By Deadric T. Williams, Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Tennessee; Armon Perry, Professor of Social Work, University of Louisville

“The flaw with ‘comply or die’ argument about confrontations with law enforcement is that Black men can expect to die even when they do comply. And Kenosha is an unvarnished example of White Militias actually are, a modern incarnation of the KKK. Gone are the hoods, and in place are patriotic manifestos and high-powered military weapons of war. It is the same campaign of terror, wrapped in a flag instead of white sheets.” – Maxwell Kaufmann

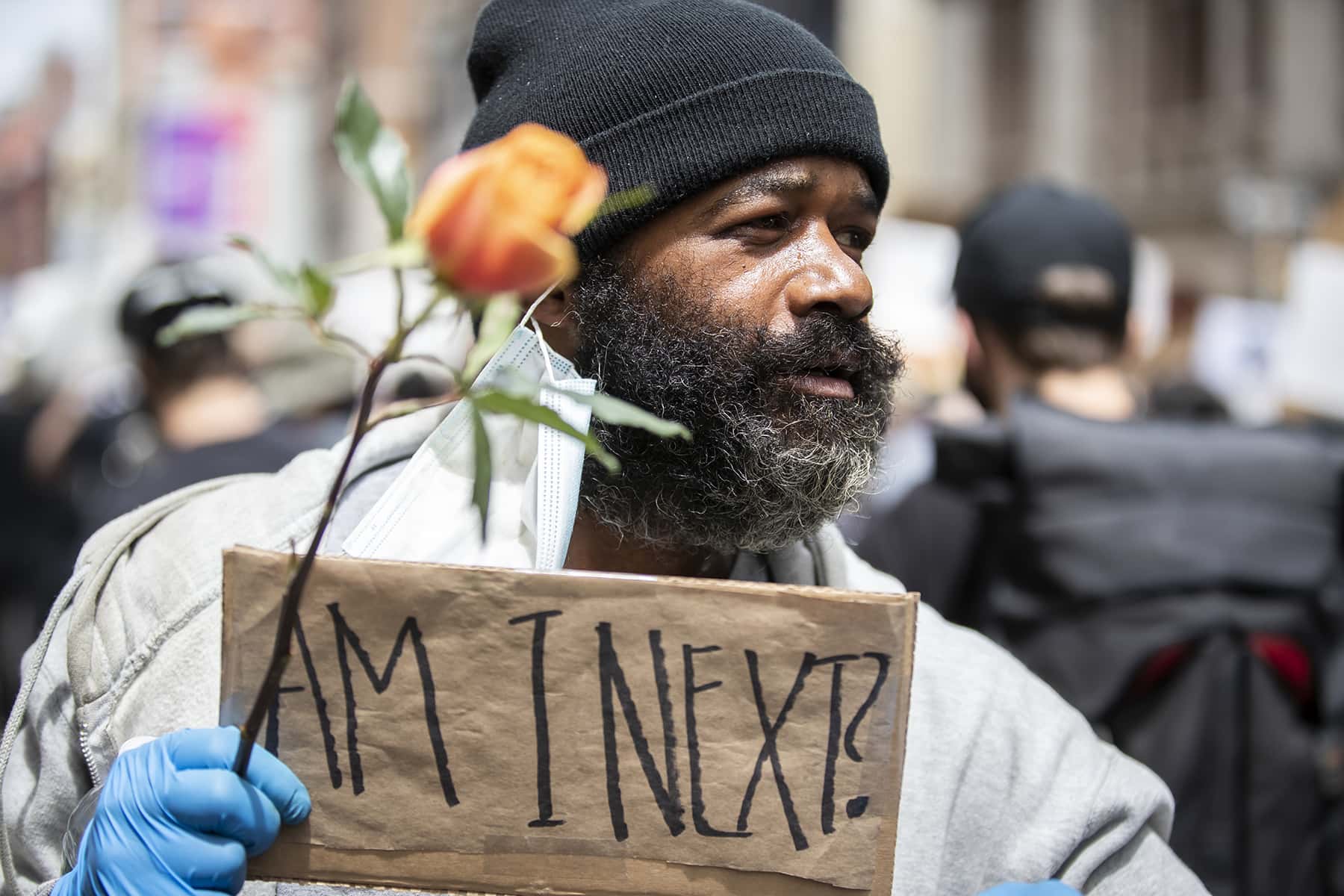

While much of the world was sheltering in place in the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, many Americans’ undivided attention was focused squarely on Minneapolis, Minnesota, where George Floyd was killed at the hands – and knees – of the police.

