Research into Voter ID laws nationwide shows that their effect caused a lower turnout in Wisconsin and other states, affecting students, people of color, and elderly, making it much harder for disadvantaged demographic groups to vote.

With all of her necessary documentation, University of Wisconsin-Madison student Brooke Evans arrived at her polling place on November 8, 2016, for the presidential election. For her, voting that day meant not only casting a ballot for the first female presidential candidate with a real shot of winning, but having a voice in a society in which homeless people such as herself were marginalized.

“There’s something about voting that makes you very real,” Evans said. “The United States had to acknowledge that I’m a real human being and I’m here.”

But when poll workers examined her mailing address under the guidelines of the Wisconsin voter ID law enacted in 2015, the University of Wisconsin-Madison philosophy major initially was barred from voting due to confusion over her address.

The law requires Wisconsin residents to present certain forms of photo identification to vote but does not require that the ID have the voter’s current address. Such voters must provide proof of their current address — and that is where Evans ran into trouble.

Not only did Evans, as a college student, face increased obstacles under the voter ID law, her homelessness was another barrier — one that almost prevented her from exercising a fundamental right of citizenship.

“I was just really surprised at the hassle I was given,” Evans said.

Over the past 15 years, voting has become increasingly difficult for people such as Evans. A recent PRRI/The Atlantic 2018 Voter Engagement Survey found that 5 percent of Wisconsinites surveyed said they or someone in their household was told they lacked the proper documentation to vote. (Full disclosure: The Joyce Foundation is a funder of the survey and also is a funder of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism’s coverage of democracy issues.)

A 2014 U.S. Government Accountability Office report concluded that voter ID laws may reduce voter turnout. The report examined 10 studies, as well as turnout in Kansas and Tennessee compared to other states without voter ID laws. The GAO estimated turnout was cut by up to 2.2 percentage points in Kansas and 3.2 percentage points in Tennessee in the 2008 and 2012 elections — with larger decreases seen among specific groups, including those ages 18 to 23, newly registered voters and African-Americans.

Such a margin can be decisive. In 2016, Republican Donald Trump won Wisconsin by less than 1 percentage point, or 47.22 percent of the vote, edging out Democrat Hillary Clinton, who got 46.45 percent.

Republican Attorney General Brad Schimel has even credited the photo ID requirement with helping Trump win Wisconsin — the first GOP presidential candidate to take the state since 1984. Wisconsin was one of three states that handed the presidency to Trump.

Photo ID laws spread nationwide

Although requiring voter identification in some form has a history stemming back to the 1950s, laws requiring all voters without exception to have specific forms of identification gained traction in 2005 after Indiana and Georgia adopted such requirements.

Currently 34 states have voter ID laws in place, with Georgia, Indiana, Kansas and Wisconsin being some of the strictest, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Except for people with religious objections, all voters in Wisconsin are required to present a photo identification at the polls. These include state-issued driver’s licenses and identification cards, U.S. passports and certain IDs issued by Wisconsin accredited universities or colleges.

Wisconsin’s photo ID requirement passed in 2011 and was prompted by Republican concerns about ostensible voter fraud. But that justification has been discredited by several subsequent studies and rejected by a federal judge who in 2016 labeled concerns over voter fraud “mostly phantom.”

In that decision, U.S. District Judge James Peterson struck down parts of Wisconsin’s voter ID law, while still keeping the requirement in place, calling it a “cure worse than the disease.”

So after years of legal wrangling, Wisconsin’s photo ID requirement was put in place for the first general statewide election in 2016.

In Wisconsin, voter ID enjoys strong support from the public. Marquette Law School polls taken between 2012 and 2014 showed between 60 and 66 percent of Wisconsin residents surveyed favored requiring a government-issued photo identification card to vote. It should be noted that among those answering the poll in 2014, 99 percent said they had a valid photo ID to vote.

There are still lingering challenges to the law. The federal appeals court in Chicago has not issued a ruling in two cases despite hearing arguments in February 2017. One lawsuit, brought by One Wisconsin Institute, seeks to strike down the law. Another, brought by the American Civil Liberties Union seeks, among other things, to ease requirements for Wisconsin residents who do not have easy access to the documents needed to obtain a photo ID.

