A fugitive slave ad from just over 200 years ago reads: “Run away from the subscriber in Albemarle, a Mulatto slave called Sandy. His stature is rather low, inclining to corpulence, and his complexion light; he is a shoemaker by trade, in which he uses his left hand principally, can do coarse carpenters work, and is something of a horse jockey… Whoever conveys the said slave to me, in Albemarle, shall have 40 s. Reward.”

Placed by future president Thomas Jefferson, the ad in search of the runaway Sandy is one of more than 27,000 collected so far by Freedom on the Move, a historical open source database launched at the Cornell Institute for Social and Economic Research in 2019.

Tens of thousands more, buried in the archives of small libraries, historical societies, and churches across the South, have yet to be catalogued. Together, the ads — some posted by enslavers, others by jailers holding suspected escapees — detail a primary means of Black resistance and resilience over nearly 250 years of slavery.

The picture they form is expansive, but not without flaws, said Dr. Vanessa Holden, a member of the interdisciplinary team leading the Freedom on the Move project and assistant professor of history at the University of Kentucky. “You’re reading the details that an enslaver cared about most. You’re not reading how [those who were enslaved] would describe themselves,” she explained.

But the database is nonetheless a powerful tool, the first of its kind to provide insight into the individual experiences of enslaved men, women, and children who have long been excluded from historical records and buried by narratives of the past.

The ads, Holden said, “are a testament to the amount of widespread resistance to slavery.”

Slavery is synonymous with the founding of America. But those who were enslaved — Black and Indigenous, alike — did not passively accept their servitude. According to Between Slavery and Freedom by Julie Winch, they used any strategy they could to self-liberate, including running away from their enslavers, cultivating small patches of land, or working at a skilled trade to earn the money to buy their freedom.

