Lower turnout in Wisconsin’s biggest city helped Trump to victory in 2016, and Joe Biden must engage Black voters and overcome voter suppression to carry the crucial state’s electoral votes.

Many Americans were stunned when Donald Trump narrowly defeated Hillary Clinton in Wisconsin in 2016. Greg Lewis was not. In the months leading up to the election, Lewis, an assistant pastor at St Gabriel’s Church of God in Christ in Milwaukee, the state’s largest city, would drive up and down highways crisscrossing Wisconsin and all he saw were Trump posters. But in the city, where Lewis runs Souls to the Polls, an interfaith effort to get parishioners to vote, no one gave the churches the resources to organize.

On election day, turnout in Milwaukee, home to a majority of the state’s African American population, dropped by just over 41,000 votes. Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in the state by just under 23,000 votes. He was the first Republican presidential candidate to carry the state since Ronald Reagan in 1984.

There are few cities in the US more important to the 2020 election than Milwaukee, which could play a critical role in deciding who wins the key battleground state of Wisconsin and the presidency. Joe Biden will probably win the vote in the Democratic bastion, but the number of voters who turn out there could dramatically influence his chances of winning statewide.

Milwaukee is an “essential part” of the coalition any Democrat needs to win a statewide election, said Barry Burden, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who runs the Elections Research Center. A small change in turnout in the city is more consequential for Democrats than it is for Republicans. Because of those consequences, the city has been the target of some of the most brazen Republican-backed efforts to suppress voting rights in the United States. This, coupled with a lack of genuine engagement in minority communities, was behind the 2016 drop in turnout, activists said.

Lewis, who has snow-white hair and a matching bushy beard, thinks there were enough untapped votes in Milwaukee’s churches alone to change the outcome of the election. “Most of these people don’t believe that the system works for them. They don’t trust the system, they don’t believe in the system. That’s what we have to fight internally,” he said. “Externally, we have to fight disenfranchisement and suppression of our vote.”

Wisconsin voters say their lack of enthusiasm for Democratic candidates stems from feeling forgotten by the party. Milwaukee is one of the most segregated cities in America, and some of the biggest drops in 2016 turnout were in Black neighborhoods of the city, including the 53206 zip code, one of the poorest areas.

“Simply put, if Democratic institutions in Wisconsin would have paid attention to Black and brown communities in ways that weren’t superficial, Republicans, Trump in particular, wouldn’t have won,” said Jarette English, a local activist in Milwaukee.

