By Dwight Stirling, Lecturer in Law, University of Southern California

As a military organization divided into 50 distinct parts that can be commanded by either the president or state governors, the National Guard is perhaps the least understood branch of the U.S. armed forces.

Despite its complexity – or perhaps because of it – the National Guard is taking the lead role in the military’s response to the coronavirus outbreak crisis. As many as 10,000 National Guard members have already been activated to help communities around the country, with many more expecting a call-up soon. People may know, from TV ads or other brief appearances in the media, that National Guard members are part-time citizen-soldiers, but not much else. As a longtime National Guard attorney and military law professor, I can explain a bit more about how the National Guard works.

Who are they?

There are nearly 450,000 National Guard personnel spread out throughout the 50 states and various territories. The size of each state’s National Guard is roughly proportional to its population. A large state like California has about 22,000 members, while smaller states such as Vermont have about 3,000.

So-called “weekend warriors,” in normal circumstances Guard members perform two days of training per month and two full weeks in the summer. Meeting at local armories, they brush up on their military skills while practicing how to respond to real-life calamities. The Guard’s motto captures the idea: “Always Ready, Always There.”

When not training, members of the Guard are indistinguishable from the general population. Many hold civilian jobs at places like Costco, Bank of America and the Los Angeles Police Department. A large number are full-time students looking for college money and vocational skills that they can get while serving. Still others are former active duty service members who want to continue serving on a part-time basis.

Who issues the orders?

National Guard members are most often called to service under the leadership of their state governments, as has already happened in New York and California, among other places. Those National Guard troops answer to the governor of their state. Every state in the union has a National Guard organization, which legally operates “under state authority and control.” The guard’s job is to protect the civilian population during large-scale emergencies, serving as backup for overwhelmed firefighters, police officers and other first responders.

State National Guard units are the modern-day descendants of state militias, the centuries-old military bodies that pre-dated the signing of the Constitution. Guard members embody the concept of a citizen army, tracing their lineage dating directly to the Minutemen of Lexington and Concord. The very existence of a state-specific military force answering to the governor reflects the power of state sovereignty as well as an enduring distrust of federal authority.

Controlled by governors and regulated by state legislatures, the legal status of National Guard personnel is unambiguous: “National Guard personnel who have not been called to active federal duty are considered employees of the state in which they serve,” explained a California appellate court.

When in a state status, Guard members have virtually no limits on the assistance they can provide civil authorities. They can build roads, airdrop food supplies and operate medical facilities. They can even perform traditional police activities if there is large-scale unrest.

In very rare instances, the National Guard can be what is called “federalized” and put under the command of the regular full-time military. This happened most recently in response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Other examples include the response to the Los Angeles riots in 1992 and enforcing the integration of Alabama schools in the early 1960s.

That’s unlikely to happen in the coronavirus response because it can be less effective than preserving state control and imposes strict limits on what guard members can do.

Who foots the bill?

National Guard uniforms say “U.S. Army” or “U.S. Air Force,” but state guard members do not fall within the president’s chain of command. In fact, as my own analysis shows, National Guard personnel may legally disregard presidential instructions; they answer only to their respective governor.

That said, the president controls when federal money gets spent on guard activities. While the Department of Defense pays for the Guard’s monthly training sessions, it has no obligation to pay for gubernatorial call-ups. Whether a president opens up federal spending has a large influence on whether, and when, governors activate their National Guard units in the face of an emergency.

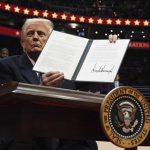

That is why President Donald Trump’s recent decision to pay for 100% of the activation costs for three states’ National Guard units is of particular significance. Without this action, governors would be forced to use state funds to cover millions of dollars in extra expenses.

Trump’s claim to have “activated” the national guards of California, New York and Washington, however, is not true. Only the governors can do that, but his commitment to pick up the tab no doubt makes the decision easier for cash-strapped states that may be worried about how they would pay the costs. Other states may well seek federal support for calling up their National Guard units as the crisis spreads.

Originally published on The Conversation as National Guard joins the coronavirus response – 3 questions answered

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.