“Don’t say, ‘Yeah’ to me: I’ll blow your head off. Get your clothes on.”

– Roy Milam, describing what he said prior to murdering Emmett Till, in an interview with “Look Magazine”

“There are no good times to be black in America, but sometimes are worse than others.”

– David Bradley

Emmett Till was 14-years old when he was kidnapped thirty-seven miles from my hometown in Mississippi in 1955 and eventually murdered. He would have been 78 years old on July 25th had he not been murdered after a white woman made false accusations against him in Money, Mississippi.

Three students at the University of Mississippi (Ole Miss) have recently been suspended from their fraternity after an Instagram post featured them posing with a shotgun and AR-15 assault rifle in front of a bullet mocked memorial to Till.

Being a native of Mississippi, my home state is often an embarrassment to me. Racism is alive and well and very prevalent in Mississippi decades after the end of the Civil Rights Movement. I rarely travel back “down south,” as I did regularly when I was younger. Many years ago I decided to travel to Money, Mississippi and inquire about the Till case. My family told me to reconsider, that I was risking my life by doing so. I listened to them and decided not to go. I still regret the decision to this day.

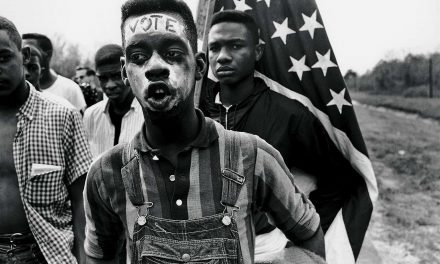

I was born in a state that had some of the most violent racism in the nation. Dr. King marched through my hometown during the campaign to register black voters. Each time I travel home I see the tall Confederate soldier memorial erected next to the courthouse. It stands tall and is a testament to the memory of the Confederate States of America. Most Americans know little to nothing about the history of the Confederacy, and most of what they believe is based on a false narrative known as the “Myth of the Lost Cause.”

Confederate Major General Patrick Cleburne complained at the end of the war that, “the history of this heroic struggle will be written by the enemy; that our youth will be trained by Northern school teachers; will learn from Northern school books their version of the war.” Historian Edward H. Bonekemper III wrote that “it did not work out quite that way” in his book “The Myth of the Lost Cause.” The South lost the war but eventually won the narrative of how the war was fought.

Mississippi was one of 15 states where slavery was still legal in 1861. Eleven of these states broke away from the United States to form a new nation. They called it the Confederate States of America. It was modeled after the “Republic” they had severed ties with. The Confederate Constitution mirrored the U.S. Constitution with one major difference. The words “slave” and “slavery” did not show up in the U.S. Constitution until the Thirteenth Amendment on December 18, 1865, months after the major fighting of the Civil War ended. The Confederate states decided to call the millions of enslaved blacks what they saw them as, slaves. The word was used throughout their constitution.

The U.S. Founding Fathers were too ashamed in 1787 to call the more than 600,000 enslaved Africans “slaves.” They used vague language to get around using the word “slave.” They called my ancestors “other persons” when they knew very well that they were enslaving them. About half of the signers of the Declaration of Independence that proclaimed “all men are created equal” were slaveholders. Thomas Jefferson and George Washington both owned hundreds of men, women, and children.

As the northern states gradually abolished slavery by law, the “peculiar institution” continued to grow in importance. All of the original thirteen colonies enslaved Africans at some point. Slavery lasted significantly longer in the North than it did in the South. Most of us have learned to think of slavery as a Southern institution because that was what we learned in school. But, the North has blood on its hands as well. Even those territories that never officially recognized slavery in their laws, allowed whites to enslave Africans and Native Americans.

Contrary to what was taught in school, states rights was not the cause of the Civil War. Mississippi and the other states that fought against the Union Army clearly spelled out that they were seceding from the Union to protect slavery, leading to the deadliest war in the nation’s history. Mississippi became the second state to leave on January 9, 1861, following the lead of South Carolina less than a month earlier on December 20,1860. In its letter of secession, Mississippi explained its reasons for leaving the United States.

“Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product, which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth… we do not overstate the dangers to our institution… we resolve to maintain our rights with the full consciousness of the justice of our course, and the undoubting belief of our ability to maintain it.”

The war was also about hearts and minds. Whites in the North and South had been conditioned for generations that they were superior to blacks. Far too many still believe this to be true. It is not just the clearly racist folk that marched in Charlottesville a couple of years ago. We saw them because they wanted to be seen. It is the silent racists who are more dangerous. Some of these are people who clearly benefit from the inequality that negatively impacts the lives of the 39 percent of the nation that is not white. They are silently protecting the status quo.

In 1860, 49 percent of families in Mississippi owned African people. No other state had a higher percentage. 436,631 Africans were enslaved in a state that had only 791,305 people. 30,943 individuals were listed in the 1860 census as slaveholders in Mississippi. One of these, a man named Dempsey Diltz, owned my family in Yalobusha County Mississippi.

After WWII, black veterans came back from fighting for democracy and defeating fascism, expecting to enjoy the freedoms they fought for. Mississippi was not about to grant them this freedom or respect their sacrifices.

“This [second world] war was not fought to change one whit the definition or meaning of true democracy and true Americanism. We fought to preserve what we already had. If some overzealous person or persons left colored Americans under the impression that a victory in this recent war meant the breaking down of the color line in the South or social equality and intermarriage with the white race, then I am sorry.”

– United State Senator Theodore G. Bilbo

Emmett Till was one of three blacks lynched in Mississippi in 1955. Mississippi lynched 539 blacks between 1882 and 1968, according to records kept by the Tuskegee Institute. No state lynched as many as them, and only Georgia at 492 approached the brutality of Mississippi. These numbers represent only the documented lynchings that occurred. Many went unreported. Although unreported, those blacks that “were disappeared” as blacks spoke of them, were never forgotten by their families and friends.

Large violent mobs of whites, which sprang up throughout the South to terrorize blacks, led to the largest voluntary migration of people in American history. The Great Migration saw over six million blacks leave the South from the early 1900s through 1970. They fled the violence, degradation, low pay, and segregation of the South.

The narrative about states rights being the cause of the Civil War began years after the war ended and has been perpetuated by historians who knew better for well over a century. Confederate Generals Jubal Early and William Nelson Pendleton created the myth of the why the war was fought and lost by the South beginning in the 1870s.

Likewise the myth of the Great Migration being primarily about job opportunities has been sold to us for decades. Blacks were fleeing for their lives. I have heard several personal stories of black men who had to sneak out of the South under the cover of darkness or be murdered. The South was not a safe place to be black, and Mississippi was known by many to be the most dangerous state to live in if you were black. This reputation was well deserved and bragged about by whites in the state.

From 1882 until 1968, nearly 3,500 blacks were lynched, most of them in the Southern states. 1947 marked the 65th consecutive year that a lynching was recorded. 231 lynchings were recorded in 1892, the largest for any year. From 1882 until the turn of the century, about 150 lynchings occurred per year. Most lynching victims had been accused of murder or attempted murder, not rape, as many believe. A 1940 study by Arthur Raper showed that at least one-third of victims were falsely accused, as was the case for Emmett Till.

Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milam were tried for the murder of Till. They had kidnapped Till, brutally beat him, shot him in the head, and tied a cotton gin fan to his body with barbed wire to weigh it down in the Tallahatchie River. His corpse floated to the surface and was found by a fisherman. The city of Sumner, one of two county seats in Tallahatchie County, was the scene of this farce of a trial. The courtroom was segregated with blacks being forced to sit in the back and black reporters being forced to sit at a card table off to the side of the courtroom.

