City and law enforcement leaders in Kenosha unanimously endorsed the use of body cameras in 2017 as a way to increase police accountability and collect evidence at scenes of domestic violence, among other benefits. But since then, they have balked at the price tag, raised policy concerns, and put off implementation.

The delays meant that officers who were on the scene of Sunday’s shooting of Jacob Blake while responding to a domestic call were not equipped with technology that could give their perspective on an incident that has roiled the nation.

Instead, the public has only seen video captured by a neighbor that shows one or more officers shooting Blake, 29, in the back several times as the Black man walked away from them, opened his SUV’s driver-side door and leaned into the vehicle. It does not show what happened before or after the shooting like body camera footage would.

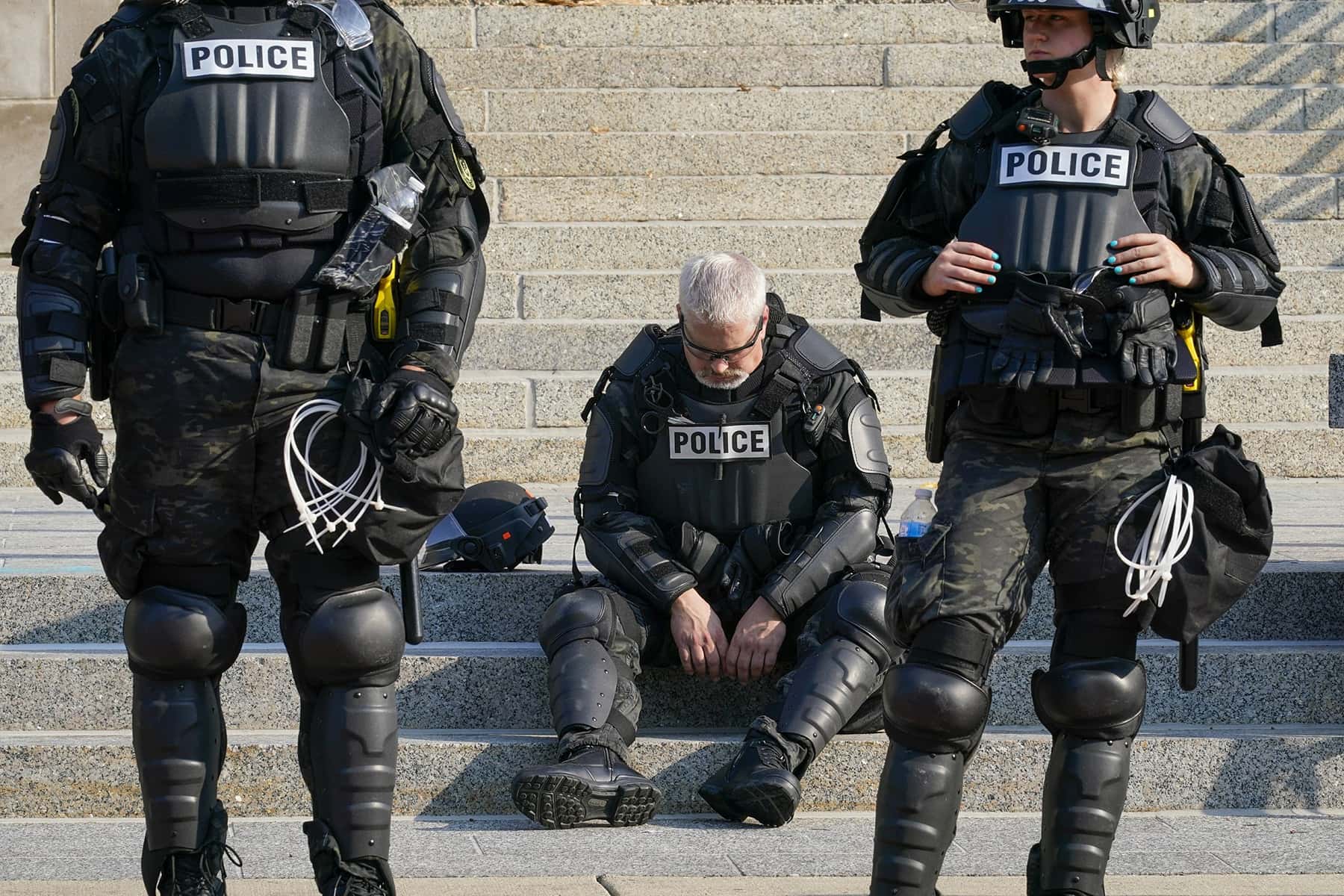

The shooting left Blake paralyzed from the waist down and it sparked civil unrest in Kenosha, a city of 100,000 people between Milwaukee and Chicago. But it also shined a light on Kenosha’s delays in equipping its roughly 200 police officers with body-worn cameras, which has made the city fall behind many of its neighbors and similar-sized peers.

“This is a tragedy. But at least some good could come from this if this is finally the incident where Kenosha says, ‘we’ve got to get body cameras on these cops right away’,” said Kevin Mathewson, a former member of the common council.

Kenosha Mayor John Antaramian confirmed on August 24 that current plans called for the city to buy them in 2022 — more than five years after he endorsed their adoption. Kenosha officers do have cameras in their squad cars, but it is unclear whether any captured the shooting.

Mathewson pushed the city to buy cameras during his tenure on the council from 2012 to 2017, saying he saw them as a tool to remove bad police officers from the department after a series of troubling use-of-force and misconduct incidents. Body cameras became particularly popular nationwide as a way to improve policing after the 2014 fatal shooting of Michael Brown, a Black 18-year-old, by a white officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

Mathewson recalled proposing a budget amendment to buy the equipment in early 2017 and hitting resistance from the mayor, police chief and other council members, who argued that would be unwise without clear state regulations governing their use.

