A University of Wisconsin-Madison laboratory is set to resume experiments that could build the foundation of an early warning system for flu pandemics.

The research is based on altering a deadly type of the influenza virus in a way that could make it more dangerous, though, and critics say its approval lacked transparency and creates unnecessary risks.

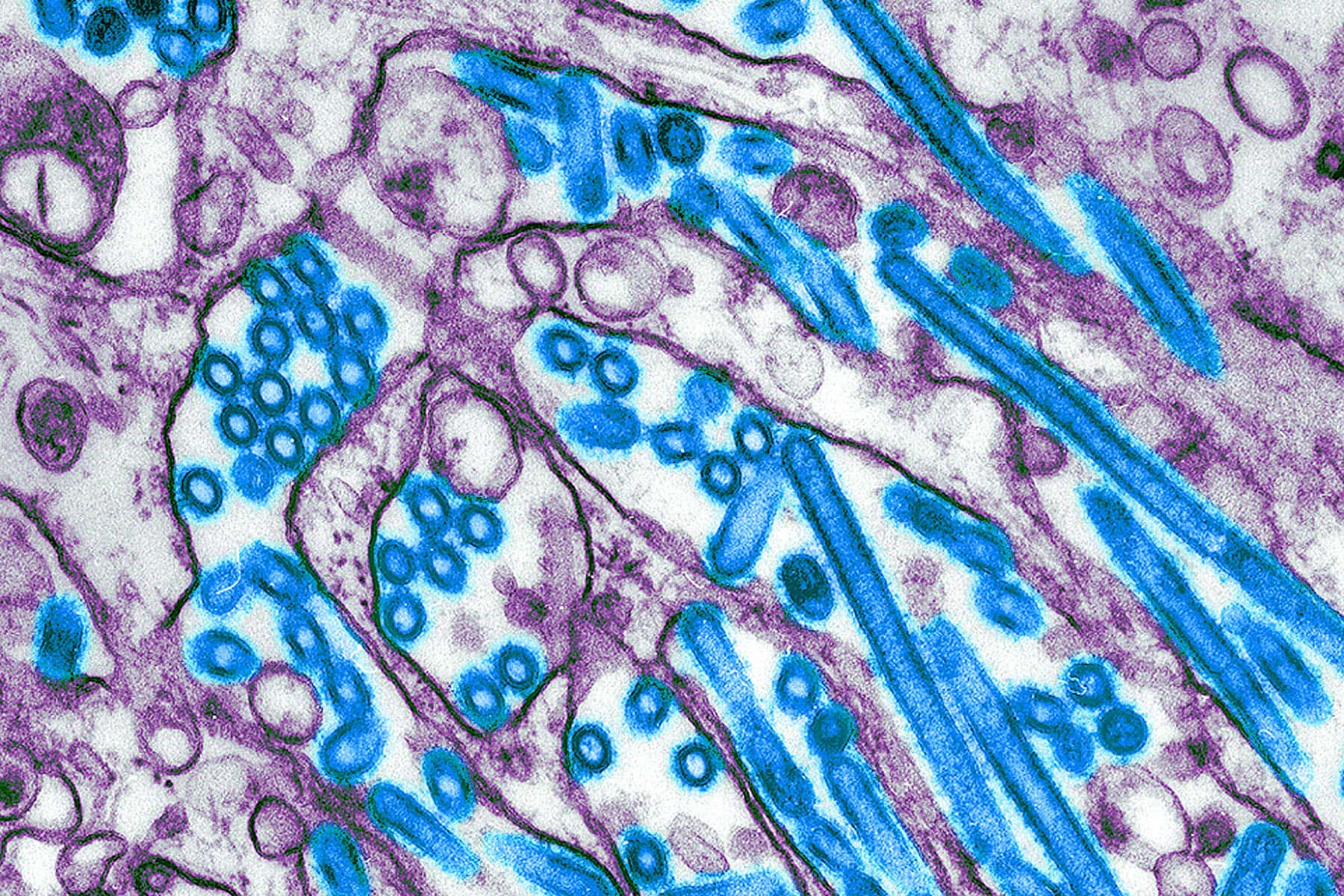

Yoshihiro Kawaoka is a virologist and professor at the UW School of Veterinary Medicine and the University of Tokyo who has figured prominently in Wisconsin’s long-term central role in flu research. Kawaoka’s work has been the focus of fierce debate among epidemiologists ever since he announced in 2011 that his lab had successfully altered the H5N1 subtype of the influenza A virus to be transmittable through the air among ferrets. These small mammals are a common laboratory stand-in for studying human flu transmission.

