U.S. Files Suit on Vote Rights: Tallahatchie County Facing Charges That Negroes Barred From Polls

“There are 5,099 whites and 6,483 Negroes of voting age in Tallahatchie County…about 4,300 whites and no Negroes are registered to vote.” – Memphis Commercial Appeal Newspaper, November 21, 1961

Advocates plan to register more voters after latest attempt to suppress Wisconsin elections

“A Wisconsin judge ordered on December 13 that the registration of up to 234,000 voters be tossed out because they may have moved, a victory for conservatives that could make it more difficult for people to vote next year in the key swing state.” – Milwaukee Independent, December 16, 2019

My family is from Tallahatchie County, Mississippi. Looking back at newspaper headlines from November and December 1961 creates an eerily similar response in me as current headlines about the purging of voter rolls in Wisconsin and multiple other states. There is little doubt that this ruling by a judge in Ozaukee County will negatively impact the black population in Milwaukee in elections next year.

In October the state Elections Commission sent letters to 234,000 voters it believed had moved. The letter asked voters to update their voter registrations if they had moved or asked them to say if they were at still the same address. Those who did not respond to the letters were initially scheduled to be removed from the voting rolls in 2021 but the decision will speed up the process and make it happen prior to the 2020 presidential election.

Judge Malloy stated that they should be removed within 30 days. 60,000 of the letters were returned as undeliverable. Over 2,000 responded that they lived at the same address and just over 16,000 had registered at new addresses according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. The letters were mostly sent to heavily Democratic areas like Milwaukee and Madison. Even though the two cities have just 14% of registered voters in the state 23% of the letters were sent there.

Wisconsin is not the only state to purge voter rolls recently. Georgia has removed over 300,000 registered voters this year and removed 1.5 million between 2012 and 2016. This is part of a trend that began after the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder. The 5-4 vote effectively removed Section 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which required certain states and local governments to obtain federal pre-clearance before implementing any changes to their voting laws or practices. They did not eliminate Section 5 but did discard Section 4(b), which contained the coverage formula determining which jurisdictions are subjected to pre-clearance based on their histories of discrimination in voting.

By saying those states, which have a long history of discrimination against blacks no longer, discriminate, the Court ignored the ugly history of these states. Less than five years later without oversight of the Department of Justice these states had reversed much of the progress of the previous decades. Over 1,000 polling places, most of them in black neighborhoods had been closed. They also changed the rules for early voting and purged voting rolls in several states. This did not come as a surprise to those of us in the black community who saw this start literally the day after the decision.

A recent study by the Brennan Center found that “At least 17 million voters were purged nationwide between 2016 and 2018, similar to the number we saw between 2014 and 2016.” The rates were 40 percent higher in states that were formerly required to receive preclearance than those not covered by this part of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. A 2018 study by Brennan found that in “Virginia in 2013, nearly 39,000 voters were removed from the rolls when the state relied on a faulty database to delete voters who allegedly had moved out of the commonwealth.

Error rates in some counties ran as high as 17 percent… (Nationwide) Almost 4 million more names were purged from the rolls between 2014 and 2016 than between 2006 and 2008. This growth in the number of removed voters represented an increase of 33 percent…” In Texas 363,000 more people were purged in the first election after the Shelby decision than in the previous midterm election.

These efforts across the country are being driven by conservative organizations filing lawsuits allegedly on behalf of private citizens. This concerted effort has been effective in shifting the outcomes in elections across the country. The most unfortunate aspect of these purges is that “voters often do not realize they have been purged until they try to cast a ballot on Election Day—after it’s already too late,” according to researcher Kevin Morris. Untold numbers of people in Milwaukee will be unaware of the fact that they were purged if they’ve moved and did not receive the letter.

What sense does it make to send letters to an address where you believe people no longer live, asking them to update their registration? Obviously if they have moved they are most likely not going to see the letter. Even people who receive the letter may disregard it as unimportant and not read it. It’s not often we receive mail from the state Elections Commission. With the huge eviction crisis in the black community documented by Matthew Desmond in his book Evicted, in Milwaukee the impact will be significant.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 has been much celebrated but many are unaware of how difficult it was to get passage in Congress and the battles to maintain it. As I look at these articles about Tallahatchie County where I was born I’m reminded of the many stories I heard about the voter registration efforts in Mississippi.

