By Sarah Azaransky, Associate Professor of Social Ethics, Union Theological Seminary

An annual feast day is held for Episcopal saint Pauli Murray, the first Black woman to be ordained by the denomination: an affirmation of her many contributions not only to the church, but to social justice in the United States.

Saints exemplify “what it means to follow in the footsteps of Jesus and make a difference in the world, and Pauli Murray is one of those people,” Episcopal Bishop Michael Curry said when Murray gained the status of a saint in 2012.

I am a scholar of religion and ethics and have written a biography of Murray and her faith. Throughout her life as an activist, author, lawyer and priest, Murray developed new ways of thinking about justice and identity – ideas important in the U.S. today.

Front line for racial justice

Born in 1910 in Baltimore, Murray jumped into civil rights activism after she graduated from New York’s Hunter College. In the 1940s, she was in the vanguard of Black Christian activists who studied Indian independence leader Mohandas Gandhi’s practice of nonviolent direct action and applied it to the struggle for racial justice in the United States.

More than a decade before Rosa Parks’ arrest for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white rider, Murray was arrested for integrating an interstate bus. She organized sit-ins in segregated restaurants in Washington, D.C., a strategy other activists famously replicated in Greensboro, North Carolina.

In 1956 Murray published “Proud Shoes,” a family memoir that brought attention to how central sexual violence was in the history of U.S. slavery. Murray offered her family – who was Black, white and Indigenous, and whose ancestors were both enslaved and free – as an emblem of the nation, and an example of the history all Americans needed to reckon with.

Feminist and priest

As a lawyer, Murray used her career to advocate for racial justice. But she also grew increasingly involved with advocacy for women’s rights, to which she made landmark legal contributions.

In the 1960s, Murray laid the groundwork by encouraging feminist lawyers to move away from seeking special protections for women and instead argue for equal rights. Supreme Court Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg credited Murray with teaching her how appealing to the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment could be an effective method to fight sex discrimination. After hearing Murray argue that there should be an NAACP – the country’s oldest civil rights organization – just for women, feminist leader Betty Friedan invited Murray to a strategy session where the National Organization for Women was founded.

A lifelong Episcopalian, Murray made a dramatic-seeming move to enroll in a seminary when she was in her mid-60s. Yet to Murray, it made perfect sense. She described preparing for the ministry as one more way to address questions of human rights and social justice.

