While Wisconsin’s unemployment rate hovers near historic lows, one Milwaukee neighborhood’s chronic economic misery continues to weigh heavily on the prospects of thousands of its residents.

The 53206 zip code on Milwaukee’s north side embodies the kinds of longstanding problems that can plague disadvantaged urban communities: acute poverty, high unemployment, mass incarceration, a dearth of local jobs and little room for economic mobility. The neighborhood’s troubles have drawn increasing attention in recent years, and a 2016 documentary explored how high incarceration rates in the zip code affect the lives of its residents.

One important issue contributing to and compounding 53206 residents’ woes is a lack of transportation options from the urban center to the suburbs, where the metro area’s job growth has been centered for decades.

The lack of economic mobility in the neighborhood “is astounding,” said Marc Levine, senior fellow and founding director of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Center for Economic Development and the author of a March 2019 study describing the stagnant economic prospects of those residing in 53206. Residents of the zip code are 95 percent African American, and its poverty rate in 2017 was 42.2 percent, which is six times greater than in the Milwaukee suburbs.

“There are multiple disadvantages piled on top of one another that are concentrated into this rather tight geographic space,” Levine said in a March 15 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now.

“That, as we document in the study, creates not only immediate problems … but long-term problems in terms of the ability of people living in the neighborhood to achieve the American dream of economic opportunity.”

Levine noted some improving economic indicators in the neighborhood over the decade since the depths of the Great Recession — employment among working age men has jumped nearly 27 percent — but 53206 remains a zip code of deeply concentrated disadvantage. The situation is such that Levine described the local circumstances as a chronic “stealth depression.” Indeed, more than half of all working age men in 53206 remain unemployed.

A number of factors have contributed to the neighborhood’s depression, Levine told WisContext in a follow-up interview, including entrenched racial segregation and discrimination. One key factor is a longstanding dearth of local job opportunities, Levine said. On top of that, the jobs that are available in and around the zip code are often low-paying. Nearly 10 percent of adults in 53206 who have full-time, year-round employment reported income below the poverty level, he found.

The local job market is so broken, Levine added, that even classic routes toward upward economic mobility, including educational attainment, are limited.

“Economists have well documented an educational premium for employment and earnings,” Levine said. “More education equals better employment.”

While that relationship holds true to a degree for residents of 53206, with college graduates earning more than high school graduates, who earn more than those who didn’t complete high school, Levine found that a college graduate in the zip code earns roughly the same income as someone in suburban Milwaukee who did not complete high school.

“The lowest level of education attainment in Waukesha County provides an essentially comparable economic well-being as a college education in 53206,” Levine said. “That’s startling and shows that place matters” for job prospects.

Underlining the role of geography in delineating the fate of economically depressed urban neighborhoods is the fact that net local job growth in the last 20 years has been concentrated largely in the suburbs surrounding Milwaukee.

“There’s simply greater job growth in the exurban ring,” Levine said.