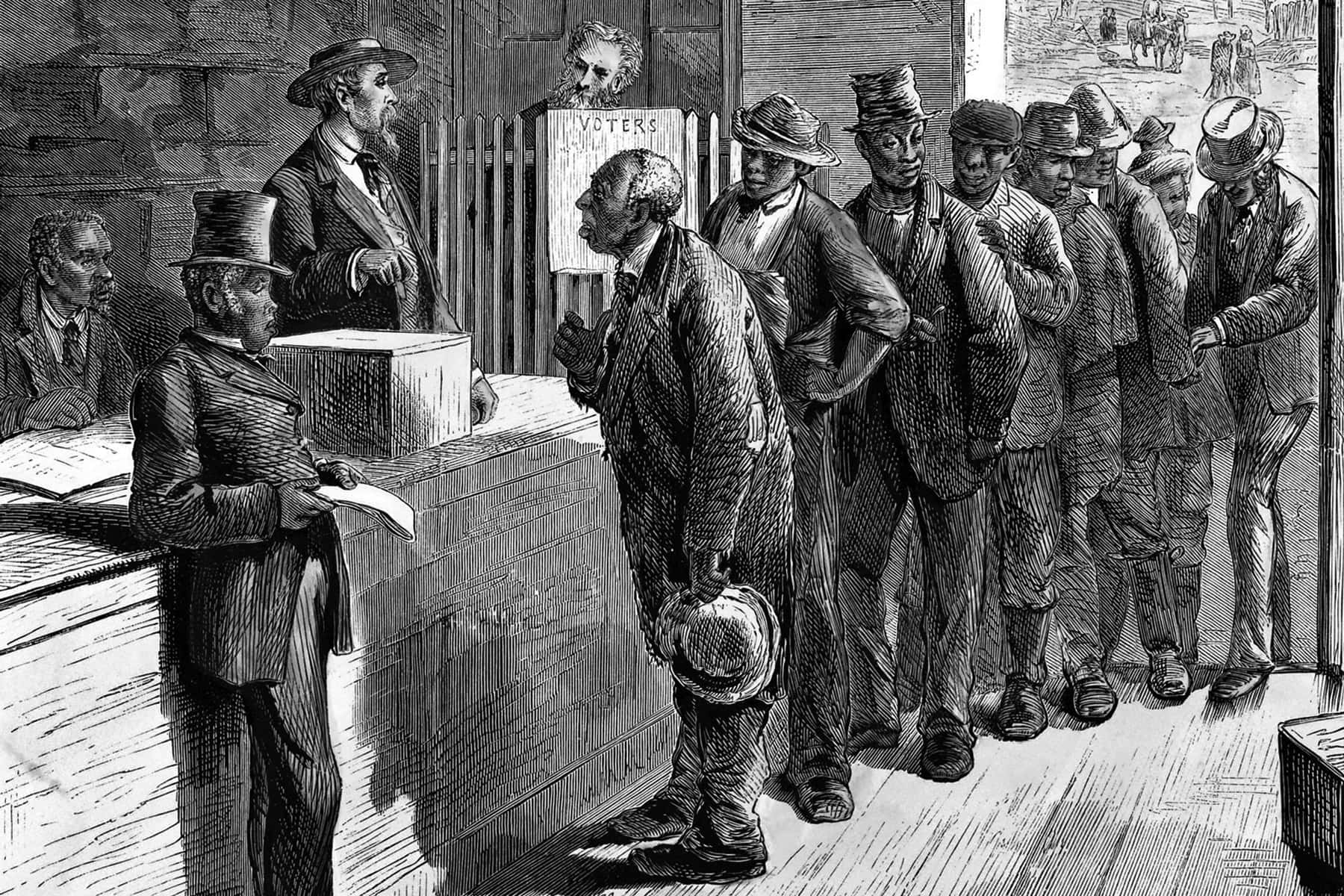

A courageous group of black people in my hometown took it upon themselves to challenge white Mississippians continuing blockage of their right to vote. Data shared with the court showed that since at least 1946 Tallahatchie County officials had prevented poor blacks from paying the poll tax, which would have then allowed them to vote. Whites were allowed to pay the poll tax without restrictions.

“Power only came with the vote. The vote meant equality. It gave us power to choose our elected leaders and power to make demands. When Black folks are cheated out of their right as a citizen to vote, then everybody in this country has been cheated.” – Rev. Dr. C.T. Vivian

The poll tax was a tool of disenfranchisement created to place extra barriers in the way of blacks attempting to vote. For those too poor to pay, registration and consequently voting would not be possible. After decades of this barrier preventing blacks from voting throughout Mississippi, those who had saved money to pay the tax were thwarted in their efforts to register. The sheriff in Tallahatchie County simply disallowed blacks from paying the tax. Not a single black person in the county was registered to vote in 1961 when the suit was filed. Only 7% of blacks in the entire state were registered to vote at that time.

Poll taxes were just one way of preventing blacks from voting in many places in the South. It was not until 1966 in Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, that the U.S. Supreme Court held Virginia’s poll tax to be unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment.

Whites also used so-called “literacy tests”, economic retaliation for registering, white-only primaries, arrests, beatings, bombings, lynchings and assassinations to prevent blacks from voting in counties around Mississippi as well as in other states. Blacks outnumbered whites in many of those counties but had no political power because they could not vote.

