When Alexander Hamilton and the Marquis de Lafayette proclaimed “Immigrants, we get the job done,” the Milwaukee audience at “Hamilton: An American Musical” couldn’t wait for the end of the song to applaud and holler their affirmation. The song, “Yorktown (The World Turned Upside Down),” celebrates the rebellion’s defeat of the British troops, the end to tyranny, and the beginning of a new nation. And during a time when immigrants are being locked in detention centers by the thousands while the president continues to glibly announce his border wall plans, including a “beautiful wall” in Colorado, a simple line like this deserves applause. If the American revolutionaries had their King George, America in 2019 has its King Trump.

That one line aside, I confess that I had mixed feelings about attending the second night performance of Milwaukee’s Hamilton premiere. Of course, I had seen a few song on television, enough to know that this was a groundbreaking, energetic show. I even experienced mild FOMO (fear of missing out) every time a friend returned from a Chicago showing. I knew that it had won eleven Tony Awards in 2016, as well as a Grammy and Pulitzer Prize the same year. But that was the extent of it.

I admittedly could not tell anyone the first thing about either Hamilton or Burr, other than they had a duel – over something? which one died? So the weekend before the show, I brushed up on some history that I had not thought about for three decades.

Of course, I knew about the so-called “race blind” or “color conscious” casting. On the surface, I appreciated Lin-Manuel Miranda’s intentions to help audiences relate to and learn about the history of the Founding Fathers through faces and voices that reflect our country’s multicultural identities, and with music in familiar hip-hop, R&B, and pop styles.

I appreciated his gutsiness, how his musical had the potential of giving people of color ownership over the country’s history by giving actors of color most of the roles. The reversal of power could be powerful indeed. I read about how Miranda claims that “this is a story about America then, told by America now.” I got it. But something still didn’t seem right.

Is Hamilton the kind of play referred to by playwright August Wilson? He argued that “to mount an all-black production of a play conceived for white actors as an investigation of the human condition through the specifics of white culture is to deny us our own humanity, our own history, and the need to make our own investigation from the cultural ground on which we stand as black Americans.” Even though the multi-racial Miranda is not re-casting a play like “Death of a Salesman” with actors of color, is he running the same risk of denying people of color their own stories by simply substituting them into a story that has already been written – for real – by white people?

I am still thinking about it. We would have to be blind to imagine that people of color had any power in 1776, unconscious to pretend that people of color were among those “created equal” in the Declaration of Independence. But Miranda is neither blind nor unconscious. So what is he after? Is the historical fiction of Hamilton a revisionist history? From what I have read, Miranda has been praised for doing his homework as well as critiqued for taking poetic license in some instances. That seems fair for art. If it is revisionist, it is in the way the work is presented. Is it romanticized? Surely. What musical isn’t?

I get it: it’s good to see people of color in political roles that were never originally designed for them, in real life or musical life. It’s good to imagine an infant nation in which all immigrants were free to grow up to be “heroes” and “scholars” like Hamilton, even if they were “a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean by providence, impoverished, in squalor.” It’s good to honor a group of immigrants from Europe who fought tyranny and eventually created a new form of government. But does that mean turning another blind eye to the tyranny of that government over the indigenous people whose land they had conquered?

And don’t get me started on the ticket cost. Who is being left out of the Hamilton experience? It’s still hard for me to reconcile these complexities.

Perhaps that is because the American experiment is complex. In the musical, when Burr insists that the Constitution is a “mess” and “full of contradictions,” Hamilton agrees and adds, “So is independence. We have to start somewhere.” With almost two-and-a-half centuries to get independence right, we are still not there, though. In fact, the past three years seems to have reversed any progress.

Perhaps art has always allowed us to “start somewhere” new, to take poetic license with past and present realities and transform them with – in this case – riveting music, singing and dancing, to imagine a better future. To represent the unrepresented. To create a stage, a mental space, for us to move to the beatbox of a different drummer and reshape the narratives that need reshaping. To create, in this case, a cultural phenomenon and contribute to a necessary dialogue about the role of immigrants in the formation of this country and the role of each of us as activists. Miranda wants everyone in this historic moment to announce “I’m not throwing away my shot!”

