Despite recent significant upgrades, questions remain about the effectiveness of Wisconsin’s post-election audits and the security of some voting machines.

Long-time Wisconsin resident and election reformer Jim Mueller said when he was a municipal clerk two decades ago, elections were not a stressful part of small town administration. And, “in my mother’s age, anybody that learned how to count by grade five could be a poll worker,” he said.

His mother worked the polls in the town of Elcho, Wisconsin. In 1999, when Mueller himself became clerk of the town of Middleton near Madison, he expected elections to be straightforward. He just had to learn how to put out the notices, “test the machines, get the ballots printed, set up the polling booth and, you know, maintain your voter registrations and stuff like that.”

Mueller said the process could be arduous, tallying votes into the early morning hours, but it was hardly high drama. In addition to the influence campaigns now attempting to undermine our faith in the electoral process, election infrastructure is being targeted by hackers, including the systems used to register voters and count ballots.

In fact, Mueller became so alarmed by the threats to election security that he helped inspire the creation of Wisconsin Election Integrity, a grassroots watchdog group that routinely challenges the Wisconsin Elections Commission and municipal clerks to plug security gaps and improve systems to detect tampering.

Mueller said voters should understand how their votes are counted — but secrecy around voting machine technology and software limits accountability surrounding a fundamental democratic process. He calls that a “dangerous situation.”

“That should set off the red lights and strobes, alarm bells sounding, you know? People, wake up!”

The Elections Commission, a bipartisan committee tasked with administering the state’s elections, says the state’s election infrastructure is secure. It cites the Election Security Planning Report as evidence of officials’ ability to overcome a range of potential crises.

At the beginning of September, the commission published a detailed report describing how the state has prepared for the November 3 election, including a “candlelight” contingency plan on how to continue without some of the technical services it normally relies on.

Building on these and other sources, Wisconsin Watch sought out local and national election experts to answer the question: How secure is election infrastructure in one of the nation’s top swing states? The answers were mixed.

Wisconsin Watch found that:

- Experts believe Wisconsin’s voter registration system, WisVote, appears to be secure from tampering.

- Most counties are using or plan to use newly available federal funds to help them detect hacking and malware.

- Machines used to tabulate ballots from about 1 million voters in Wisconsin contain modems that, unless properly managed, could make them vulnerable to attack.

- Existing post-election audits may not be able to catch altered or incorrect vote totals.

Although Wisconsin’s election technology is generally seen as secure, the threats against it remain significant. William Evanina, director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, warned in recent months that bad actors may try to compromise election technology as part of a broader effort to undermine faith in the results.

“This threat might take many forms,” Evanina wrote, “such as spreading disinformation, conducting hack-and-leak operations, or possibly manipulating data in a targeted fashion to influence the elections, and involves a wider range of foreign state and non-state actors than we have seen in the past, to include ideologically motivated entities and foreign cyber criminals.”

Voter rolls appear secure

Thanks to recently improved safety protocols and same-day voter registration, experts say Wisconsin’s statewide voter database is not a major vulnerability. Karen McKim, coordinator of Wisconsin Election Integrity, said Wisconsin does an “excellent” job security when it comes to the state’s voter registration system, also known as WisVote.

WisVote is the product of more than a decade of development, put into motion by the Help America Vote Act of 2002, which required all states to have a single, computerized, statewide voter registration system. Previously, local clerks managed their own voter rolls.

According to the Elections Commission, WisVote is now encrypted both on the state’s servers and between the servers and users, who are primarily election clerks and their employees. Additionally, all of the system’s 3,000 users must use multi-factor authentication.

To ensure that these and other protocols are effective, Elections Commission staff now participate in weekly “knowledge transfers” with state and federal law enforcement and intelligence services. The agency also has requested and passed regular cyber hygiene scans from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. These scans identify all internet-facing networks and scan them for common vulnerabilities that hackers could exploit.

“The good folks from Homeland Security have been all up inside our business, both looking for vulnerabilities and looking for evidence of past intrusions. And we got a good, clean bill of health,” Elections Commission spokesman Reid Magney said.