A perfect example was Leflore County, Mississippi, not far from my hometown, where less than 300 blacks (2% of black residents) had been allowed to register in 1963 while every white eligible to vote was registered. As a result only 268 blacks were registered and 10,000 whites were registered even though blacks were 60% of the population of the county.

The Ku Klux Klan and White Citizens Councils in the state played a prominent role in suppressing the black vote. The Klan intimidated and even killed blacks that attempted to vote. The White Citizens Councils made sure white employers would fire blacks that attempted to register and that white landlords would evict blacks for being involved in voter registration campaigns.

The Mississippi State Sovereignty (Commission) was created by an act of the Mississippi legislature on March 29, 1956. They developed a network of paid spies to counter blacks efforts to vote and fight against segregation. They used paid informants within the black community including some pastors to get inside information and circumvent black efforts to gain rights. In January 1977, legislators introduced bills to abolish the Commission and dispose of its records and equipment but a lawsuit was filed to prevent destruction of the files. The records are available to the public since the late 1990s and online since 2002.

The Commission’s objective was to:

“do and perform any and all acts deemed necessary and proper to protect the sovereignty of the state of Mississippi, and her sister states…” from perceived “encroachment thereon by the Federal Government or any branch, department or agency thereof.”

These activities and laws made sure that whites would maintain complete control over blacks in every way. Since the end of Reconstruction in 1876, white terror and intimidation helped to maintain white supremacy in every sphere of life in Mississippi and other places in the Deep South.

Allowing blacks to vote in the eyes of most whites was seen as allowing blacks to be “uppity” and trying to be “equal to whites.” As the 1960s began blacks were saying that segregated spaces were an issue that was much less important than voting rights. Amzie Moore and Medgar Evers contacted Bob Moses of SNCC (Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee). They told him it’s time to try to begin registering blacks in the state. Blacks in my hometown like Willie Peacock and Birdie Kegler recognize that voting power leads to political power for black people.

Despite violence and intimidation, voter registration efforts in Mississippi ramp up. The famous Mississippi Freedom Summer campaign of 1964 becomes worldwide news when the police and Ku Klux Klan in Neshoba County murder James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner in June. Only a payment of $30,000 to Klan informant Delmar Dennis who participated in the murders led to the discovery of the bodies buried in an earthen dam. Dennis reportedly was treated to a steak dinner on the night the bodies were found and given immunity form prosecution. Rita Schwerner the mother of Michael recognizes that two of the murdered young men being white led to the national spotlight being shone on the case.

She tells reporters, “I personally suspect that Mr. Chaney, who is a native Mississippi Negro, had been alone at the time of the disappearance, that this case, like so many others that have come before, would have gone completely unnoticed.”

During the search for the young men who were quickly assumed to be dead, Navy divers dragging rivers discovered two young black voting rights activists, Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore. They also uncovered the body of 14-year-old Herbert Oarsby as well as five other unidentified black men.

In Wisconsin the efforts of blacks to vote was prevented by whites for many years as well. The first election in Milwaukee County to elect officials to oversee the county was held in 1835. All white men were expected to vote. Talbet C. Dousman refused. He finally agreed to vote only if “Nigger Joe” could vote too. Officials agreed to let Joe Oliver vote on September 17, 1835. It would be over thirty years before another black person voted in the state.

At the 1846 Wisconsin constitutional convention a motion was made to remove “white” from the voting requirements. A compromise was made to introduce a ballot referendum on allowing black men to vote in the next election. 14,615 voted against and just 7,664 voters were in favor of giving black men access to the franchise. A second referendum in the 1849 general election was placed on the ballot. 5,265 voted in favor of the referendum while just 4,075 voted against it.

It appeared black men would be given the right to vote after the referendum passed. However, the state Election Commission ruled that since most ballots across the state left the question of Negro suffrage blank that those could be assumed to be “no” votes therefore, blacks could not vote. On November 16, 1855 a mass meeting was held by blacks to demand voting rights, leading to Senate Bill 31 placing Negro male suffrage on the next ballot.

In the 1857 general election the measure was defeated by over 12,000 votes. A leader of the black community in Milwaukee, Ezekiel Gillespie, decided in 1865 to challenge the Elections Commission. He attempted to vote but was denied because he was black. He sued the board of elections in court and lost in Milwaukee Court but appealed to the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

On March 29, 1866 the court ruled that the 1849 election results had been valid and that blacks should have been given the right to vote since that time. On April 3, 1866 Ezekiel Gillespie cast the second ever vote by a black in Milwaukee, 31 years after Joe Oliver cast a ballot in the first election.

The challenges of voting for blacks have been consistently difficult. The 2016 presidential election loss by Hillary Clinton has been blamed on lower black voter turnout than in the previous two elections. It is true that there was a significant drop in black turnout in that election. The voter I.D. law passed by the Wisconsin legislature played a role in this lower turnout in Wisconsin.