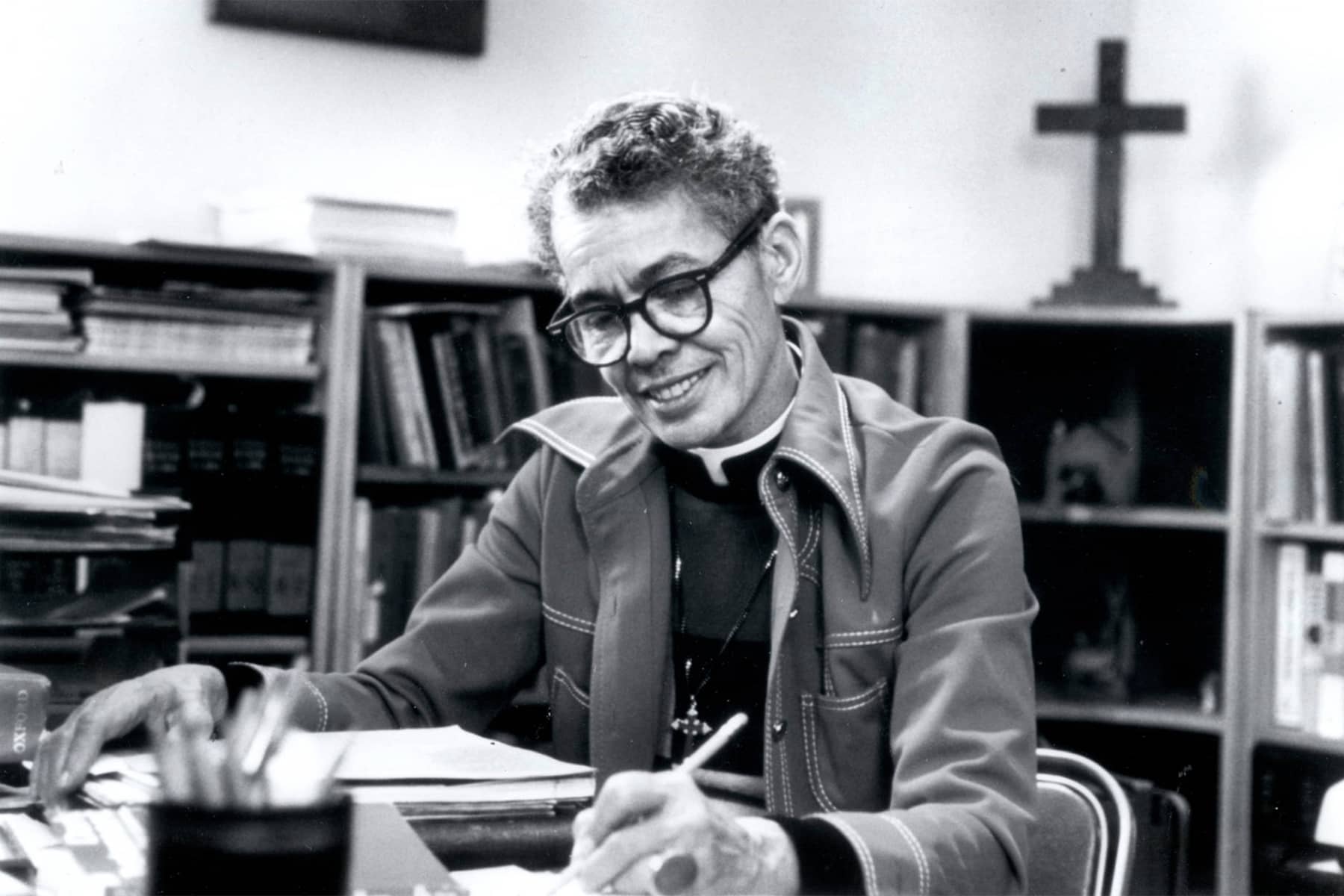

Murray entered seminary before the Episcopal Church began ordaining women and organized with others to push for women’s ordination. In January 1977, she became one of the first women, and the first Black woman, to be ordained.

Murray indeed contained multitudes, including when it came to gender identity. At some points in life Murray identified as a man; at others, as a woman. Murray was in long-term romantic relationships with women, but did not publicly identify as lesbian or queer.

When she prepared her papers to be archived, Murray included writings about her multiple gender and sexual identities so they would be available for future generations. During her life, categories like “nonbinary” or “trans” were not used, but many scholars and admirers today see her as an early icon for transgender people.

Written into law

Another way Murray’s work seems prescient today is her focus on what’s now called “intersectionality”: how multiple aspects of a person’s identity, such as race, gender, income and nationality, intersect to shape their privilege or oppression.

A prime example is Murray’s phrase “Jane Crow” – a spin on “Jim Crow” – which she coined to describe Black women’s experiences of being discriminated against because of racism and sexism. In a world where “male supremacy” and “white supremacy” are prevalent, a Black woman “finds herself at the bottom of the economic and social scale,” Murray wrote in 1947.

Murray’s “Jane Crow” has made important contributions in American history. In 1964, for example, she employed the concept to keep “sex” as a category in Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, making it unlawful to discriminate against someone in employment based on race, color, national origin, sex or religion. Some lawmakers thought “sex” was a distraction in a law that focused on discrimination based on race. As a Black woman, Murray argued that both race and sex needed to be included if the law were to protect people like her.

Murray’s insistence on including sex in Title VII has become essential to LGBTQ rights today. The landmark 2020 Supreme Court ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County prohibits employers from firing people because they are gay or trans. Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, who wrote the majority opinion, wrote, “It is impossible to discriminate against a person for being homosexual or transgender without discriminating against that individual based on sex.”

Murray’s capacious sense of being a human, which she gleaned in part from her own experiences, inspired her many contributions to social justice. In a letter to friends soon after her ordination, Murray wrote, “we bring our total selves to God, our sexuality, our joyousness, our foolishness. … I’m out to make Christianity a joyful thing.”

Carolina Digital Library and Archives/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Originally published on The Conversation as The Episcopal saint whose journey for social justice took many forms, from sit-ins to priesthood

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.