The H5N1 flu primarily affects birds. On occasion, though, the virus can jump to humans, and can kill more than half of those infected. While deadly, wild H5N1 is confirmed to have infected fewer than 1,000 people around the world. Those who have come down with this virus are thought to have almost always been infected directly from birds with which they were in direct contact. That is why Kawaoka’s 2011 announcement, made around the same time that a research team in the Netherlands made public similar findings, caused a contentious debate in the scientific community.

That debate has lingered since 2011 and intensified in early 2019 after the federal government approved funding for Kawaoka to continue his research.

Marc Lipsitch is a professor of epidemiology and director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He is a longtime critic of research that modifies flu viruses to be more dangerous in humans.

“What worries me and my colleagues is the effort to modify viruses that are novel to humans and therefore to which there’s no immunity in the population, and where a laboratory accident wouldn’t just threaten the person who got infected … but potentially could be the spark that leads to a whole pandemic of infectious disease,” Lipsitch said.

“The issue is that when you take a strain of flu where there’s no immunity in the population because it’s only been circulating in birds, and you modify [it] to transmit, that is creating a potential pandemic pathogen,” Lipsitch said. “The question is whether that’s a good idea or not.”

Lipsitch firmly believes it is not a good idea, and he’s not the only infectious disease researcher who holds this opinion. In 2014, Lipsitch organized the Cambridge Working Group, made up of hundreds of scientists, to call for a reassessment of biosafety measures for viruses altered by researchers. The group formed in response to a series of lab accidents involving potentially dangerous pathogens.

“An accidental infection with any pathogen is concerning. But accident risks with newly created ‘potential pandemic pathogens’ raise grave new concerns,” the group declared in a July 2014 statement calling for a reassessment of experiments like Kawaoka’s. “Laboratory creation of highly transmissible, novel strains of dangerous viruses, especially but not limited to influenza, poses substantially increased risks.”

Assessing risks during a research moratorium

In October 2014, partly in response to the Cambridge Working Group’s concerns, the National Institutes of Health announced a funding moratorium on some types of what’s called “gain-of-function” research, including the H5N1 experiments at the UW, to assess the potential risks and benefits of this work, and review of biosafety standards.

Gain-of-function research aims to identify mutations that give rise to a new genetic function in viruses and microbes. Yoshihiro Kawaoka’s 2011 findings — published in the journal Nature in May 2012 — identified four genetic mutations in the H5N1 virus that made it transmissible among ferrets.

Rebecca Moritz chairs UW-Madison’s biosecurity task force and leads the university’s handling of “select agents,” a class of potentially dangerous subjects of research that includes the H5N1 viruses Kawaoka studies. Moritz has worked closely with Kawaoka to develop safety protocols for his lab, which is located in University Research Park on the west side of Madison.

Moritz spoke on behalf of Kawaoka’s lab and its work. She said that Kawaoka’s research could lead to more effective treatment and prevention options and help build an “early warning detection system” for pandemics by mapping mutations that might make wild H5N1 contagious among humans.

“We don’t understand the mechanisms involved in [influenza] transmission very well,” Moritz said.

She explained that understanding those mechanisms could result in new drugs and approaches to deter the transmission of influenza viruses by identifying certain genetic characteristics that health officials can watch for while monitoring wild strains.

“The goal of this research is not to intentionally create influenza viruses that can transmit,” Moritz added. “Nature is already doing that for us.” She pointed out that the 2011 experiments created an H5N1 virus with less severe symptoms than the wild type, and none of the ferrets died from the infection.

While the goal of Kawaoka and his collaborators is to prevent future flu deaths, their critics point to the risk — however minuscule — of this work of setting off the very health crisis it aims to prevent by way of a lab accident. That prospect is at the heart of objections to the research and why the Cambridge Working Group called for a wholesale reassessment of work like it.

During the federal funding moratorium, NIH sponsored multiple public meetings where the risks and benefits of gain-of-function research on “enhanced potential pandemic viruses” were debated and evaluated. The deliberations included two symposiums of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, held in 2015 and 2016, as well as a 1,000-page risk-benefit analysis and an ethical analysis. Following this process, NIH decided that the benefits outweighed the risks and lifted the funding moratorium in December 2017.