The agency has received training from Homeland Security on how to perform these assessments and plans to offer that service to local jurisdictions, according to the security report. In addition, WisVote lacks the type of automatic features that could be exploited by hackers to delete registrations — a well-known method of attacking voter databases.

In a classic hack of this kind, explained University of Iowa election security expert Douglas Jones, a hacker would add fraudulent registrations to the system, making it look as though a voter had moved, which would trigger an automatic deletion of the voter’s actual address. Russia was poised to exploit this vulnerability in 2016 with the Illinois voter registration database, although it did not carry out the attack, state and federal officials say.

In an email, Magney wrote that WisVote was protected from this kind of exploit. When WisVote identifies a duplicate record like those that would be created during such a hack, clerks must manually resolve the issue. In addition, Magney said WisVote’s segmented design makes it technically impossible for an intruder to access the system through a poorly-protected municipal clerk’s office outside of Madison, for example, and write or delete existing registrations in Madison.

But even if such attacks could somehow delete voters’ registrations, Wisconsin’s policy of same-day registration would mitigate the damage, Jones said. By allowing voters to re-register at the polls, he said, same-day registration effectively neutralizes the threat.

County offices adding security

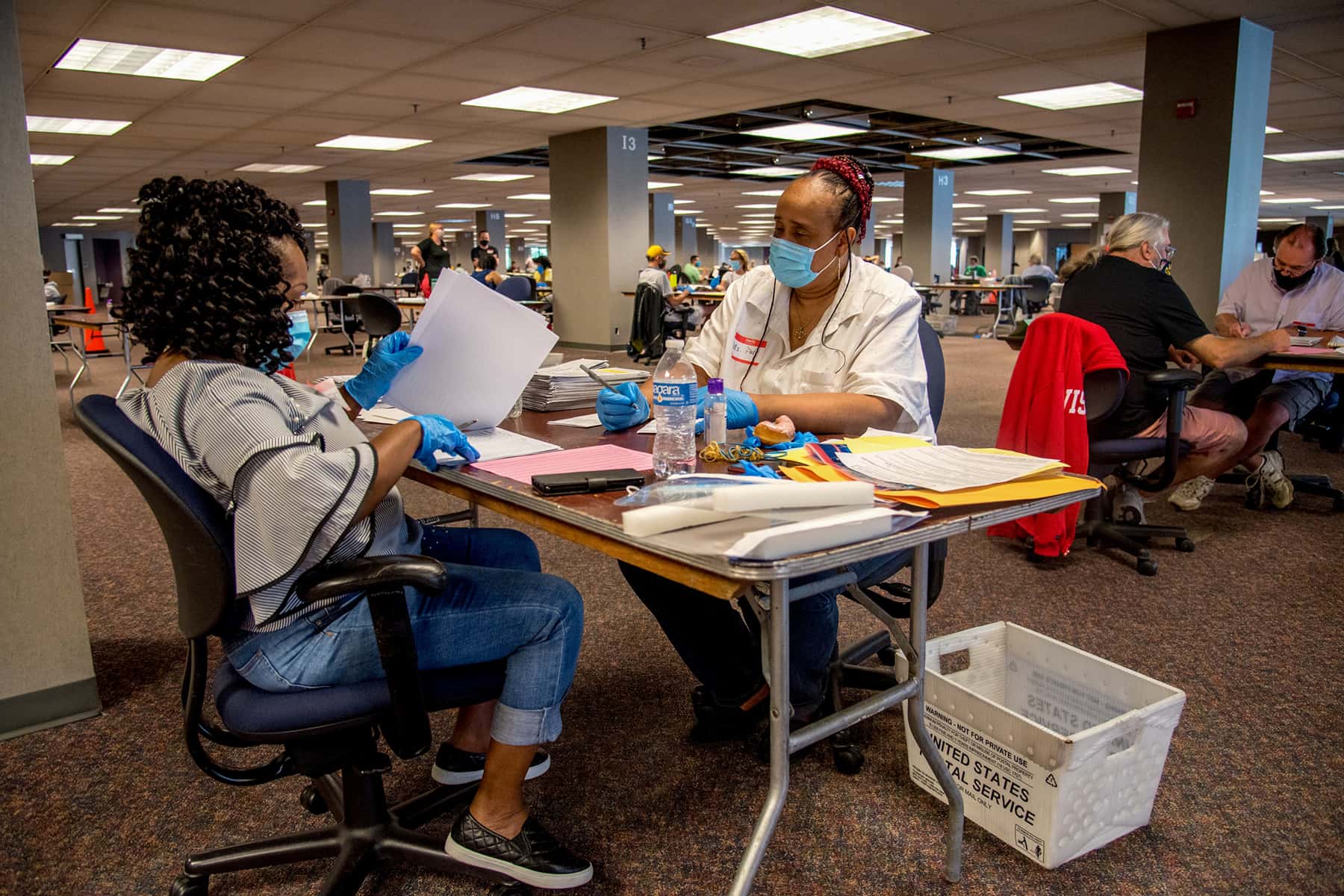

Although Wisconsin’s 1,850 municipal clerks primarily shoulder the burden of election administration, the state’s 72 county clerks and their offices carry out some election-related tasks, making them another potential target. But some of these offices lack basic defenses against a cyberattack.

Dane County Clerk Scott McDonell warned last December that the Elections Commission was planning to spend too little of its latest $7 million federal election security grant to protect county clerks’ offices. These offices program voting equipment, print ballots and tabulate results. The offices also provide municipal clerks in more rural and less resource-rich counties with technical support for voter registration and absentee voting.

