Martin Luther King Jr. is useful to just about everyone nowadays. For President Donald Trump, celebrating King is a chance to tell everyone that he shares “his dream of equality, freedom, justice, and peace.” For Ram trucks, it’s a chance to, well, sell trucks.

This was not always the case. In 1983, 15 years after King’s death, 22 senators voted against an official holiday honoring him on the third Monday in January. The North Carolina senator Jesse Helms undertook a 16-day filibuster of the bill, claiming that King’s “action-oriented Marxism” was “not compatible with the concepts of this country.” He was joined in his opposition by Senators John McCain, Orrin Hatch and Chuck Grassley, among others.

Reagan reluctantly signed the legislation, all the while grumbling that he would have preferred “a day similar to Lincoln’s birthday, which is not technically a national holiday.”

And guess what? He had a reason to be hesitant. The real Martin Luther King Jr. stood for a radical vision of equality, justice and anti-militarism that rebelled against Reagan’s entire agenda. Today more than ever, we need to rediscover that champion of working people.

The Disneyified version of Dr. King begins and ends with his role as a civil rights leader, who summoned Christian teachings, as well as Gandhian tactics, and told us of his dream that “one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.’”

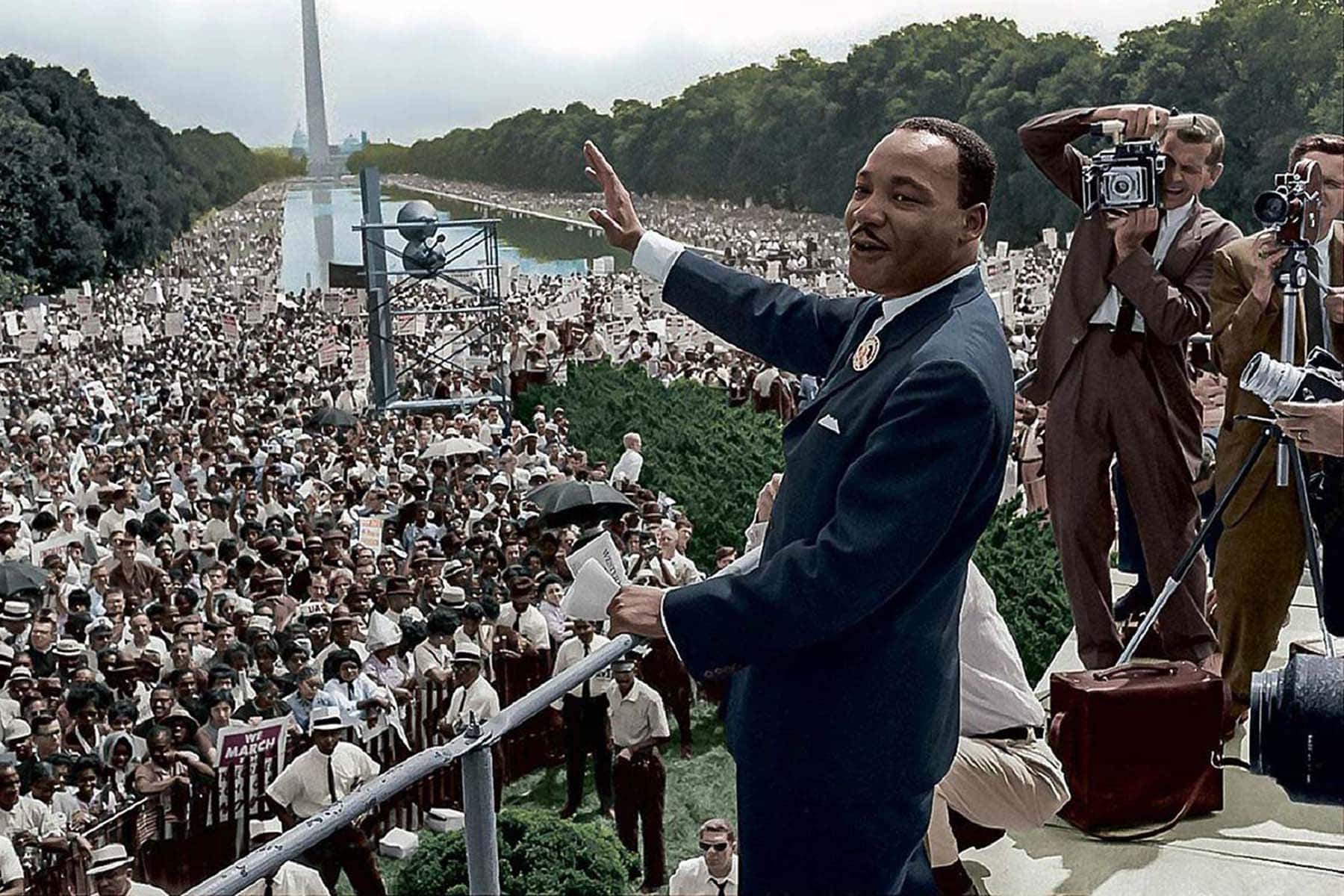

But in that same oft-quoted I Have a Dream speech from 1963, King celebrated the “marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community” and spoke of the “fierce urgency of now”. For his own militancy, King was hounded by the FBI, denounced as a communist and bombarded with death threats. Only 22% of Americans approved of the Freedom Rides fighting segregated transportation. By the mid-1960s, 63% of Americans had an unfavorable opinion of King, according to polls.

Martin Luther King Jr. was a part of a much wider movement, standing alongside socialists such as Ella Baker, Bayard Rustin, and A Philip Randolph in not just attempting to dismantle the Jim Crow system, but replacing it with an egalitarian social democracy.

Despite President Lyndon Johnson’s shepherding of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, ending legal apartheid in the United States, King became even more radical as the decade went on. As he put it in 1967: “We aren’t merely struggling to integrate a lunch counter now. We’re struggling to get some money to be able to buy a hamburger or a steak when we get to the counter.”

King was not willing to drop his internationalist commitments to achieve this change. He had long been a supporter of anti-colonial struggles in developing countries and in an April 1967 address at Riverside church in Harlem, he alienated his liberal allies by challenging the slaughter in Vietnam and the broader system of imperialism that made poor people, black and white alike, “kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools”. Despite rebukes from more than 160 newspaper editorials the next day and his permanent alienation from liberal allies in the Democratic party, he pressed on.

Now calling himself a democratic socialist, through his Poor People’s Campaign, King was set to create the kind of movement that could fight for not just political but economic freedom for all. He wasn’t just a civil rights activist, he was a tribune for a multiracial working class – people who faced poverty, racism and joblessness, but who when banded together could wield tremendous power.

King traveled to Memphis in April 1968, where he was assassinated by the white supremacist James Earl Ray, to support striking sanitation workers. His advisers warned against the trip. There were the threats of his life, and there were other campaigns and commitments too. But King knew he had to be there. He knew what side he was on.

Martin Luther King Jr. was not a prophet of unity. He was a champion of the poor and oppressed. And if we want to truly honor his legacy, we’ll struggle to finish his work.

Bhaskar Sunkara

Library of Congress and Ade Russell

Originally published on The Guardian as Martin Luther King was no prophet of unity. He was a radical

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.