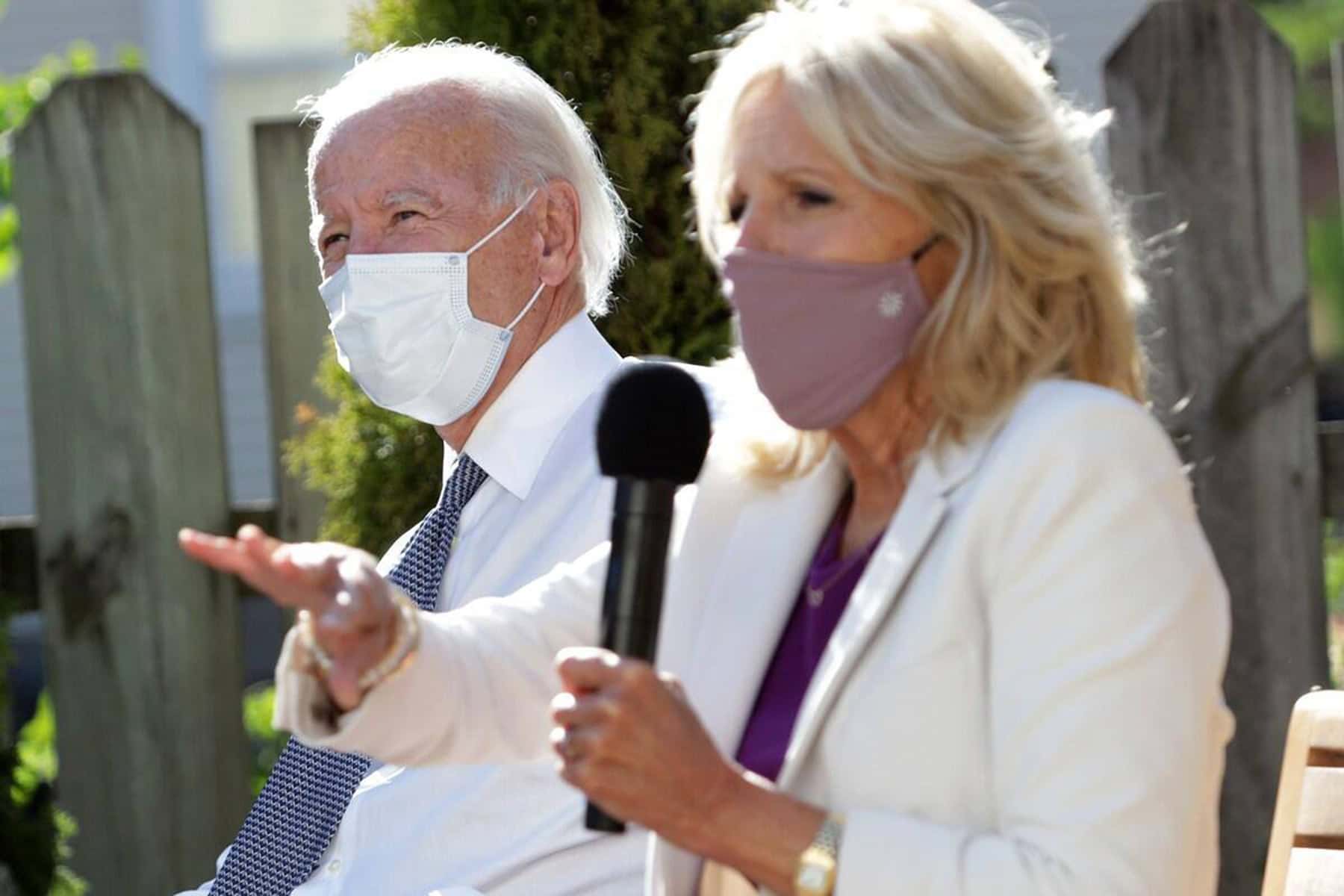

Clinton, who blames voter suppression for her loss in Wisconsin, infamously didn’t travel to the state after the 2016 primary. This year, Biden made his first trip to Wisconsin earlier this month when he visited with the family of Jacob Blake, a victim of police violence, at the Milwaukee airport. It was the first time Biden had traveled to the state since 2018, according to ABC News, and the first time a Democratic presidential nominee visited Wisconsin since 2012. Kamala Harris, the Democratic vice-presidential nominee, spent Labor Day in Milwaukee.

“Morale around voting is currently fluctuating. In 2016 it was definitely in a downward spiral. People are tired of voting for candidates who bring little to no change. Folks don’t see their everyday life and issues change, so the attitude is ‘why continue to participate?’” said Vaun Mayes, an activist in the city.

With only a few until election day, some activists say there could still be a lack of enthusiasm this fall. Black voters in Milwaukee, which has extremely high incarceration rates for African American men, are wary of the record of Biden and Harris on crime issues, Lewis said. “Folks are not excited about who’s running,” said Amanda Avalos, senior civic engagement director for Leaders Igniting Transformation, an activist group focused on helping young people organize.

But a lack of interest does not entirely explain the drop in turnout in Milwaukee. There are also severe, Republican-crafted, barriers to voting that remain in place. Over the last decade, Milwaukee – which is nearly 40% Black – has been the target of some of the most brutal attacks on the right to vote. After taking control of the Wisconsin legislature in 2011, state Republicans quickly passed a voter ID law, curtailed early voting – a process frequently utilized by minority voters – and made it harder for third parties to register voters. Republicans also drew electoral districts in such a way that virtually guaranteed the party would maintain control over both chambers of the state legislature.