According to McDonell, hackers could penetrate county servers and replace unofficial election results with false results, or prevent local governments from sending their results to county collection systems, eroding the public’s confidence in elections.

His warning in December came just one month before Russian hackers paralyzed the computer systems of Oshkosh and Racine. Even though both cities were able to revert to partial backups of their data, it took weeks to recover from the attacks, which in Oshkosh affected finance, collections, utility billing, public safety and internal support services. Officials did not know how the virus had managed to slip past the city government’s security features.

McDonell said Dane County is one of the few counties in Wisconsin that has invested in advanced cyberdefenses — but most counties soon will join in.

At a February 27 meeting of the Elections Commission, McDonell told the commissioners that an outside cybersecurity firm’s audit of Dane County’s computer systems had pointed out enough flaws to inspire him to purchase an Albert sensor — a network monitor that looks for suspicious behavior in a computer system. Ohio used this kind of sensor last year to stop a cyberattack against its election system.

In recent months, Wisconsin’s Elections Commission has taken steps to improve county-level security. On June 10, commissioners approved a new federally funded program for counties to conduct security assessments or to purchase intrusion detection systems. As of July 30, a total of 59 of the state’s 72 counties had applied for funding, and by late August, most had received it, Magney said.

“I think this is a good start but much more needs to be done,” McDonell wrote in an email to Wisconsin Watch. “Overall we are in a much better place than four years ago.”

Voting machines fall short of national standards

The Elections Commission has found no evidence that Wisconsin’s election systems have ever been compromised — and the same is true nationally. “Extensive” attempts by Russia to tamper with the 2016 election failed to breach any machines or change any vote totals, intelligence agencies say.