However, the end of the moratorium did not mean that Kawaoka’s research was automatically approved to resume. It took more than a year for NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to reinstate the funding for the UW-based H5N1 research, as Science reported in February 2019. In fact, funding for any “enhanced potential pandemic virus” research must be approved on a case-by-case basis going forward.

“We are glad the United States government weighed the risks and benefits … and developed new oversight mechanisms,” Kawaoka told Science. “We know that it does carry risks. We also believe it is important work to protect human health.”

Transparency is another subject of debate

The way in which NIH disclosed a new round of research at Yoshihiro Kawaoka’s lab at UW-Madison — by way of an update on its public reporter database — did not sit well with critics of the research.

Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch and Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security director Tom Inglesby wrote a Feb. 27 op-ed in the Washington Post with the headline “The U.S. government is funding dangerous experiments it doesn’t want you to know about.”

Lipsitch went further by saying that the federal approval of Kawaoka’s research was “less transparent than the average grant review,” noting that the identities of the reviewers were never revealed. Identifying grant reviewers is standard procedure, Lispitch asserted, and helps guard against conflicts of interest.

“We just don’t know anything about even the identities of the people doing the reviews, although there’s U.S. government policy statements listing the many kinds of expertise that are required to do that work,” Lipsitch said. “We don’t know whether the U.S. government is following its own policy or whether it’s doing something less than that,” he added.

Elleen Kane, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Service’s Assistant Secretary of Preparedness Response, which led the department’s review of the research proposals, declined to identify the reviewers, but shared its framework for guiding funding decisions related to research like Kawaoka’s.

“Reviewers are all federal employees which enables us to avoid conflicts of interest,” Kane commented.

Lipsitch said that, in his opinion, the experiments are less like typical grant-funded research and more akin to a large public works project, and should therefore require an extraordinarily transparent review of the risks and benefits.

He said that a publicized event “where the government said proudly ‘We have decided to fund research that is so groundbreaking and so important to the future of our medical preparedness for pandemics that we think it’s worth risking creating such a pandemic but they’ve done the opposite.”

In response, spokespeople at NIH pointed to its public deliberative process leading up to the funding decision. NIH spokesperson Emma Wojtowicz said that it is providing more materials online. “Moving forward, to increase transparency even more, [the Department of Health and Human Services] is posting projects that fall within the scope of review and have been awarded funding on their website.”

One new condition of federal funding means that the Kawaoka lab has to adhere to new communication standards developed through the NIH’s deliberative process. These include immediately informing officials at NIH if Kawaoka identifies mutations allowing bird influenza strains to be contagious in mammals.

Rebecca Moritz at UW-Madison emphasized the long and public deliberative process leading up to the approval of Kawaoka restarting the research process.

“It involved multiple public hearings, opportunities for public input and input from experts outside the virology field, including Dr. Lipsitch, over the course of four years,” Moritz said. “What has emerged is what the consensus of experts has agreed is best practice.”

Those best practices include maintaining environmental safety procedures used before the moratorium, Moritz said. Kawaoka’s lab is rated as Biosafety Level 3 Agriculture, or BSL-3Ag, which Moritz described as one half-step below the CDC’s highest possible biosafety rating.

“Our biosafety and biosecurity practices are like an onion — layers and layers build on each other to mitigate risks,” Moritz said. “The [lab] is a stand-alone facility expressly built for work with influenza viruses,” she added. “It has built-in redundancies; is constantly monitored by lab personnel, law enforcement and other first-responders; and has more than 500 alarm points.”

Additionally, lab workers are strictly vetted, including undergoing an FBI background check, and must adhere to stringent security protocols. If a fire were to break out in the lab, Moritz said local fire departments have been instructed to let it burn. And if lab workers were to have a medical emergency while inside the facility, they would have to be decontaminated by qualified lab staff before receiving treatment.

Lipsitch pointed out that even some of the most secure labs in the world have dealt with safety breaches, usually due to human error.

“What these experiments do is ramp up the consequences of an accident to a whole new level,” Lipsitch said. “When you take an error-prone process and ramp up the consequences of an error to global pandemic levels, that’s not me being dramatic, that’s just describing what the consequences are of something we don’t need to be doing.”

Originally published on WisContext.org, which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.