Other factors that have negatively impacted black voting power include the gerrymandered state election maps that provided a tremendous edge for Republicans in state elections. Historically voting system changes such as run-off lections, at-large elections, felon disenfranchisement laws and voter purges have been used to lessen the power of blacks. From 2006-2008 Milwaukee County removed more than 34% of its voters from the rolls.

Voter I.D. laws passed prior to the 2016 election placed black and Latinos into a disadvantageous position. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported in 2016 that eligible black and Latino voters were 182% and 206% respectfully less likely than whites to possess an accepted form of state I.D. required to register. As a result 63,085 Milwaukee County eligible voters did not possess an accepted I.D. leading up to the 2016 election.

The Sentencing Project reported that felon disenfranchisement laws prevented 2.2 million blacks from voting (7.7% of black adults) by 2015. In Wisconsin it was worse. In our state 8.75% of blacks were ineligible to vote due to this law. The numbers were significantly higher in many Southern states. In Kentucky (26.15%), Virginia (21.9%), Florida (21.35%), and Tennessee (21.27%) of black adults were prevented from voting. This shift has taken place in concert with the growth of mass incarceration. Only 9 states disenfranchised at least 5 percent of their African American adult citizens in 1980, 23 states did so by 2015.

Many of Americans who’ve lost their right to vote have completed their prison sentences. In 2014 2.6 million disenfranchised persons had completed their sentences, comprising 45% of the total disenfranchised population. Only 1.17 million were disenfranchised in 1976 but 6.1 million were in 2016. 36% of those disenfranchised nationwide are black although we are just under 13 percent of all Americans.

Florida still disenfranchises nearly a half million blacks despite the ballot referendum giving felons voting rights back because the state legislature has forced them to pay all fines and penalties they owe before applying for reinstatement, recreating the poll tax in a new form. 2.2 million blacks are disenfranchised currently. Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Texas, Tennessee, Virginia and Florida all disenfranchise over 100,000 blacks each.

This level of black disenfranchisement impacted three swing states in the 2016 presidential election. In Florida Donald Trump won by 112,911 votes. 499,306 blacks are disenfranchised in Florida. If 23% of them could have voted, Hillary Clinton would have won the state. In Michigan Donald Trump won by 10,704 votes. 23,679 blacks are disenfranchised in Michigan. If 45% of them could have voted, Hillary Clinton would have won the state. In Wisconsin Donald Trump won by 22,748 votes. 22,447 blacks are disenfranchised in Wisconsin. If all of them could have voted the election would have been much closer.

Another important factor in the 2016 election are what are known as pivot counties. These are counties that voted for Obama in 2008 and 2012 and for Trump in 2016. Altogether, the nation had 206 Pivot Counties, with most being concentrated in upper Midwestern and Northeastern states. 11.1% of all Pivot Counties (1 in 9) nationally were in Wisconsin. Twenty-three of the seventy-two counties in the state were pivot counties. Blacks make up just 6.3% of the residents in Wisconsin. We are certainly important parts of the electorate. However when you look at those pivot counties most of them have very small numbers of black voters. The shift in those counties is the major reason Clinton lost Wisconsin.

One of the hidden impacts of partisan politics is the state of the U.S. Supreme Court. Since Eisenhower was president, 20 of the 28 persons nominated to the court have been by Republican presidents. In eight years Obama nominated 2 to the court but neither made it to the court. Trump placed two on the court in less than two years.

The court has consistently dismantled the power of the milestones of the 1960s Civil Rights campaigns. In 1978 the court established the “reverse discrimination doctrine” in the 1978 University of California v. Bakke case. The 1980 Mobile v. Bolden decision ruled intentional discrimination must be proven. Intent, not disproportionate impact is the bar for proving discrimination as a result.

A 1984 case, Holder v. Hall overturned a voter dilution decision of lower courts. During this case the only black currently on the court, Clarence Thomas, argued that Section 2 of Voting Rights Act should protect only an individual voter’s access to the ballot and not a minority group’s right to influence election results. Voter I.D. laws have been upheld by the court in cases from around the country. In 2008’s, Crawford v. Marion County Elections Board in Indiana the court ruled the voter I.D. law constitutional. They also upheld the strictest voter I.D. law in the country in 2014’s Texas Conference of NAACP Branches et al. v. Steen Decision and the Wisconsin voter I.D. law in 2015.

As I ponder the current state of black voting rights, I’m reminded that the challenges of the past have been replaced by challenges that are just as present as those from the past. We need to understand that we must follow the sage advice of Dr. King from many years ago.

“And so we shall have to do more than register and more than vote; we shall have to create leaders who embody virtues we can respect, who have moral and ethical principles we can applaud with enthusiasm.”