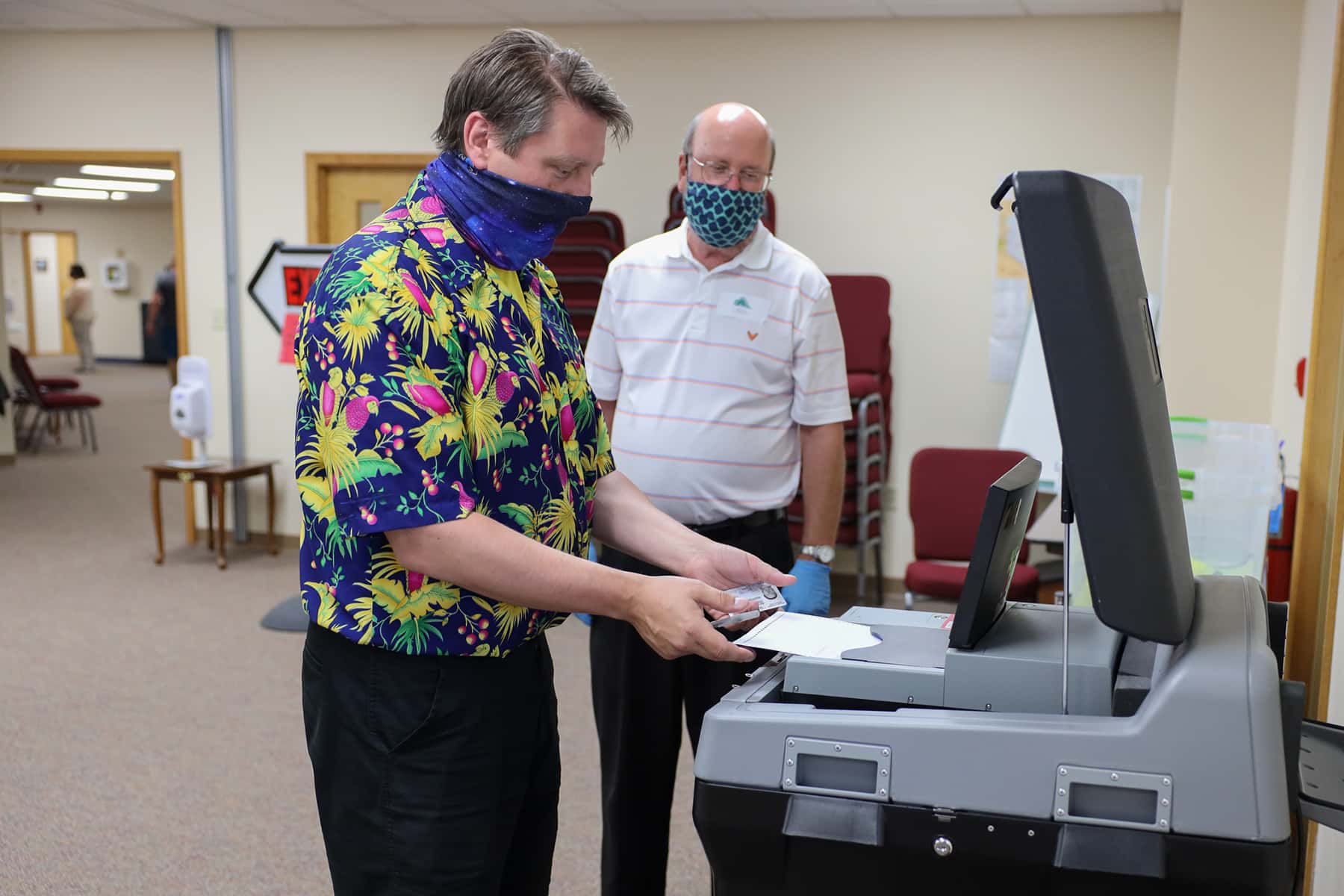

But the voting machines used by roughly 30% of all Wisconsin voters fall short of voluntary federal guidelines designed to protect elections from interference. The voting machine industry has been frequently criticized for a lack of oversight and transparency, despite the central role these machines play in our electoral process.

Lawrence Norden from New York University’s Brennan Center testified before Congress in 2019 that even though election technology has been designated as critical infrastructure, “There are more federal regulations for ballpoint pens and magic markers than there are for voting systems and other parts of our federal election infrastructure.”

And these machines, said McKim, the voting security activist, “are under the complete control of the vendors.” More than 1 million Wisconsin voters use one type of machine at the center of this controversy, a Wisconsin Watch analysis showed: DS200s, which are manufactured by the company, Election Systems & Software, and used in other states.

Across the country, since computer experts first warned about security problems with voting machines, manufacturers and election officials have denied that the machines can be hacked. This is because the systems are not connected to the internet, they say.

Systems found operating online

But in Wisconsin and other states, the systems have been found online. In September 2019, WisPolitics reported that the back-end servers of election systems were connected to the internet for up to a year in seven Wisconsin counties: Outagamie, Dodge, Milwaukee, St. Croix, Columbia, Waukesha and Eau Claire. The systems referred to in the article were taken offline after officials were alerted to the risk.