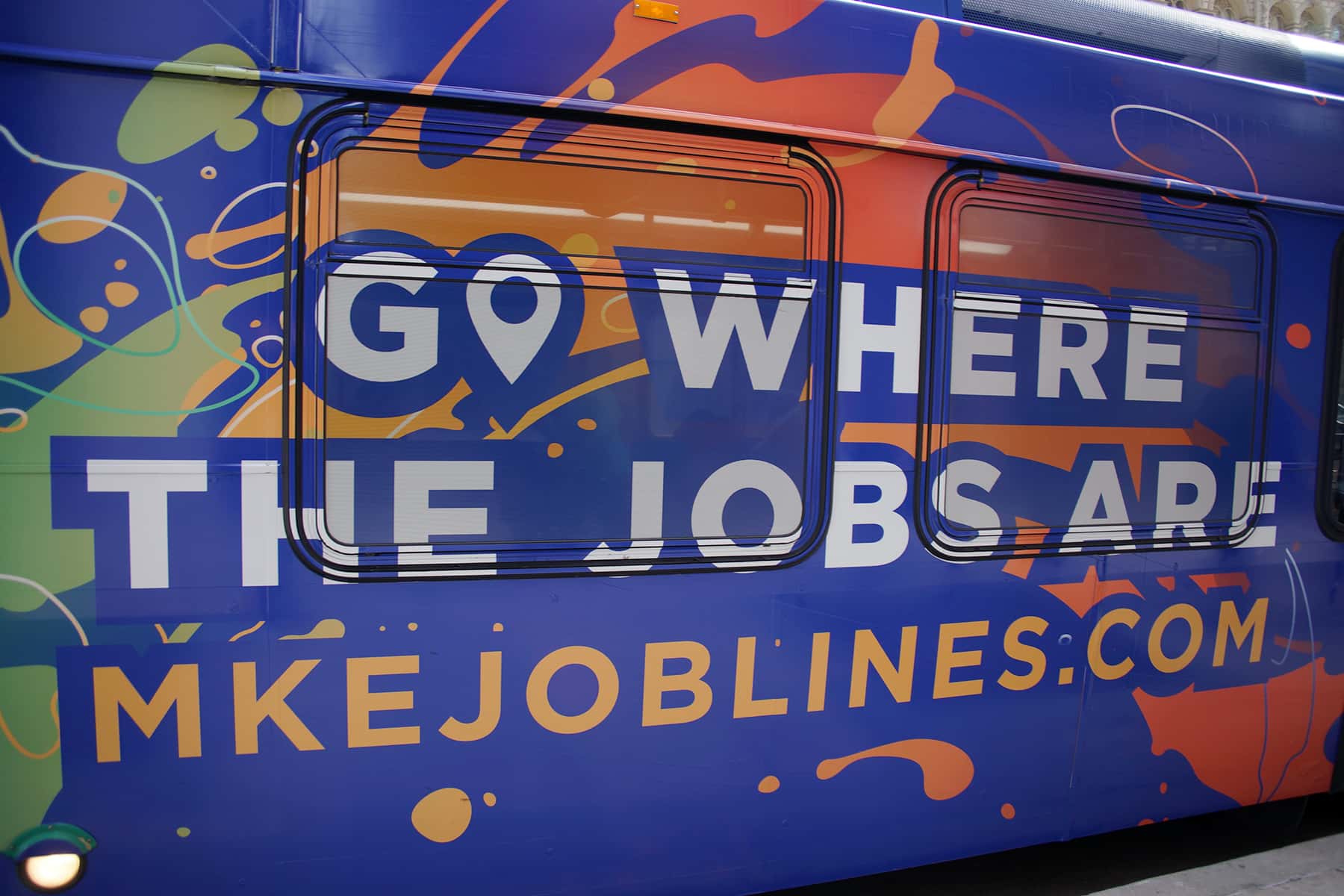

Those jobs can be difficult to reach for residents who can’t afford to drive themselves and who rely on public transportation, he explained. An October 2018 study put out by the Center for Economic Development found a “pressing need” for expanding Milwaukee County Transit System bus routes between the urban and suburban job centers. Two such routes, branded JobLines, began in 2014 with temporary funding that ran out at the end of 2018.

Both those routes have since been discontinued, with another route between the downtown Milwaukee Intermodal Station and the northwestern suburb Germantown picking up some of the slack. Milwaukee County is funding that route temporarily until August 2019, and JobLines advocates are hoping to secure funding to maintain and expand the connections. It takes roughly 25 minutes to reach the Intermodal station from the 53206 neighborhood by bus.

“The region will not prosper as long as large areas of Milwaukee remain impoverished, cut off from areas where job growth is occurring,” wrote the author of the transportation study, Joel Rast, who is the current director of UW-Milwaukee’s Center for Economic Development. “Employers outside Milwaukee County will continue to face significant worker shortages if ways are not found to connect job-seeking Milwaukee residents with the positions these businesses seek to fill.”

Lester Williams chairs the transportation task force for Milwaukee Inner-City Congregations Allied for Hope, or MICAH. He grew up in the 53206 zip code, and still lives nearby.

Williams said one of the discontinued JobLines routes made it possible for him to travel from his home in Milwaukee to a job in New Berlin. He’s now employed elsewhere, but Williams and his partners at MICAH are working to secure funding to maintain and expand public transportation between Milwaukee’s urban core and suburban job centers.

“You have all these outer areas that have industrial parks where there are so many companies that are really looking for entry-level employees,” Williams said. “Well 53206 and other areas have people who want jobs, but there’s not enough funding for people to get out to these jobs and they’re cutting the bus lines. The jobs are out there, but there’s no way for people to get to work.”

Milwaukee County Transit System and Lee Matz

Originally published on WisContext.org, which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.