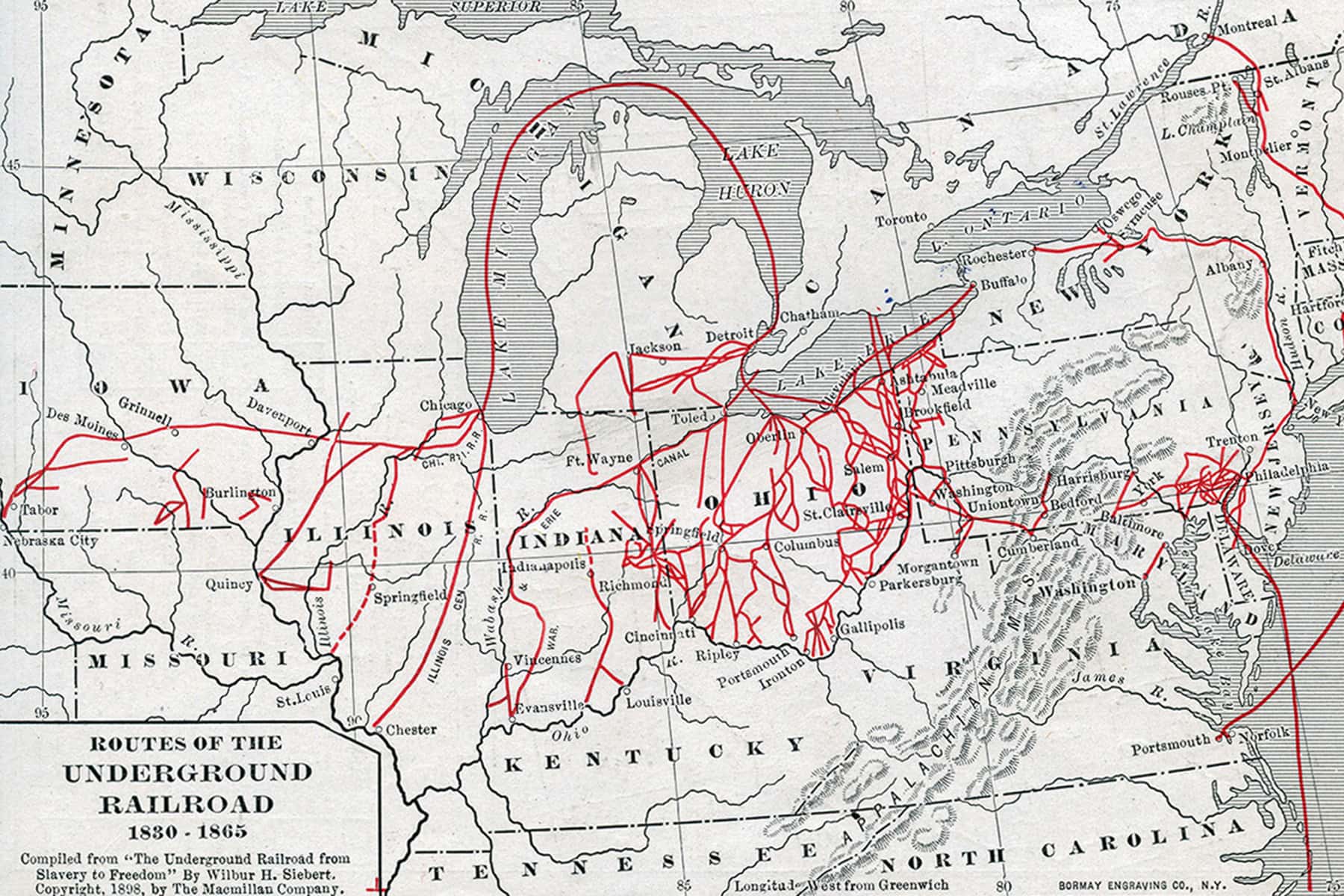

One of the most common forms of resistance against slavery were attempts by the enslaved to flee from bondage. Some self-emancipated individuals ran to Native American nations in search of freedom. Others attempted to blend into communities of freedmen, or Black people who were not enslaved, in cities such as Charleston and Baltimore, or headed to frontier lands where they could more easily hide. Still others enlisted the help of networks of abolitionists up and down the Eastern Seaboard to cross the border to Canada or board a steamer for Europe. Nevertheless, by 1790 and the first American census, 92% of the more than 757,000 Black people in America were enslaved, Winch writes.