Magney said all of those systems had “industry-standard firewall protection,” and none of them was breached. In light of the threat posed by internet connectivity, momentum has been building among policy makers to require that voting machines be physically separated from any internet-capable devices.

Last December, the Commerce Department’s National Institute of Standards and Technology recommended that all voting machines be physically separated from the internet. This followed up on the Senate’s Russian interference investigation that recommended that states should stop buying voting machines that have a wireless networking capability.

Additionally, on Feb. 7, after nearly five years of development, a technical working group at the U.S. Election Assistance Commission voted to forward new guidelines that would require all voting machines to be physically separated from the internet to be federally certified. Pressure has mounted against Election Systems & Software to stop falsely advertising that its modemed machines have been certified by the federal elections agency.

In April, the state Elections Commission received a letter from ES&S acknowledging that modemed DS200s had never been federally certified. The company sent that letter to DS200 clients in Wisconsin and elsewhere after the federal elections agency threatened to publicly disclose the lack of certification and possibly suspend ES&S’s manufacturer registration.

In response to questions from Wisconsin Watch while reporting this story, the state Elections Commission changed language on its website to clarify that the voting machines equipped with modems have not received federal certification. Until 2016, Wisconsin state law required that every voting machine in the state comply with federal guidelines. But since then, the Legislature lifted that requirement, and the state Elections Commission can approve any voting machine that meets a list of 18 basic criteria — none of which deals explicitly with the voting machine’s networking capability.

Jones, the election security expert, said Wisconsin voters “should be concerned” by the use of modemed voting machines during elections. But he said such attacks can be thwarted by unplugging modems from the machines until after official results are printed and frequently wiping the computers used to process the official results.