State officials counter that people who lack birth certificates or face other barriers to proving their identity can get temporary credentials while the state researches their identity. But lawyers for the ACLU have argued that Division of Motor Vehicles employees do not consistently provide those credentials.

Karyn Rotker, one of the ACLU’s attorneys on the case, said there is no way to know why the court has not yet ruled.

“We’re surprised it’s taken this long,” she said.

Student voting cumbersome

Because of the voter ID law, “things have totally changed,” said Analiese Eicher, program director at One Wisconsin Now, the left-leaning advocacy group whose arm sued to overturn the law. The group often serves as a counterpoint to Gov. Scott Walker and Republicans who run the state Legislature.

Eicher described how, during her time as a UW-Madison student from 2006 to 2011, she and her roommates would walk to the polling places together so that one could vouch for the rest.

“You used to be able to corroborate someone’s address,” Eicher said, explaining that in the past, students who obtained a bill with their addresses on it could sign an affidavit stating their roommates resided at the same address.

The law no longer allows for a “corroborating witness” to provide proof of residency for voters.

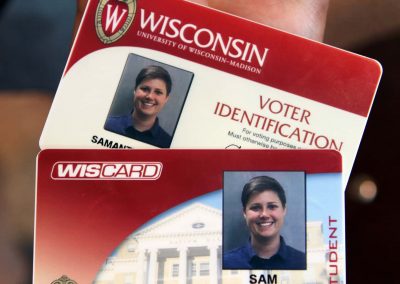

Since Eicher’s time in college, ID requirements for students have become much stricter. Of the 13 University of Wisconsin four-year campuses, only four provide campus-issued student IDs that are compliant for voting. The other nine campuses, including UW-Madison and UW-Milwaukee, failed to qualify under the guidelines set by the voter ID law.

That means out-of-state students and students with no driver’s licenses at those schools must get a second ID card from the university, which is valid for only two years, as well as a Voter Enrollment Verification letter proving they are enrolled in school.

These extra steps were by design: A former GOP staffer testified in 2016 that some Republican senators in a closed session were “giddy” about the prospect of voter ID suppressing votes by Milwaukee residents and college students, both of whom tend to vote Democratic.

Voter ID law was a “model bill”

According to Mary Bottari, the deputy director at the Center for Media and Democracy, the “echo effects” of voter ID laws from state to state were no accident — they were based on a “model bill” from the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC.

ALEC provides a meeting ground for corporations and special interests to create model bills for state lawmakers, who often lean ideologically to the right. An investigation by Bottari and CMD, a left-leaning government watchdog that publishes the ALEC Exposed website, found similarities among the voter ID bills introduced around the country.

“Each bill is slightly different,” said Bottari, “it’s not a cookie cutter bill. Each state did something slightly different to screw over certain groups of people. So, for instance, students were uniquely screwed in Wisconsin.”

Students in other states with voter ID laws also face obstacles. In Texas, voters who possess handgun license photo cards are permitted to use that as acceptable forms of identification, but University of Texas state-issued school ID cards are not accepted.

“We have to think really carefully about the barriers that are put into voting in an already-declining voter turnout reality that we live in,” said Brian Klaas, a fellow in comparative politics at the London School of Economics.

Klaas has acted as an adviser to U.S. political campaigns, NATO and the European Union on issues related to authoritarianism and democracy. He believes Wisconsin and other states should make it easier to vote, not harder. Such voter ID laws, Klaas said, are “really unfortunate for democracy,” because lower voter turnout can lead to less legitimacy for election results.

In the 2016 presidential election, Wisconsin’s overall voter turnout was 70.5 percent, the lowest in two decades.

Voting a ‘bad’ experience

Evans, who had trouble voting in the presidential election, had previously advocated for herself and other homeless, runaway or foster students at UW-Madison who did not have stable mailing addresses. In collaboration with the campus’ Working Class Student Union (WCSU), Evans created a program in which these students could have mail sent to the WCSU office — an address where Evans received her mail for four years.

“It was a kind of resource I had to create and ended up depending on, myself, to vote in the last presidential election,” she said. “And the experience of that … it was bad.”

She arrived at the polls that day to vote with her Wisconsin driver’s license, proof of enrollment at the university and mailing address. Poll workers hesitated, noting that her address, 333 East Campus Mall, was the same as the WCSU office and the polling place where she was trying to vote.