His murderers were tried in a Tallahatchie County “kangaroo court” and found not guilty by an all-white, all-male jury that deliberated 67 minutes which included a lunch break. One of the jurors joked that “we wouldn’t have taken so long if we hadn’t stopped to drink pop.” Milam and Bryant lit up cigars and kissed their wives in celebration after the verdict was read.

“Wasn’t it just like a nigger, to try and cross the Tallahatchie River with a gin fan around his neck.”

– A joke heard during the trial

The open casket funeral of Till in his home of Chicago galvanized the black community and is considered by some to be the spark for the Civil Rights Movement. His mother Mamie Till said she demanded an open casket funeral so that the world could see “what they did to my boy.”

Bryant and Milam confessed to “Look Magazine” knowing they could not be tried again due to double jeopardy laws. In the interview they described the brutal beating and pistol-whipping that Till endured before being shot at point-blank range. They stole a cotton gin fan and tied barbed wire around it while wrapping Till’s body up, preparing to toss it in the Tallahatchie River after driving nearly 75 miles to find a perfect spot. They wondered aloud if they would get in trouble for stealing the fan. According to their memory, Till never cried or “hollered.”

“I never hurt a nigger in my life. I like niggers – in their place – I know how to work ’em. But I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it, niggers are gonna stay in their place. Niggers ain’t gonna vote where I live. If they did, they’d control the government. They ain’t gonna go to school with my kids. And when a nigger gets close to mentioning sex with a white woman, he’s tired o’ livin’. I’m likely to kill him. Me and my folks fought for this country, and we got some rights. I stood there in that shed and listened to that nigger throw that poison at me, and I just made up my mind.”

– J. W. Milam

It was years later, prior to dying, that Carolyn Bryant admitted to an author of a book about the murder that she fabricated the story of the flirting and dog whistle that led to Till’s murder. No one has ever been held accountable for the murder.

The memorial to Till erected near the spot he was thrown in the Tallahatchie River has been damaged and vandalized multiple times since it was first erected in 2008. Vandals first threw the sign in the river. The replacement was riddled with over 300 bullets or shotgun pellets. The sign that the three students recently posed in front of had at least 10 bullet holes in it before being removed. There are plans to replace it with a bulletproof sign soon.

As the city of Milwaukee prepares to erect a memorial to George Marshall Clark, a black man lynched on the corner of Water and Buffalo streets in 1861, I hope that people here do not disrespect it in any way similar to what Mississippians have done to the Till memorial.

The 54th anniversary of Till’s murder will be on August 28. The current state of race relations shows us that we have made much less progress since his death than we like to credit ourselves with. Laws have changed and blatant acts of virulent racism are less common than they once were. However, as Mississippians can attest, hearts and minds have not changed all that much.

Mississippi is still a scary place for blacks to reside. They live in the shadow of the Confederacy, which remains alive and well 154 years after the Army of Northern Virginia led by Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee, the second-largest Confederate army after Lee’s with over 90,000 troops, did not officially surrender until April 26, 1865.

The Confederate government never surrendered and no treaty was signed to end the war. It was over a year later on August 20, 1866 when President Andrew Johnson declared the war formally over.

“said insurrection is at an end and that peace, order, tranquility, and civil authority now exist in and throughout the whole United States of America.”

For blacks in Mississippi and elsewhere, the words rung hollow. It is clear to me that the Civil War is still being fought today. It was a battle in the race war we have been fighting in this country for many years. This race war began with the arrival of the first Pilgrims landing on Plymouth Rock in 1607.

The latest act of vandalism with Emmett Till’s memorial confirms that many in the country do not believe the race war is over. We are approaching a tipping point where an explosion is bound to happen as a result of the polarization of levels not seen since the Civil Rights years. When the rhetoric coming from the White House continues to inflame tensions there is no way to predict the outcome.

“This is a war within our family of nations, a war which will reduce the strength and destroy the treasures of the white race.”

– Charles A. Lindbergh in Aviation, Geography, and Race, “Reader’s Digest,” November 1939

© Photo

Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and Emmett Till Interpretive Center