There had never been a presidential election like this: The Republican Party is split into bickering factions and unable to unite behind its candidate, while the Democratic Party is in disarray following a bitter nomination process. Adding to the turmoil, candidates from two small parties are attracting unprecedented support.

Now one of those upstart candidates is coming to Milwaukee, where an assassin will fire a bullet into his chest.

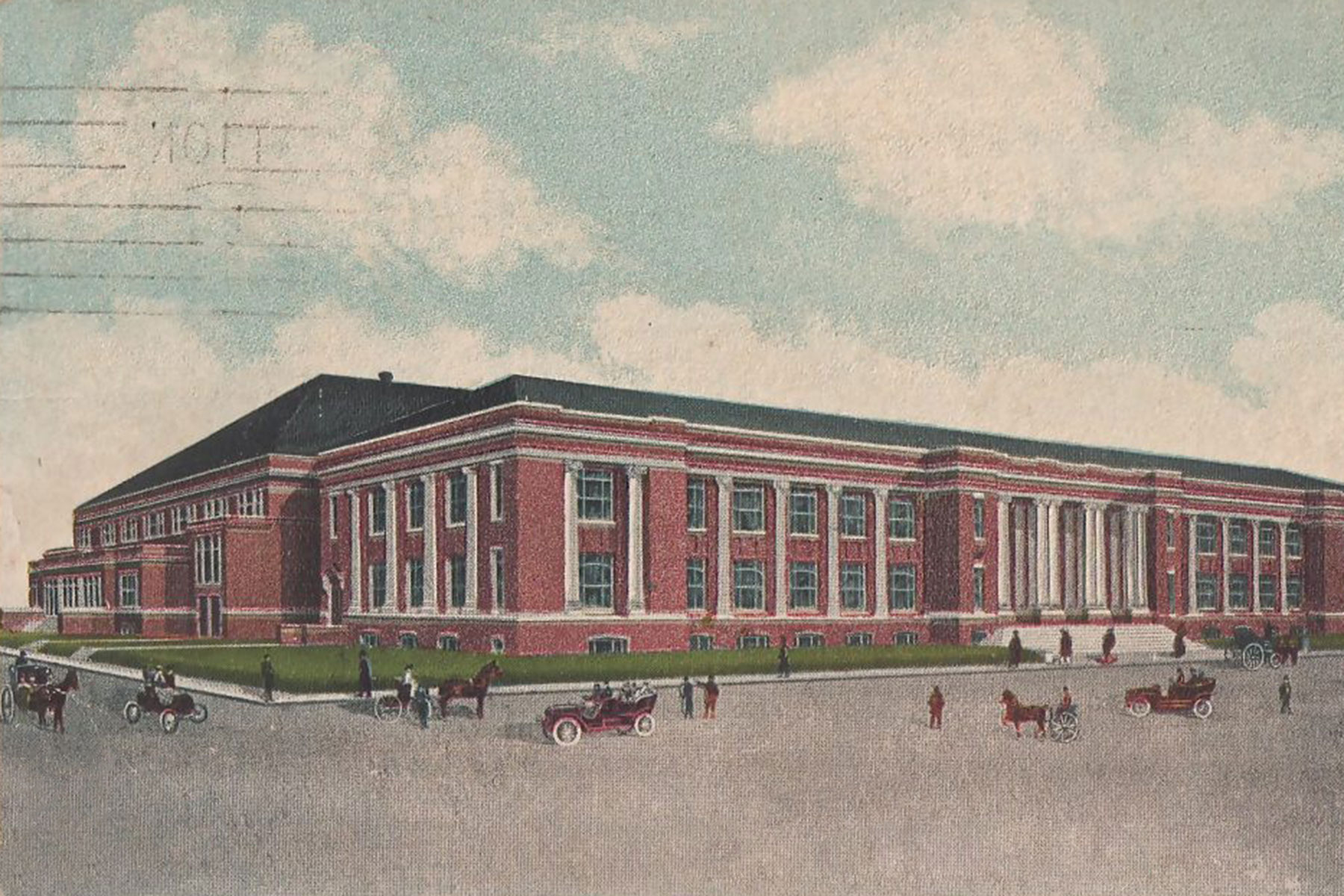