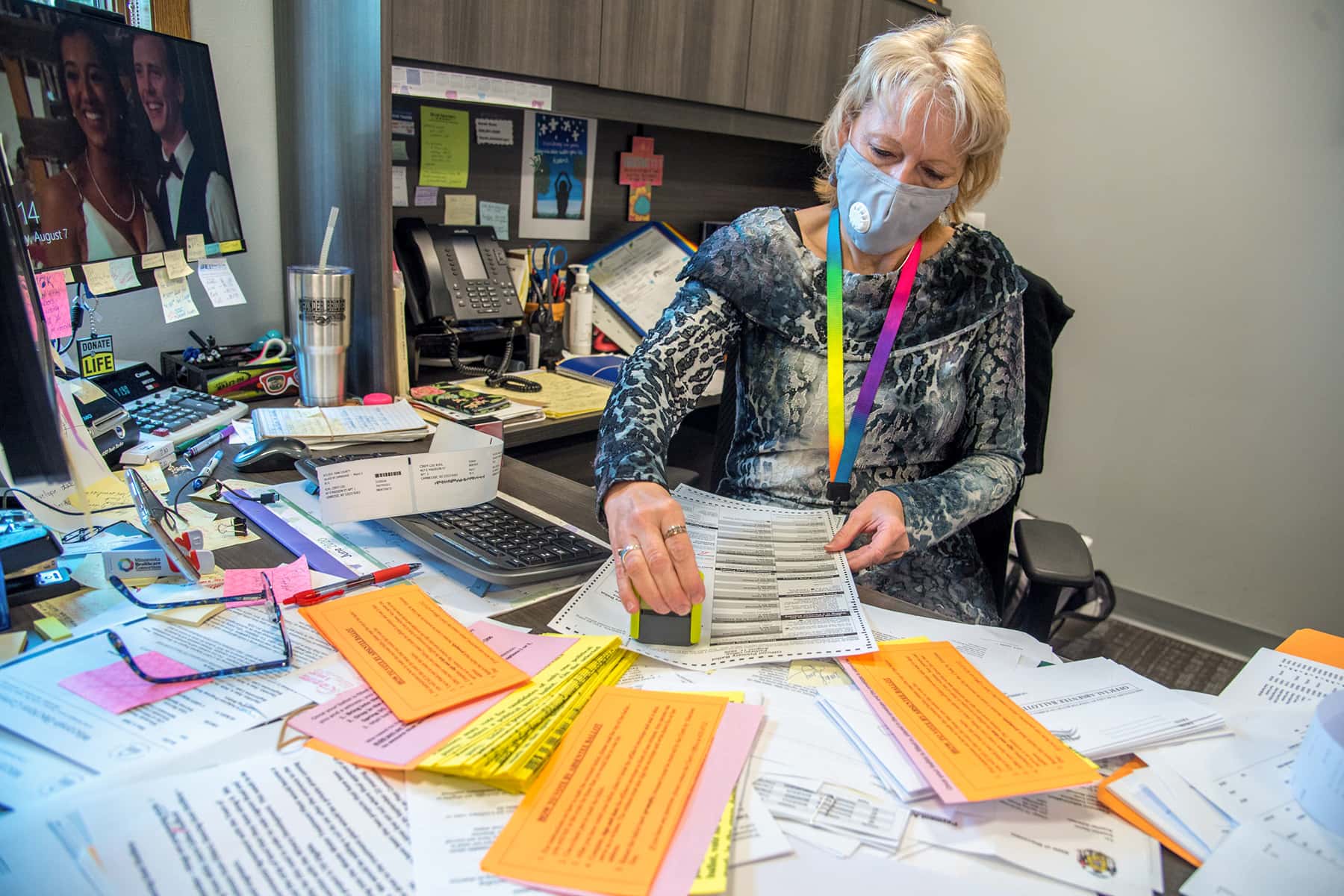

Audits offer weak protections

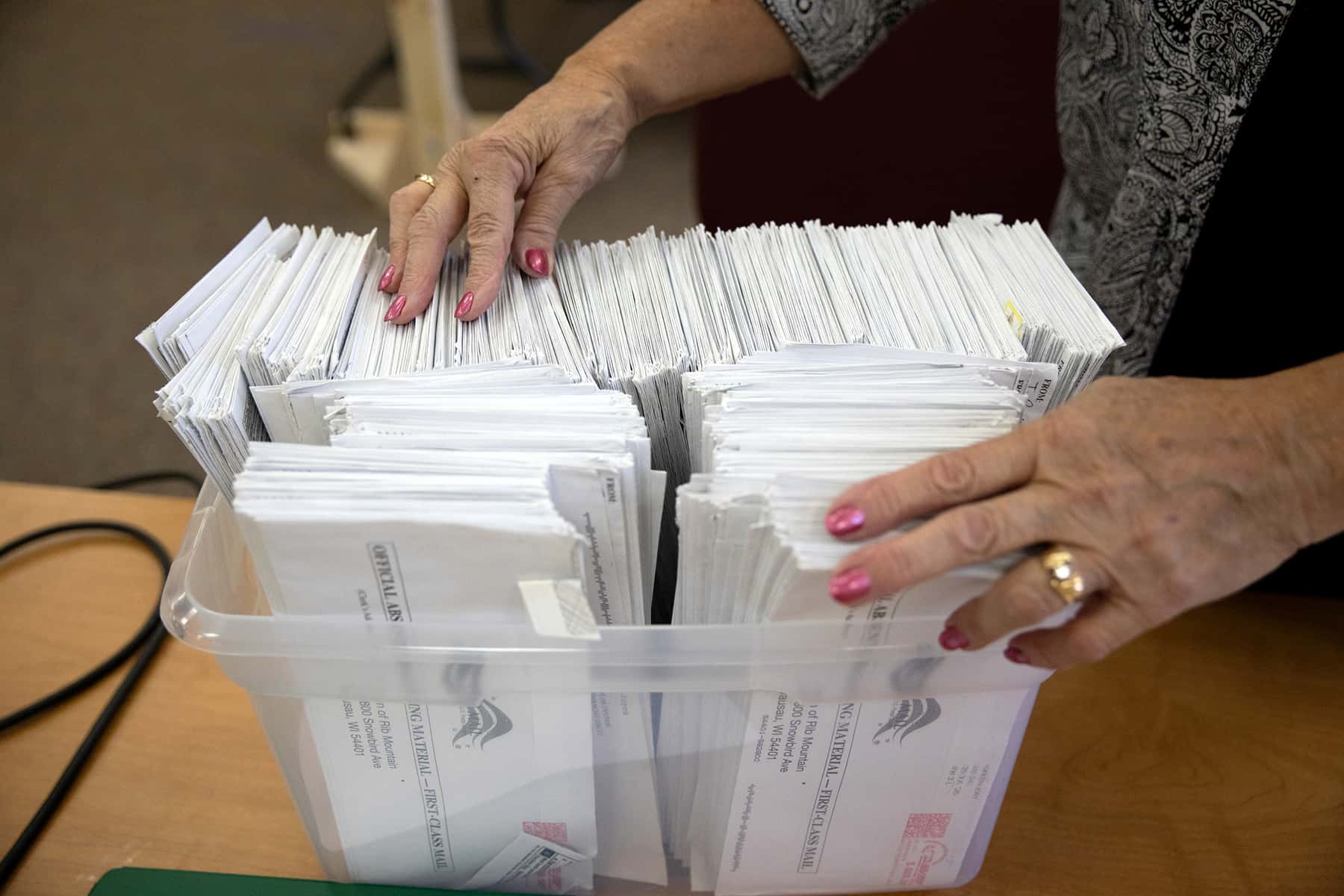

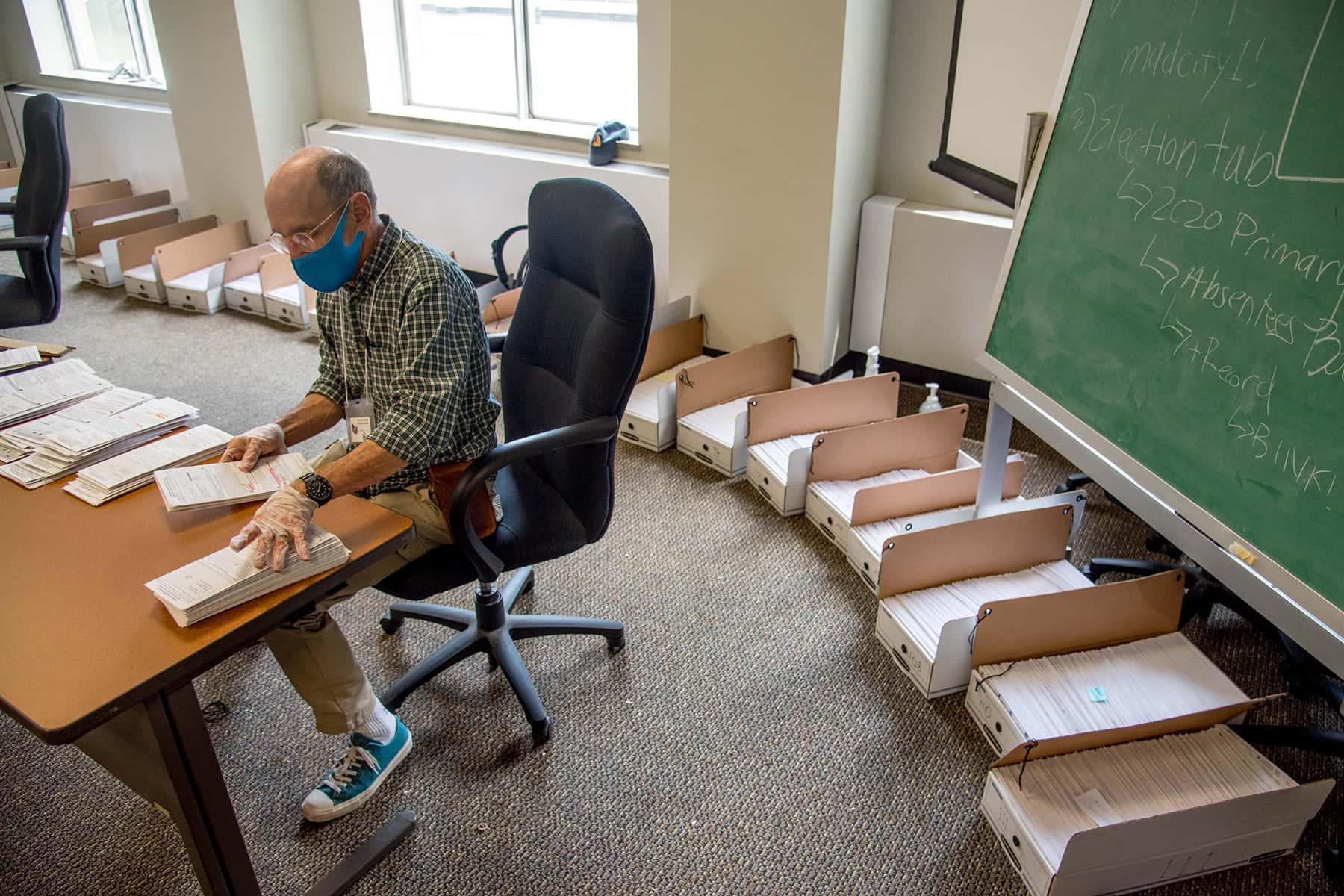

Even though every ballot in Wisconsin is either cast on paper or has a paper backup, the use of paper ballots provides little security without meaningful audit procedures to check how those ballots were counted. State law requires the Elections Commission to audit each voting system in the state to determine the error rate in each system’s counting. In 2018, for example, municipalities hand-counted more than 135,000 ballots from 186 randomly selected jurisdictions and found no issues with the voting systems used in that election.

David Becker, executive director and founder of the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Election Innovation & Research, emphasized that these audit procedures are important to confirm that the machines work properly. That is especially important in close races, like Wisconsin’s 2016 presidential contest in which Donald Trump won the state by less than 1 percentage point.

But when the left-leaning Center for American Progress reviewed Wisconsin’s election security in 2018, it found the state’s audit procedures to be “unsatisfactory.” Even though the Elections Commission expanded the scope of post-election audits after the report was published, the think tank’s main criticism remains: Wisconsin’s audit system checks the accuracy of voting machines — not the election results — which means that even if an audit discovered that the machine-tabulated tallies were incorrect, the election results would remain the same.

