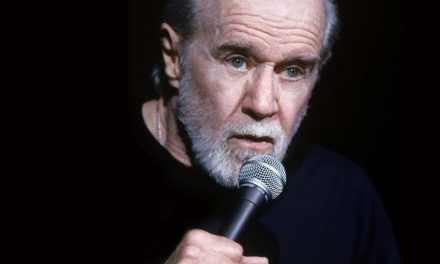

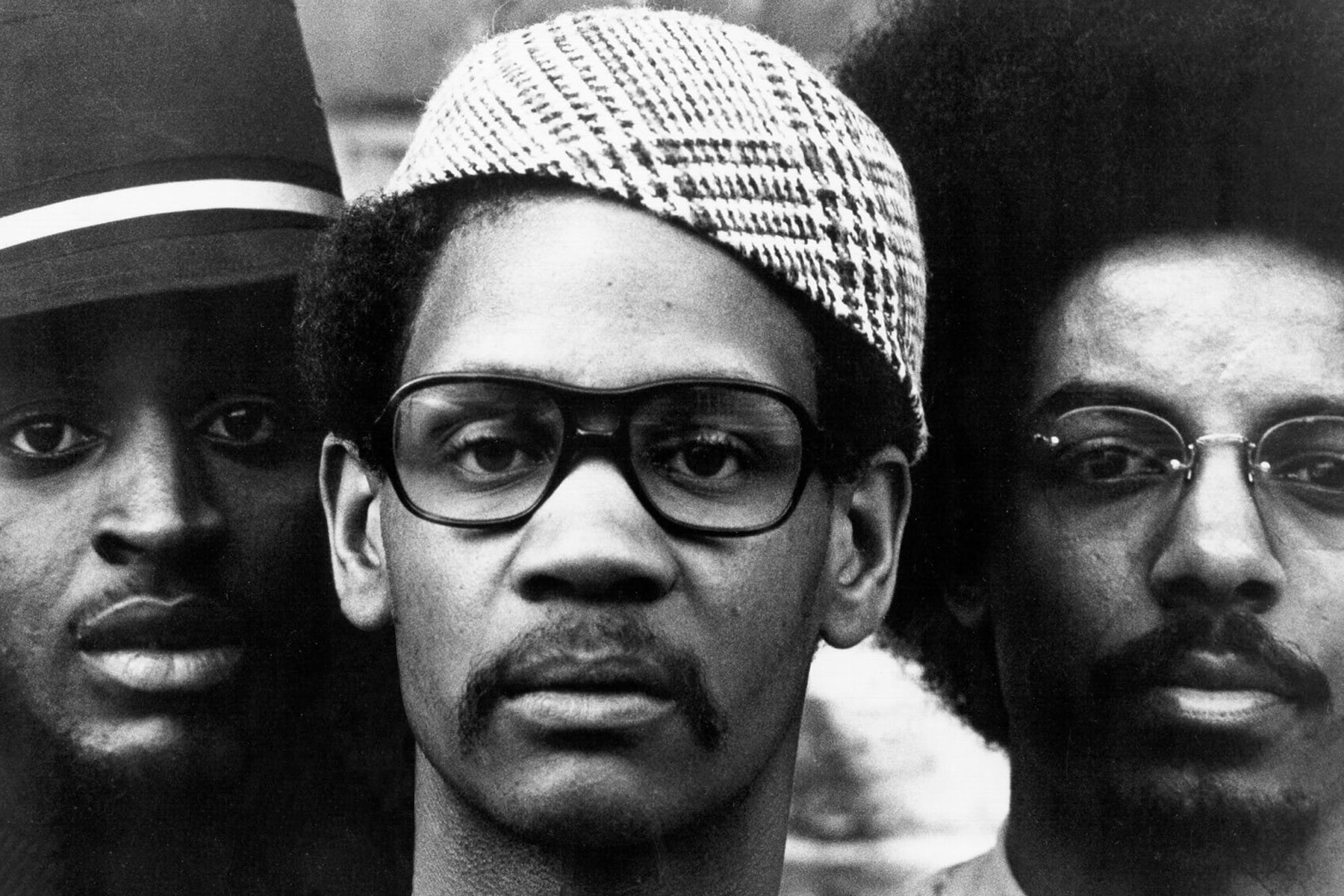

It is half a century since the Last Poets stood in Harlem, uttered their first words in public, and created the blueprint for hip-hop. At an intimate open house session, they explain why their revolutionary words are still needed.

You can trace the birth of hip-hop to the summer of 1973 when Kool Herc DJ’d the first extended breakbeat, much to the thrill of the dancers at a South Bronx block party. You can trace its conception, however, to five years earlier – 19 May 1968, 50 years ago this weekend – when the founding members of the Last Poets stood together in Mount Morris park – now Marcus Garvey park – in Harlem and uttered their first poems in public.