Even after explaining her living circumstances, Evans was told to sit to the side while poll workers called the Madison City Clerk’s office. Eventually, she was able to cast a ballot. She suspects other students may not have been able to exercise that privilege.

Hurdles go beyond college campuses

In Sauk City, Wisconsin, a town of around 3,400 residents about 30 miles north of the state Capitol in Madison, voters in the last presidential election without a proper form of identification could obtain free state ID cards at local Division of Motor Vehicles offices — but that office was only open every fifth Wednesday of every month — or just four days in 2016.

“I mean, that’s an absurd hurdle to clear,” said Matt Rothschild, executive director of the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, a nonpartisan political watchdog group. “(The voter ID law) made it harder for people to cast a ballot. Making it much harder to vote is about as anti-democratic as you can get.”

Gail Juszczak of Lake Mills, Wisconsin, said she believes the voter ID law is aimed squarely at people likely to vote Democratic.

“I think that the whole vote and the whole idea of changing this is to exclude certain people from voting,” said Juszczak, interviewed outside her polling place during the Aug. 14 partisan primary election. “And I think it’s definitely hurt the Democratic Party, particularly because more of the Democrats are people who aren’t as able to show identification as clearly, or elderly people or disabled people. So I think it’s definitely hurting some people.”

The state also initially did a poor job of explaining the changes to residents, said Anita Johnson, a Milwaukee resident who has been educating voters on their rights for 25 years.

“People are confused,” Johnson said. “Some people at the beginning thought that there was an actual voter ID card. There is no such thing as a voter ID card.”

While working with Citizen Action of Wisconsin in Milwaukee to educate the public on voting rights, in 2015, Johnson began working with VoteRiders, a national nonprofit organization specializing in helping people obtain proper identification to vote. Citizen Action is a progressive activist organization.

“A few years ago, we never had to show ID when we went to the polls to vote,” Johnson said. “You just went in, as long as you were a registered voter and said your name, your address, and you voted. Now, it’s a task. It should not be a task.”

VoteRiders services includes arranging transportation to local Division of Motor Vehicle offices, free legal assistance in obtaining proper documentation, and covering the costs of documents required for registering to vote such as birth certificates and Social Security cards.

Helping seniors vote

Johnson’s presentations on voting are often aimed at vulnerable communities such as the homeless and those lacking the foundational documentation required to vote. But Johnson, who said it has taken up to six months for people to get the proper identification, jokingly refers to the voter ID law in Wisconsin as an “equal opportunity law” because of it affects everyone.

That includes senior citizens, who may have moved into Wisconsin to be closer to family and might not be sure of just how the law works. If they do not have a state-issued driver’s license and do not know that they need another form of identification, “many don’t discover they have a problem until they try to vote,” said Gail Bliss, a senior liaison for the League of Women Voters in Dane County.

One fix for older voters in that situation is obtaining a permanent absentee ballot, which does not require a photo ID and provides automatic absentee ballots for future elections. Bliss called it the “saving grace” of Wisconsin’s voter ID legislation. Bliss said the league created flyers publicizing the service to pass out to Meals on Wheels recipients.

Still, many elderly voters are not aware of that option until after they are turned away from the polls, she said.

Kathleen Fullin is a Dane County League of Women Voters member who organizes contacts with provisional voters who fail to return to the polls with required identification to allow their votes to be counted. She said she remembers the case of a provisional voter who should have been allowed to vote — a senior citizen with a driver’s license that had expired since the last general election — but was barred from doing so.

“Her family had actually contacted the Wisconsin Elections Commission and knew she should be permitted to cast a regular ballot, but the chief inspector at her polling place would not permit it,” Fullin said in an email.

Said Johnson: “Voting should be one of the easiest things you can do. And it allows you to participate in democracy. So when you put up problems like the voter ID law, people say ‘Forget it, I’m not going to vote.’ ”

Effects of voter ID law debated

Challengers to the voter ID law had argued that hundreds of thousands of valid Wisconsin voters — many of them Hispanic, African-American and students — could be barred from casting ballots because of the identification requirement.