Floyd’s murder evoked memories of other murders by the police, including those of Walter Scott, Eric Garner, Philando Castile and Samuel DuBose. Most recently, another unarmed Black man, Jacob Blake, was shot seven times in the back in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

We are a sociologist and a social worker who study racism, inequality and families, including a focus on Black men and their interactions with law enforcement. Each of these killings serves as confirmation that concerns about those interactions are warranted.

The problem isn’t just that Black men get killed – it’s that Black families are stressed and strained by Black men’s daily encounters with police. Studies show Black and Hispanic drivers, compared to white drivers, experience a disproportionate number of police stops and that officers show less respect to Black drivers.

Racial inequality in contact with the police may influence the lack of trust in police among Black Americans. In a recent Gallup survey, one in four Black men ages 18 to 34 reported they have been treated unfairly by police within the last month.

In our research on these interactions, we found that they have far-reaching implications for Black families. Law enforcement encounters for Black Americans stretch beyond the streets of our cities and into Black Americans’ homes, where they have a negative effect on family life.

Families suffer

Studies show that one in nine Black children has had a parent in prison. Having an incarcerated parent is associated with a host of social problems for children, including behavioral problems and academic failure.

Former inmates have to navigate many barriers to reintegrate and reconnect with their communities and families. A recent study shows that if fathers were previously incarcerated, they were more likely to report having a strained and unsupportive relationship with their child’s mother, a major factor which negatively impacts fathers’ involvement and harms their connection and relationship with their children.

Although a growing number of studies focus on incarceration and families, there is less empirical research that includes whether police stops experienced by Black fathers affect family life. In our research, we have found the obstacles that come with economic hardship, mental illness, parenting stress and incarceration can hurt how well parents work together and the well-being of their children.

We wanted to extend our work by examining whether experiencing a traffic stop for Black fathers affected their relationship with their child’s mother. This is important because the mother-father relationship plays a large role in fathers’ involvement with their children.

In 2019, we co-authored a study that examined how Black fathers’ contacts with police affects their relationships with their children’s mother. We analyzed data from the Fragile Families and Child Well-being study, a study surveying nearly 5,000 families from urban cities. In conducting our analysis, we focused on 967 Black families that included both fathers’ and mothers’ reports of relationship quality and cooperative parenting.

We found that fathers who reported experiencing a police stop were more likely to report conflict or lack of cooperation in their relationships with their children’s mother. They also reported the same relationship problem if they had been previously incarcerated.

Anger and frustration

Encountering law enforcement can affect family relationships in a number of ways. In many cities, the police presence is heaviest in low-income communities where Black men are more likely to live. These communities and their residents are often economically disadvantaged with very few viable prospects for gainful employment.

For the Black fathers in these communities, not being able to fulfill the financial provider role can contribute to relationship tension with their children’s mother. Family researchers suggest that stressful events such as law enforcement contact may also reduce individuals’ ability to manage family problems.

Family members are inextricably linked, so when Black fathers experience a police stop, it may generate feelings of uncertainty and agitation on the part of the mother and affect the way that she views the relationship, leading to anger and frustration that negatively impacts the relationship.

Reinforcing racial oppression

The disproportionate number of Black men who have contact with law enforcement does not happen within a vacuum. Some researchers underscore the historical origins of policing and criminalizing of Black males since the Civil War that continues into the present. This includes negative stereotypes of Black men as dangerous, which led to more than 150 years of lynchings, mass incarceration of Black men and more recent stop-and-frisk policies that disproportionately target Blacks.

Given the prevalence of both incarceration and police stops for Black men, law enforcement contact of any kind can become a source of additional stress and may reinforce racial oppression. As the results of our study indicate, these experiences may carry over into their day-to-day lives, including harming their family relationships.

Irа L. Blаck and Brаndоn Bеll

Originally published on The Conversation as When police stop Black men, the effects reach into their homes and families

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.