They commemorated what would have been the 43rd birthday of Malcolm X, who had been slain three years earlier. Not two months had passed since the assassination of Martin Luther King. “Growing up, I was scheduled to be a nice little colored guy. I was liked by everybody,” says the Last Poets’ Abiodun Oyewole. He was 18 and in college when he heard the news. “But when they kiIIed Dr King, all bets were off.”

That day led to the Last Poets’ revelatory, self-titled 1970 debut of vitriolic black power poems spoken over the beat of a congo drum. Half a century later, the slaughter continues daily, in the form of assaults, school shootings and excessive police force.

“America is a tеrrоrist, kіІІіng the natives of the land / America is a tеrrоrist, with a slave system in place,” Oyewole declares on the Last Poets’ new album, Understand What Black Is, in which he and Umar Bin Hassan trade poems over reggae orchestration, horns, drums and flute. It’s their first album in 20 years, reminding a new generation of hip-hop’s roots in protest poetry.

“Ghostface Killah and RZA [from the Wu-Tang Clan] will bow down when they see us,” Oyewole says. “People say we started rap and hip-hop, but what we really got going is poetry. We put poetry on blast.” The Last Poets’ poems have been sampled or quoted by NWA, A Tribe Called Quest, Public Enemy and many more; the rapper Common’s Grammy-nominated 2005 song The Corner features the Last Poets (as well as Kanye West) representing the old-school guys in the neighbourhood who explain how black power rose up from the streets. “The corner was our Rock of Gibraltar,” Bin Hassan says in the song. “Power to the people!”

The late Gil Scott-Heron, meanwhile, is often mistakenly believed to have been a member of the Last Poets. Rather, they were contemporaries, the connective tissue between the rap, hip-hop and spoken word genres they helped inspire, and their own direct influences: jazz and Langston Hughes and the words of their slain leaders. “‘I been to the mountaintop!’” Oyewole says, quoting King’s final speech when I visit him. “Ain’t nothing but a poem.”

On this Sunday, as with almost every Sunday for the last three decades, Oyewole is hosting the Open House poetry workshop in his Harlem apartment, a 20-minute walk from the spot where the Last Poets once spoke their first words. The door is cracked open for the stream of visitors who will fill the seats all afternoon and evening.

Oyewole rarely reads his own work, but instead serves as teacher, leader and cook (“I do this to repair myself,” he says). There are homemade salmon croquettes, shrimp grits and potatoes waiting in the kitchen. Fifty years of vintage posters and framed awards adorn the walls in the corridor – a literal hall of fame – while others are covered with masks from Oyewole’s travels all over Africa and South America.

When he was growing up, Oyewole says, his father “raised me to hard work” – weeding the garden in Jamaica, Queens – “and I got love overtime from my mother”. He calls two women mother, including the aunt who raised him and demanded he learn to clearly recite the Lord’s Prayer so she could hear every word in the kitchen.

Now 70, wiry, energetic, and having received his chosen name in a Yoruba religious service, Oyewole still uses his voice like an instrument, dramatically dialling it up and down in volume for emphasis in the free-ranging conversations that take place in his living room: basketball, the novels of Chinua Achebe, the backlash election of Donald Trump. “All Barack Obama got to do was clean up the mess made by the Bush administration. Pride was restored, money was restored. But that’s all black folks has ever done, cleaning up. We’ve been the biggest servants this country has ever seen.”

In the early 70s, when the Last Poets’ first album began to attain popularity, Oyewole was in prison. He had been studying at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, and robbed a local Ku Klux Klan meeting. “I have a strong distaste for guns now,” he says. “But back then I treated my .38 Special like it was my wallet.” During his three-and-a-half-year sentence, Oyewole’s good behaviour permitted him study leave. On school days, as part of his study, he would visit a radio station and read out entire books on the air, which were then broadcast in the evenings. “I’d come back to my cell after class and guys would holler: ‘I got you on my headphones, New York!’” he says. These days, when he teaches poetry workshops to teenage girls incarcerated at Rikers Island, he exhorts his students to educate themselves. “I tell them: you put a top hat on time and you learn how to get time to serve you!”

Last Poets drummer Baba Donn Babatunde drops by and Oyewole introduces him as the heartbeat of the group. Impressively tall, he wears a gold pendant on his dress shirt in place of a tie and speaks in a serious, mellifluous baritone. When he was 11, his activist mother turned him on to the Last Poets; since 1991, when he joined the group that so inspired him, he tries to summon in his drumming “the spirit, the anger I felt when I first heard those poems. What I do is the dramatisation of those words, carrying them rather than fighting them.”

