Heather Cox Richardson offers an eloquent history of the negation of the American idea, with clear lessons for the November election.

Heather Cox Richardson’s How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America is not principally about that war. Instead, it is a broad sweep of American history on the theme of the struggle between democracy and oligarchy – between the vision that “all men are created equal” and the frequency with which power has accumulated in the hands of a few, who have then sought to thwart equality.

What she terms the “paradox” of the founding – that “the principle of equality depended on inequality”, that democracy relied on the subjugation of others so that those who were considered “equal”, principally white men, could rule, led to this continuing struggle. She draws a line, more or less straight, between “the oligarchic principles of the Confederacy” based on the cotton economy and racial inequality, western oligarchs in agribusiness and mining, and “movement conservatives in the Republican party.”

More specifically, she writes that the west was “based on hierarchies”. California was a free state but with racial inequality in its constitution. Racism was rife in the west, from lynchings of Mexicans and “Juan Crow” to killings of Native Americans and migrants who built the transcontinental railroad but were the target of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

There, aided by migration of white southerners, “Confederate ideology took on a new life, and from there over the course of the next 150 years, it came to dominate America.” This ranged from western Republicans working with southern Democrats on issues like agriculture, in opposition to eastern interests, to shared feelings on race.

Once Reconstruction ended, and with it black voting in the south, Republicans looked west. Anti-lynching and voting rights legislation lost because of the votes of westerners, and new states aligned for decades more “with the hierarchical structure of the south than with the democratic principles of the civil war Republicans,” thanks to their reliance on extractive industries and agribusiness.

For Richardson, Barry Goldwater’s opposition to the Civil Rights Act in 1964 was thus not an electoral strategy but a culmination of a century of history between the south and west, designed to preserve oligarchic government in “a world defined by hierarchies”. Richardson sees Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and the reaction against it as “almost an exact replay of Reconstruction.” What she terms the “movement conservative” reaction promoted ideals of individualism – but cemented the power of oligarchies once again.

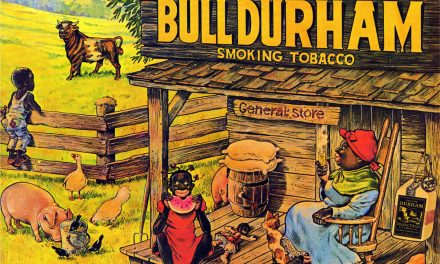

But isn’t America the home of individualism? Richardson agrees, to a point. The images of the yeoman farmer before the civil war and the cowboy afterwards were defining tropes but ultimately only that, as oligarchies sought to maintain power. Indeed, she believes, during Reconstruction, “to oppose Republican policies, Democrats mythologized the cowboy, self-reliant and tough, making his way in the world on his own,” notably ignoring the brutal work required and the fact that about a third of cowboys were people of color.

These tropes mattered: “Just as the image of the rising yeoman farmer had helped pave the way for the rise of wealthy southern planters, so the image of the independent rising westerner helped pave the way for the rise of industrialists.” And for Jim and Juan Crow and discrimination against other races and women, which put inequality firmly in American law once again.

Yet ironically, as in the movies, the archetype came to the rescue: “Inequality did not spell the triumph of oligarchy, though, for the simple reason that the emergence of the western individualist as a national archetype re-engaged the paradox at the core of America’s foundation.” In the Depression, “when for many the walls seemed to be closing in, John Wayne’s cowboy turned the American paradox into the American dream.” Wayne’s Ringo Kid in Stagecoach marked the emergence of the western antihero as hero.

Indeed, the flame was never fully extinguished despite the burdens of inequality on so many. In Reconstruction, the Radical Republicans fought for equality for black people. The “liberal consensus” during and after the second world war promoted democracy and tolerance. Superman fought racial discrimination.

In all it is a fascinating thesis, and Richardson marshals strong support for it in noting everything from personal connections to voting patterns in Congress over decades. She errs slightly at times. John Kennedy, not Ronald Reagan, first said “a rising tide lifts all boats” – it apparently derives from a marketing slogan for New England; she is too harsh on Theodore Roosevelt’s reforms; and William Jennings Bryan – a western populist Democrat who railed against oligarchy even as he did not support racial equality – belongs in the story.

Richardson has achieved prominence for her Letters from an American series, which daily chronicles the latest from the Trump administration. As with many American histories these days, Trump and Trumpism form a backdrop to her work. She subtly draws connections between echoes of the past and actions of the Trump administration which appear as their natural, if absurd, conclusion.

As Richardson writes, after the Kansas-Nebraska Act extended the possibility of slavery in those territories, “moderate Democrats were gone, and slave owners had taken control of the national party”. She needn’t finish the analogy, other than to say that “[t]he world of 2018 looked a lot like that of 1860.”

The broader question is vital: does American democracy somehow require the subjugation and subordination of others? Richardson eloquently and passionately accounts why that principle is so dangerous and damaging.

Refuting it – precisely by asking America to extend the benefits of the founding to everyone – is the principal task for Americans today. She concludes that “for the second time, we are called to defend the principle of democracy” – something that can be done only by expanding its definition in practice to match the ideal. Only in that way can the American paradox be resolved.

Or, as Joe Biden recently said in fewer words: “Democracy is on the ballot.”

Heather Cox Richardson on How the South Won the Civil War

Defending Democracy: Doris Miller’s legacy at Pearl Harbor faces Trump’s authoritarian ambitions

On the sunny Sunday morning of December 7, 1941, Messman Doris Miller had served breakfast aboard the USS West Virginia, stationed in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and was collecting laundry when the first of nine Japanese torpedoes hit the ship. In the deadly confusion,...

Democracy Defended: South Koreans overturn stunning self-coup and reverse Martial Law in 6 hours

For an astonishing six hours today, South Korea underwent an attempted self-coup by its unpopular president, Yoon Suk Yeol, only to see the South Korean people force him to back down as they reasserted the strength of their democracy. In an emergency address at nearly...

Reshaping government: Why Movement Conservatives attacked the liberal consensus to subvert democracy

Cas Mudde, a political scientist who specializes in extremism and democracy, observed recently on Bluesky that “the fight against the far right is secondary to the fight to strengthen liberal democracy.” That is a smart observation. During World War II, when the...

John S. Gаrdеer

Jаsоn Rеdmоd

Portions originally published on The Guardian as How the South Won the Civil War review: the path from Jim Crow to Donald Trump

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.