The voting changes combined with that aggressive effort have cemented Republican control in the state for the last decade. It is no secret that Republicans enacted these changes to target Milwaukee and its Democratic voters. Republicans have said so themselves. “The question of where this is coming from and why are we doing this and why are we trying to disenfranchise people, I mean, I say it’s because the people I represent in the 13th district continue to ask me, ‘What is going on in Milwaukee?’” Scott Fitzgerald, the Republican leader in the senate, said of an effort to limit early voting.

“We’ve got to think about what this would mean for the neighborhoods around Milwaukee and the college campuses,” one Republican state senator reportedly said during a closed-door meeting where lawmakers appeared “giddy” at the prospect of the new law, according to a former staffer.

In 2016, Judge James Peterson of the US district court wrote that many of the voting changes Republicans enacted were “specifically targeted to curtail voting in Milwaukee without any other legitimate purpose. The legislature’s immediate goal was to achieve a partisan objective, but the means of achieving that objective was to suppress the reliably Democratic vote of Milwaukee’s African Americans.” (Parts of Peterson’s 2016 ruling have since been overturned).

In Milwaukee, where more than a quarter of the population lives in poverty, even a small change around voting can make a huge difference, said Shauntay Nelson, the director of the Wisconsin chapter of All Voting is Local, a group that works on improving access to the polls.

“There are a lot of people within the city of Milwaukee who may work two jobs and are not able to get off of work and have enough time to get to the department of motor vehicles,” she said. “There historically has been so much hardship within Milwaukee, individuals may not be able to pay attention to changes that are happening.”

The 2016 election was the first presidential contest the state’s new voter ID law was in effect. It appears to have worked as Republicans hoped. While it can be difficult to measure the reasons people don’t vote, as many as 23,252 people were deterred from voting by the law in Milwaukee and Dane counties, the two largest in the state, according to a study by researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

African Americans and poor people were all much more likely to point to voter ID as a reason they didn’t vote. Part of the problem was confusion over the complicated law – the researchers found that the majority of people who said they lacked acceptable ID, actually had one. The state did an abysmal job of educating people about the new voter ID law ahead of the 2016 election, said Claire Woodall-Vogg, the executive director of the Milwaukee election commission. Part of the state’s education plan, she noted, involved running public service announcements in movie theaters throughout the state, but none of them were in Milwaukee.

“Confusion itself has deterred some voters and also created a mistrust in that system,” she said.

This year, Milwaukee, has also been one of the hardest-hit places by COVID-19 in Wisconsin and there are worries the virus will only exacerbate the already-severe barriers that exist to voting. In April, when Wisconsin held its statewide election, Milwaukee was forced to close all but five of its approximately 180 polling locations because of a shortage of poll workers – the city was able to open 168 locations for the state’s August primary. Nelson said she continued to be worried about recruiting enough poll workers for November.

Meanwhile, Lewis, who was alarmed ahead of the 2016 election, said he was optimistic that Souls to the Polls and other organizations would drive voter turnout. Since 2016, activists in the city have made an aggressive effort to canvass some of the poorest neighborhoods to engage residents and connect voting to improving their lives. But he expressed frustration that Biden had yet to campaign in the critical city, even after Covid-19 forced the party to scrap plans to host the Democratic national convention there.

“I would like our candidate to at least step on the earth of Milwaukee,” he said. “I don’t know what it’s gonna take for them to understand that you’ve got to play as hard as everybody else if you expect folks to support you and have the energy to really build up a grassroots effort to get out the vote.”

Sаm Lеvіnе and Isiah Holmes

Kеrеm Yucеl

Portions originally published on The Guardian as Why Milwaukee could determine Joe Biden’s fate in November’s election

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.