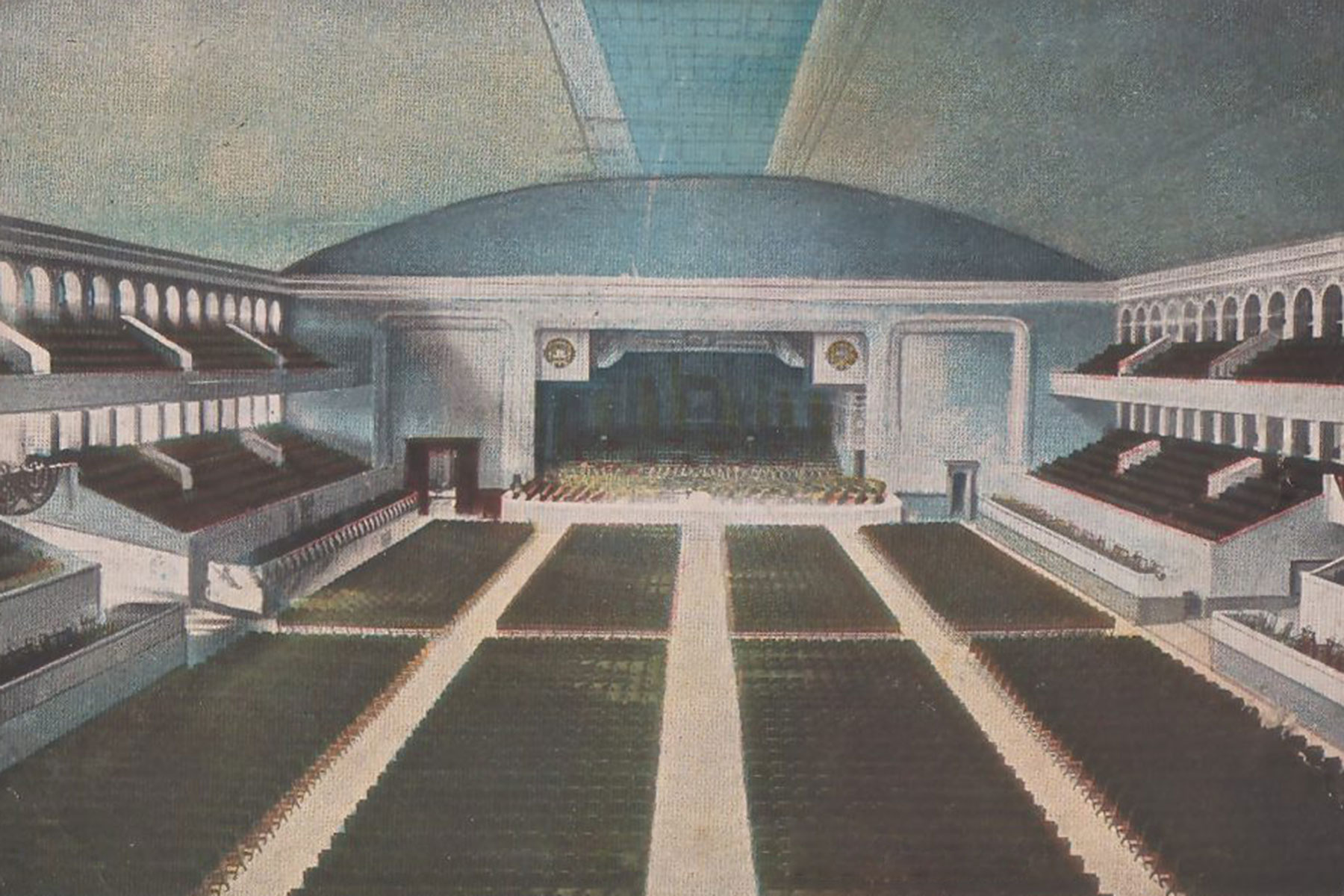

It is Oct. 14, 1912, and Theodore Roosevelt is scheduled to speak at the Milwaukee Auditorium. Covering a city block, the auditorium holds 9,000. An overflow crowd is gathering, eager to hear the popular former president make his case as the candidate of the new “Bull Moose” party. John Flammang Schrank, a New York saloonkeeper, is also in Milwaukee. He had followed Roosevelt from city-to-city for nearly a month. There is a gun in his pocket.