A UW-Madison study commissioned by Dane County Clerk Scott McDonell in 2017 tried to measure the effect. The study estimated that thousands of registered voters in Dane and Milwaukee counties were deterred or prevented from voting because of the photo ID requirement in the 2016 presidential election — a situation that more heavily affected low-income people and African-Americans. The survey was mailed to 2,400 registered voters; 293 were returned.

Based on the sampling weight, UW-Madison political science professor Kenneth Mayer concluded that between 7.8 and 15.5 percent of eligible voters in these two counties had been deterred from voting due to confusion over voter ID requirements or lack of proper identification. That equated to between 11,701 and 23,252 people, the study concluded.

Trump won Wisconsin by 22,748 votes.

Mayer’s conclusion was challenged by a free market, limited government legal group, which contended there was no proven linkage between the photo ID requirement and the election results. Will Flanders, research director at the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, said the study “pushed a narrative” of voter suppression but did not actually prove it.

Flanders said black and low-income voters who did not vote were “more likely to cite the lack of voter ID,” but the differences were not statistically significant. He also claimed the study suffered from a small sample size and, because of self-selection bias, the results were not representative.

“It is fundamentally misleading to say that all of those who claimed they did not vote because of the law could not do so,” Flanders wrote. “The most this survey can claim to prove is that the administration of the law could have been improved or that the candidates could have run better ground games.”

But, with the 2018 general election approaching, stories like Brooke Evans’ show how easily confusion about voting can jeopardize voting. If it were not for her own efforts to help homeless students, Evans said, she herself might not have been able to vote.

“I ended up relying on (activism) to access basic human rights, like the right to vote.”

Voter fraud? Studies contradict photo ID rationale

Voter impersonation — the reason voter ID laws were passed in the first place — has largely been debunked as a pervasive problem in U.S. elections, according to a summary of investigations and studies compiled by the Brennan Center for Justice. The law and policy institute out of New York University Law School focuses on campaign finance reform, mass incarceration and voting rights.

Former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder cited a Brennan Center study when speaking at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in March.

“The likelihood for a person to cast a fraudulent ballot is as likely as a person to get struck by lightning,” said Holder, who now serves as the chairman of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, which is pushing states to adopt nonpartisan processes for redrawing electoral districts.

“(Republicans) just can’t come up with the statistics that show that you have this problem of casting fraudulent ballots,” Holder said. “It’s clear that they are trying to rig the system. The president (Donald Trump) talked about during the campaign how the system was rigged. Well, I’m here to tell you, the biggest rigged system in this country is gerrymandering and voter ID laws.”

Earlier this year, Trump disbanded his voter fraud commission without making any findings. One of the commission members, Matthew Dunlap, Maine’s Democratic secretary of state, told NPR in August that the group never found evidence of Trump claims that millions of people had voted illegally in the 2016 election. He called voter fraud a “phantom menace.”

Brian Klaas, a fellow in comparative politics at the London School of Economics, finds that voter ID laws may be a “deliberate plan” to disproportionately disenfranchise minority voters, particularly Democrats, through incurring costs on voting, whether it be time or financial.

“It’s also the reason why you have so many lies, frankly, about voter fraud,” Klaas said. “Every single study on voter fraud has found that its a miniscule problem and almost always has non-nefarious intent.”

Before filing its 2015 federal lawsuit, One Wisconsin Institute filed open-records requests for all complaints of voter fraud from “every single legislator” who claimed to have received them, according to program director Analiese Eicher.

Of the 15 who had records, they consisted of unverified constituent complaints, news articles about the less than two dozen reported cases in Wisconsin since 2004 and a “widely discredited” anonymous report on alleged fraud in Milwaukee, the group said.

Fifty lawmakers said they had no responsive records. Eicher said lawmakers “had to swear under oath in our lawsuit that voter fraud didn’t exist — which was fun watching that happen.”

Nevertheless, the myth of widespread voter fraud persists, especially among Republicans, according to the June PRRI/The Atlantic survey funded by the Joyce Foundation, which also supports the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism’s coverage of democracy issues. It found 52 percent of Republicans and 31 percent of Democrats believe a major problem with U.S. elections is “people casting votes who are not eligible to vote.”

Cameron Smith, with contributions by Dee J. Hall and Madeline Heim

Dee J. Hall, Coburn Dukehart, and Belle Lin

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.