By and by others drift in. “Can I play your drum?” a guy called Jason asks as he wanders in. In his early 20s, he smokes some dope and grows quickly impatient. “Check this out!” Jason pleads, pausing to cue up a phone recording of himself playing at home.

Oyewole isn’t having it. “I don’t want to hear your damn gadget!” he explodes. He refuses to use a mobile phone. “In 1972, in my poem Mean Machine, I wrote: ‘Synthetic genetics controls your soul,’” he says. “Who would I be if I had one of those things now? Some of them here get up and read their poetry right off their gadgets. I tell them: that thing is a wall between us and you.”

He is equally harsh on those who blame their circumstances for their troubles, a philosophy Bin Hassan shares. One of Bin Hassan’s poems on the new record, North East West South, is a moving response to the death of Prince, who was a fan of the group. “I grew up black in the midwest; I had a creative father who could be abusive,” Bin Hassan says a few days after the workshop. “The kid in Purple Rain is named Jerome, and that’s my real name. So when I saw the film, I felt like it was my life story, too. But you can’t get hung up – you have to use that and move on.” Bin Hassan moved to Baltimore several years ago and, in between writing poems, he looks after his grandchildren. “I cleaned up,” Bin Hassan says, having fought a crack addiction, “and I’m thankful I’m still here.”

Rain Maker, a 20-year veteran of the workshop, runs through poems for a gig in Albany the next night. Albe Daniel, an actor and poet who calls Oyewole a surrogate father and addresses him as “Pops”, brings his daughter Katie, six. A poet called Miriam strides up to Oyewole’s chair: “This is Ramesses!” she says proudly, and a tiny face peeps out from a carriage. “Well, well,” says Oyewole, smiling. “I just got off the phone with my own son, Pharaoh.” A guy who introduces himself simply as Born brings bags of wine and groceries; soon there’s frying in the kitchen, Lauryn Hill on a mini-stereo by the stove, the happy chaos of a little party in the making.

At about 8pm, Oyewole shuts everyone up. “We’re getting ready to do poetry!” he shouts and everyone dutifully lines up. Immediately, a chorus of 15 or so voices – young and old, all persons of colour – recites in bright, powerful unison: “I want to be who I want to be …” This is the “pledge”, committed to memory by every workshop poet, written on the fly by Oyewole years ago when he was doing a school visit in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant district and a sharp-eyed student noticed he hadn’t recited the US pledge of allegiance. “I don’t sing no Star-Spangled Banner – that’s a war song!” he responded. “And I tell you what, I got a better pledge than that one.”

“I want to feel good about me, and blame no one for my misery,” the poets continue in collective, syncopated rhythm. “I want to say what I know, to make my brothers and sisters grow.”

“Baby, that’s a mouthful!” Oyewole says, his eyes lighting up. It’s time for the workshop participants to step up.

A guy in his 20s rises, mumbles his name inaudibly. He recites his poem over familiar music, the instrumental of Childish Gambino’s Redbone. “You got a flow,” Oyewole acknowledges, “but I want to see you being totally original.”

A discussion about artistic theft ensues. One of the best-known homages to the Last Poets arrived via Notorious BIG’s debut single, Party and Bullshit. Recently, a judge dismissed a lawsuit in which Oyewole alleged that Biggie, Rita Ora and other artists, infringed on copyright and used the lyrics in a “non-conscious” way, corrupting the original message.

“When the revolution comes, some of us will probably catch it on TV, with chicken hanging from our mouths,” the Last Poets chant on their debut. “When the revolution comes …!” The line in question is one they say in a rhythmic chorus: “But until then you know and I know niggers will party and bullshit, and party and bullshit …” The rhythm is echoed in Biggie’s recitation of the line. “It’s like prophecy, Pops!” Albe Daniels says. “Y’all called it. The revolution came and they were all partying and buIIshіttіng.”

Vanessa, a New York-raised teacher in her early 40s with family back in Haiti, waits through a few protracted rounds of talk before the room shushes again. “May the dust of your slain sisters stick to the soles of your feet when you walk,” she reads midway through her poem and Oyewole stops her. “Do that line again!” he shouts appreciatively. “That was so f*ckіng powerful.”

At midnight, the open house is closed. “I tell them all to scatter like mice!” Oyewole says. At seven the next morning, like every morning till 12.30pm, he will return to his desk and write facing east, to Marcus Garvey park. “I look east because that’s where the sun rises,” Oyewole says. “That’s where life begins.”

Rebecca Bengal

Michael Ochs Archives

Originally published on The Guardian as The Last Poets: the hip-hop forefathers who gave black America its voice

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.