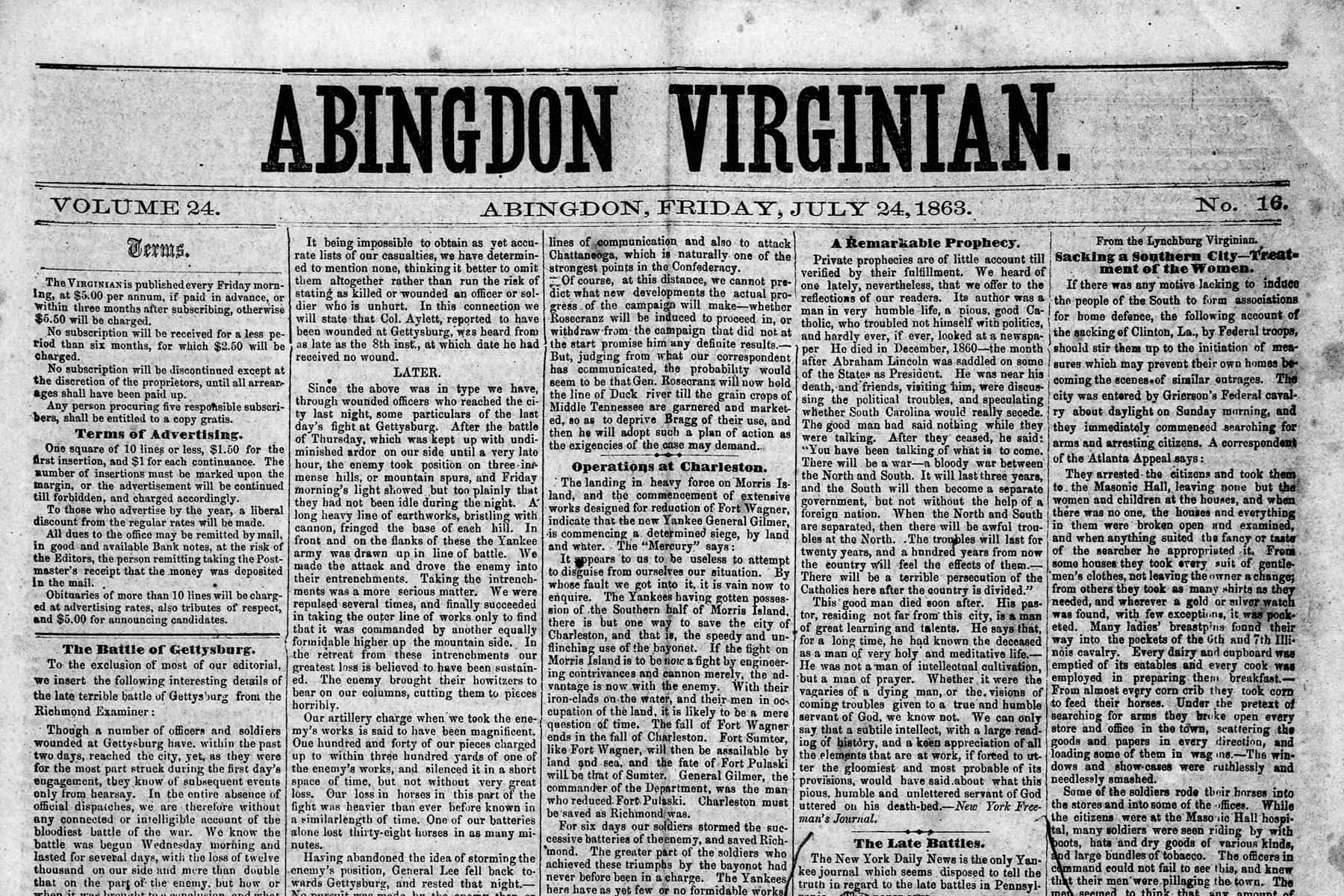

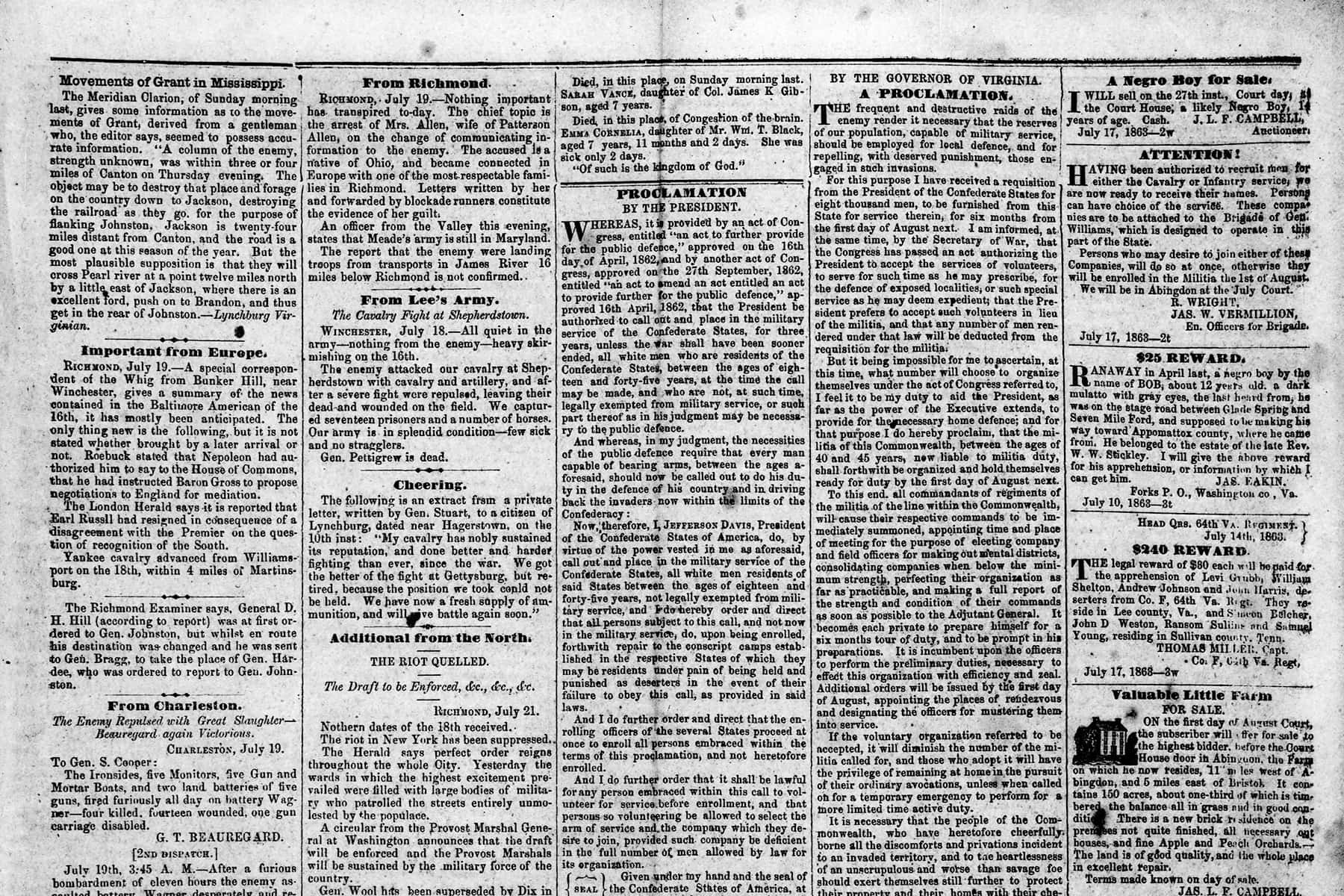

While there is no way to know exactly how many individuals escaped or attempted to escape during the era of American slavery, fugitive slave ads appeared daily in newspapers large and small throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. The vast majority begin with a detailed description of the runaway’s physical characteristics, including the shade of their skin, their gait or posture, their age, and any identifying scars or injuries.

Some of the ads mention what the slave was wearing when they absconded, what they might have carried with them on their journey, or where they might have been headed. Those posted by enslavers or their agents typically offer a reward for anyone who can apprehend the fugitive. Those posted by jailers request payment for the care proffered during the presumptive escaped slave’s imprisonment.

These latter ads are among the most fraught of the collection. “Just because somebody was picked up as truant or runaway and was held by a jailer doesn’t mean they actually were someone who was a fugitive from slavery, it means that they were suspected,” Holden explains. This is especially true considering that, at the time, free Blacks were regularly targeted by kidnappers who sold them into slavery in the South.

The target audience for the ads was the whole of White society. Fugitive ads “really trained White people to inspect and question Black people, to question whether or not they should be in a public space, to question if they should be walking along a road or not, to demand that they prove their validity,” Holden said. They “teach people to see race [and] distinguish African-descendant people as appropriate for slavery.”

But while the ads helped to uphold the socioeconomic system of racial hierarchy in the past, today they are treasured for the wealth of information they contain about exactly who the individuals forced into slavery were, how they escaped, and where they were headed.

“I have made the analogy that [the ads] serve as a de facto census of a population that 19th century censuses failed to capture in detail,” said Dr. William C. Block, Freedom on the Move team member and the director of Cornell Institute for Social and Economic Research. They can help to form a “more nuanced understanding of the reality of life during slavery.”

