions offered on the white women’s itinerary but were again lodged in different hotels, since French hoteliers hesitated to accept black women for fear of offending some of their white American clientele.

Most women returned from their pilgrimage without regrets. One Georgia mother told reporters, “Every effort was made to get me not to come. I think it is a shame that some mothers were induced not to come by people who had nothing to lose, and who, if they were in our places, would certainly have come.” No one seems to have publicly challenged those who accepted the government’s offer, which required of them a compromise that white mothers and widows had not been asked to make.

It is estimated that 23 women, their identities no longer known, refused the invitation at the urging of the NAACP. Although they may not have achieved their objective of an integrated pilgrimage, this minority of older and mostly poor, uneducated black women had challenged the injustices of Jim Crow and succeeded in shifting the balance of power nationally by questioning the hypocrisy of the program and the violation of the democratic principles over which the war had been fought.

Lіsa M. Budrеаu

National Archives and Records Administration

Excerpt from “Gold Star Mothers” by Lisa M. Budreau, We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity, © Smithsonian Institution