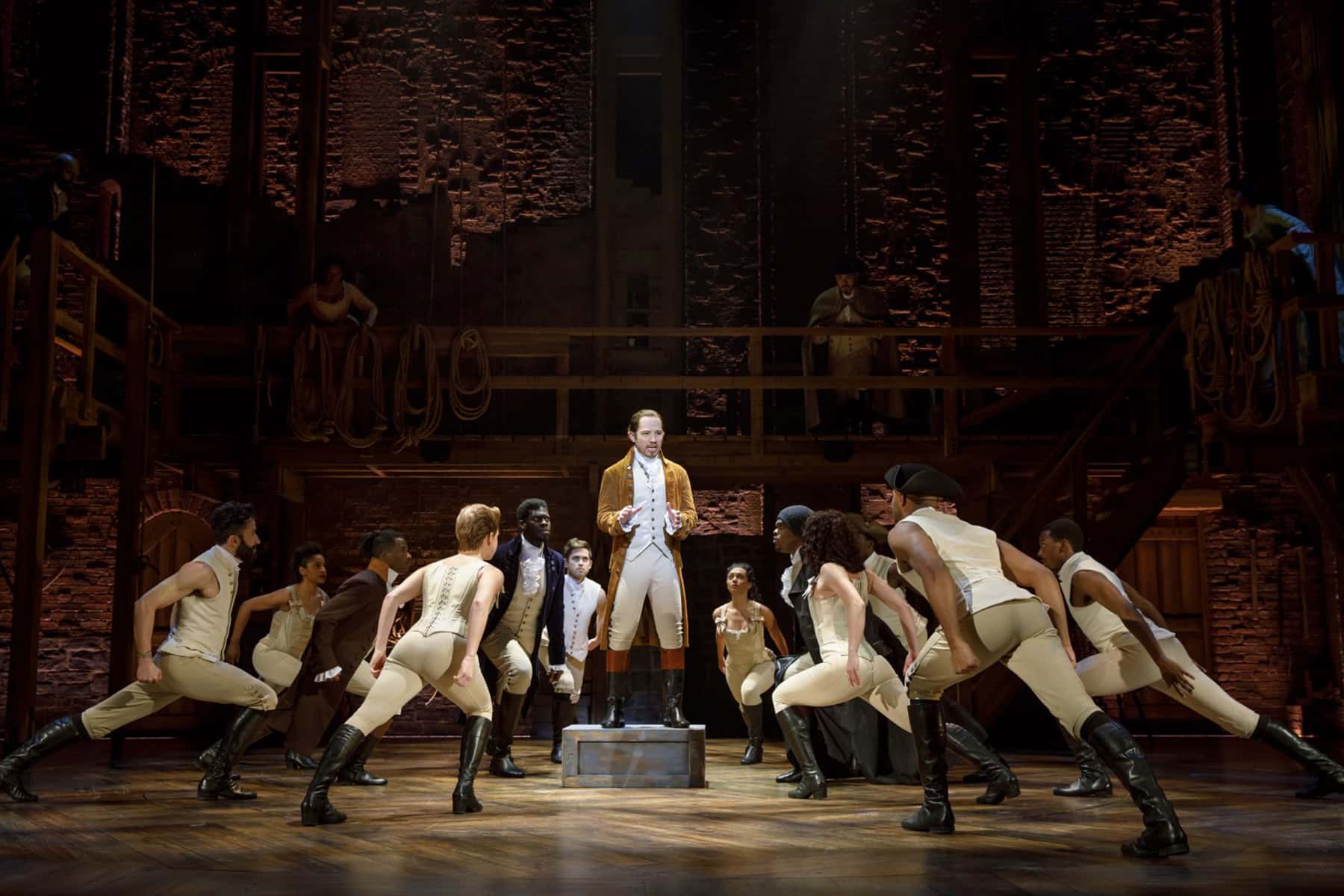

So when Daniel Breaker entered center stage to sing his first lines as Aaron Burr, what I was seeing was Miranda’s transformation of history, a better future, a new representation. The words rang true – pulled from the annals of history but set to a new beat – even though Burr’s skin color looked different. I think of similar transformations: of prolific painter Kehinde Wiley, who has reimagined Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon as a young African American man in bandana and fatigues and President Barack Obama, for his official portrait, sitting in his suit among flowering foliage. Of last year’s “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse,” which offered fans multiple dimensions of Spidey heroes, including the animated film’s teenaged hero Miles Morales, who is African American and Puerto Rican.

Joseph Morales, part Mexican, part Japanese, transformed his title role as Alexander Hamilton. Indian-American Shoba Narayan transformed Eliza Schuyler, Korean-American Marcus Choi transformed George Washington. The only major character played by a white actor is Evan Morton’s King George. Yes, I get it.

I was not actually watching history, I was watching a hoped-for American future, a 2021 without King Trump. I can hear the optimism of the Schuyler sisters even in the midst of such revolutionary risk: “Look around, look around at how lucky we are to be alive right now!”

Miranda’s Hamilton was challenging me to be my own Hamilton, a “self-starter” with a “just you wait” mindset instead of a complacent Burr, who tells Hamilton: “Good luck with that: you’re takin’ a stand. You spit. I’mma sit. We’ll see where we land.” I need, we need, to write and act like we are “running out of time.”

I am not done thinking about the complexities and contradictions of this musical. I am still wrestling with August Wilson’s words and how they do or do not apply to Hamilton. I am thankful, however, that I was privileged to see it and that I am free to think about it. Thank you, Lin-Manuel Miranda, for taking an imperfect shot with your art. If I might be so bold, I think I disagree with you when you say that “this is a story about America then, told by America now.”

If anything, Hamilton is a story about America in the present and an American future, told through the lens of America then. Like Hamilton, you’re “thinkin’ past tomorrow” and inviting us to sing and dance with you to make new revolutions happen.