Roosevelt is a fascinating character. Born to a wealthy family, he once worked as a cowboy and became a president. He was a popular author and a respected historian, an avid hunter and an avid conservationist. He fought bravely in the Spanish-American War and won the Nobel Peace Prize for helping end the Russo-Japanese War.

While still governor of New York, Theodore Roosevelt ran as William McKinley’s running mate in the president election of 1900. McKinley won in a landslide. A year later, McKinley was assassinated and Roosevelt, at age 42, became president. He won a full term as president in 1904.

He supported fellow Republican William Howard Taft as his successor in office in 1908, but the two had a falling out after Taft won the presidency. Roosevelt sought the Republican nomination in 1912. When that failed he announced an independent run under the newly formed Progressive Party.

Roosevelt told reporters he was ready for the campaign, saying he felt as strong as a bull moose. The comment lent a name to the new organization: the Bull Moose Party.

The Democrats, in one of the most contentious party conventions in its history, nominated Woodrow Wilson. There were seven contenders for the spot and at one point Wilson had been so far out of the running he prepared a concession speech.

The 1912 election also attracted considerable popular support for the Socialist Party and its candidates Eugene V. Debs and running mate Emil Seidel of Milwaukee.

In midst of this political maelstrom, Theodore Roosevelt arrived in Milwaukee aboard a private railcar. Roosevelt had dinner with party leaders at the Hotel Gilpatrick, 831 N. Third St., just two blocks from the Auditorium. At 8:10 p.m., he emerged from the hotel and climbed into a waiting open-top automobile for the short drive to the auditorium. An enthusiastic crowd was on hand, filling the entire block. In response to their cheers, Roosevelt stood in the car to wave.

At that moment, Schrank drew a .38-caliber revolver, rushed forward, and from four feet away fired a single shot into Roosevelt’s chest.

The bullet passed through the former president’s coat, through a 50-page speech folded double, through a steel eyeglasses case, and through a double fold of heavy suspenders before entering his body, shattering a rib, and lodging in the muscles of Roosevelt’s ribcage.

Had it not spent so much of its force passing though the objects in his pocket, doctors later concluded the bullet would have proven fatal.

His assailant was immediately wrestled to the ground by Roosevelt’s staff, a police officer, and bystanders. More police converged, took charge of Shrank, and hauled him through the now-frenzied crowd into the hotel, out a back exit, and off to the Central Police Station.

Roosevelt waved to reassure onlookers, then insisted he be taken to the auditorium. Milwaukee lawyer Henry P. Cochems, a Bull Moose supporter, was in Roosevelt’s car at the time, and wrote of his experiences in a book entitled, <

“By the time we had arrived at the hall,” Cochems wrote, “the shock had brought a pallor to his face. On alighting he walked firmly to the large waiting room in the back of the Auditorium stage, and there Drs. Sayle, Terrell, and Stratton opened his shirt exposing his right breast. Just below the nipple of his right breast appeared a gaping hole. They insisted that under no consideration should he speak, but the Colonel asked: ‘Has any one a clean handkerchief?’ Some one extending one, he placed it over the wound, buttoned up his clothes and said: ‘Now, gentlemen, let’s go in,’ and advanced to the front of the platform.

“I, having been asked to present him to the audience,” wrote Cochems, “after admonishing the crowd that there was no occasion for undue excitement, said that an attempt to assassinate Col. Roosevelt had just taken place, that the bullet was still in his body, but that, he would attempt to make his speech as promised. As the colonel stepped forward, someone in the audience said audibly, ‘Fake:’ whereupon the Colonel smilingly said: ‘No, it’s no fake,’ and opening his vest the blood-red stain upon his linen was clearly visible.