The ads also help to challenge accepted narratives such as the belief that those who self-emancipated were overwhelmingly men. As researchers, citizen historians, teachers, and students work to digitize the collection, they are discovering instances in which women are mislabeled as men in the ad’s accompanying stereotype images, in which women fled with a male companion, or in which women disguised their gender to escape. These are just some of the ways that we may have been missing women all along, Holden said.

In addition to forming a more complete picture of slavery and the enslaved, one of the primary goals of the Freedom on the Move database has been to engage students, not just at the university level, but in K-12 too, in the complexities of American history. In collaboration with the Hard History Project, Freedom on the Move has developed four history lessons adaptable for children in grades three to 12. On June 3, more than 40 K-to-12 educators participated in a webinar about using the materials in the classroom.

Freedom on the Move hopes that introducing younger students to slavery early will help to expand their understanding of the origins, and persistence, of racial injustice in the United States. Providing students with the opportunity to contribute to the archive is a powerful way of bringing history alive. They, along with thousands of other individuals, more than 8,874 altogether so far, have added to the database, scanning and uploading fugitive slave ads and coding their information into searchable formats.

While the database will be invaluable to historians once it’s complete, Freedom on the Move does not claim ownership over the materials. They can be read, searched, and used by anyone who is interested. This is particularly important in the contemporary moment of racial reckoning in the United States.

By illuminating the experiences of those whose lives were bound by slavery, Block hopes the Freedom on the Move project will help to shine a light on their descendants, too. In many ways, society still conditions Americans to participate in surveilling some members of the community, Holden said.

Though the moment is different, echoes of slavery still exist.

Library of Congress – Chronicling America Online Collection

Originally published by YES! Magazine as What Fugitive Slave Ads Reveal About the Roots of Black Resistance in the United States