However, Magney said if an audit raised questions about a machine’s performance, the Elections Commision would not certify the final results until the issue was resolved.

Even if the audit found significant errors as a result of malfunction or hacking, if the election’s margin of victory was greater than 1%, then by state law — changed after the 2016 statewide recount triggered by Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein — a recount would not be allowed.

Magney said if that were to happen, the Elections Commission would take steps to ensure the correct results are certified — but he acknowledged there is no process currently in place. McKim calls this a major vulnerability.

“Audit practices like those — designed only to reveal but not to correct any hacked results — make Wisconsin catnip for adversaries who want only to disrupt,” she wrote in a recent blog post after making an appeal to the Elections Commission to close the loophole.

McKim fears hackers will meet one of their chief goals — causing chaos, as intelligence officials and experts have recently warned.

“They want the system to freeze up, to be unable to regain its legitimacy, and collapse in recriminations and vicious legal battles,” she said.

Risk-limiting audits pushed

McKim has advocated for the statewide use of risk-limiting audits — a kind of audit that hand counts an increasing number of randomly-selected ballots until the election results have been statistically verified.

In September 2018, the League of Women Voters of Wisconsin also called for the state to adopt risk-limiting audits, following the Center for American Progress’ negative report. Becker does not think the state needs to use risk-limiting audits specifically; any audit that is statistically robust would work. Federal guidelines back this up, saying that many audit designs would be satisfactory, so long as they fulfill the basic requirement of statistically proving that the election results were correct.

The Elections Commission staff has noted that federal officials consider risk-limiting audits as a best practice, and concluded in an internal study that one type of risk-limiting audit could be used in Wisconsin.

But because of the state’s highly decentralized voting system, the agency lacks the legal authority to mandate audits across the state. Commission staff also noted the practical difficulties of coordinating such a statewide audit due to the number of different voting systems used across the state.

Only the Legislature could mandate audits across the state, the agency said. McKim argues that no matter how good the technology is, voters should focus on how well that technology is managed. As she told the Elections Commission in February, she believes Wisconsin has a way to go.

“If Wisconsin election officials still have no orderly procedures in place to detect and correct hacked results,” McKim wrote, “the Wisconsin Elections Commission cannot say they were not warned, and could not have been prepared.”

John Bassett

Coburn Dukehart

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.