“A half-stifled expression of horror swept through the audience. About the first remark uttered in the speech, as the Colonel smiled broadly at the audience, was, ‘It takes more than one bullet to kіII a Bull Moose.’ ”

William George Bruce was in the auditorium that night. In his book, History of Milwaukee City and County, published in 1922, he wrote, “The audience was at first expectant and amazed, and then horror-stricken. Roosevelt had been shot by an assassin! His breast was bleeding. Where was the bullet? But, there be stood bravely, defiantly, erectly. Behind him sat men in the attitude of catching him in their arms should he fall.

“He began to speak. His voice was faint, hoarse, and high pitched. It gained in strength and volume as be continued.

Gradually the truth dawned upon them. Roosevelt had been assassinated! Some political fanatic, some crank, some enemy had shot him! The assassination of Garfield and McKinley came into mind. What a humiliation to the Republic! What a humiliation to Milwaukee! Tomorrow it would he heralded to the world that a leading American statesman had been assassinated in one of the most peaceful, law-abiding cities on the continent.”

Roosevelt read his speech, each page of which had been pierced by the bullet now in his chest. He spoke for 80 minutes, denouncing the major political parties and urging Americans to unite under the progressive ideals of his Bull Moose Party.

“I ask in our civic life,” Roosevelt said, “that we pay heed only to the man’s quality of citizenship, to repudiate as the worst enemy that we can have whoever tries to get us to discriminate for or against any man because of his creed or his birthplace. Now, friends, in the same way I want our people to stand by one another without regard to differences or class or occupation.”

Bruce wrote, “Those who saw Roosevelt that night will never erase him and the dramatic incident from their memory.”

Concluding his remarks, Roosevelt was driven to Johnston Emergency hospital. After examining x-rays, doctors concluded it would be safer to leave the bullet where it was and that the President was in no immediate danger. At midnight an ambulance carried him to his waiting train for a return to Chicago for further recuperation.

Before he left, the former president fell into conversation with nurse Elvina Kueko, who told Roosevelt she was sorry the shooting had happened in her city. “The Colonel consoled her by saying it might have happened anywhere,” Bruce wrote.

Of his Milwaukee speech Roosevelt later said, “I did not think the wound was dangerous. I was confident that it was not in a place where much harm could follow, and therefore I wished to make the speech. Anyway, even if it went against me, if I had to die, I thought I’d rather die with my boots on.”

Roosevelt was not able to resume his campaign in the month remaining before the election, which was won by Woodrow Wilson.

When John Shrank, 5 feet 4 inches tall, was searched at the central police station, a number of documents were found on his person expressing his determination to kіII the former president. The nature of the writings left little doubt Shrank was mentally ill.

Appearing before a Milwaukee judge, Shrank plead guilty to the shooting. He added, “I did not intend to kіII the citizen Roosevelt, I intended to kіII Theodore Roosevelt, the third termer. I did not want to kіII the candidate of the progressive party. I shot Roosevelt as a warning to other third termers.”

The judge ordered Shrank undergo a psychological examination. The report of the examining doctors determined he belonged to “a class of paranoiacs having insane delusions accompanied by a delusion of grandeur.”

The doctors found him to be, “self-confident, profoundly self-satisfied; dignified and fearless, courteous and kindly. He showed a sense of humor, was cheerful and calm under circumstances that severely test those qualities. … He gave the impression that he felt himself to be an instrument in the hands of God, and that he is a hero like Joan d’Arc and other saviors of nations. At no time did he express or exhibit remorse for his act.”

Theodore Roosevelt died peacefully in his sleep in his home at Oyster Bay, N.Y., on Jan. 6, 1919. He is one of four presidents depicted on Mount Rushmore. According to the National Park Service, he was selected for the honor for his leadership during a time of rapid economic growth, for the construction of the Panama Canal, and for his work to end large corporate monopolies and ensure the rights of the common working man.

John Shrank was sent to the Northern Hospital for the Insane at Oshkosh, Wis. He died on Sept. 15, 1943. He never had a visitor in his 30 years at the institution.

Carl Swanson Collection (Postcards) and the National Archives (Historical Photos)