By then, Kenosha had already fallen behind most other midsized police departments nationwide that were moving forward with body camera programs. By 2016, 56% of departments with between 100 and 250 officers had acquired them, and most had some officers wearing them, according to a 2018 U.S. Department of Justice study. Their use is believed to have increased substantially since then, although funding challenges remain.

Instead of providing the money immediately, Kenosha’s council passed a unanimous resolution in March 2017 recommending their use, listing their numerous benefits and noting that the police chief, the district attorney and the mayor were in favor. But the resolution said that their adoption in Kenosha hinged on the state providing guidance to departments on usage, storage, public records and privacy issues.

Governor Tony Evers signed a law in February outlining body camera regulations for police departments. The law requires footage to be retained for 120 days at minimum — longer in certain cases — and says recordings are generally subject to Wisconsin’s open records law.

Kenosha initially planned to buy the cameras this year, but funding shortfalls and technological concerns prompted the city to push that back to 2022, said Rocco LaMacchia, chairman of the council’s public safety committee.

“We have moved it back so many times,” he said. “I got a feeling this is going to move up on the ladder really fast because of what’s going on around the United States right now. Body cameras are a necessity. There’s no doubt about it.”

Of the Blake shooting, he said, “The body camera footage on this one would have told right from wrong right away.”

The city’s current plans call for purchasing 175 Axon body cameras from Taser International and a five-year evidence storage and maintenance plan in 2022. After the first year, the city would incur an estimated $145,000 cost annually for using Evidence.com to store video evidence.

Michael Bell Sr. has been advocating for police reforms since officers in Kenosha fatally shot his 21-year-old son, Michael Bell Jr., in 2004. He has had success at the state level, helping in 2014 to push through a law requiring outside investigation when people die in the hands of law enforcement. But the retired U.S. Air Force lieutenant colonel said officials in Kenosha have consistently failed to act on years of calls for police body cameras, which he likened to the “black box” on an airplane.

“I feel that there has been no movement,” he said. “Every time they put body camera funding into the budget it’s been kicked downstream.”

An increasing number of studies suggest the cameras do not change how often officers use force. In Milwaukee, officers used slightly less force after starting to wear cameras at first but then returned quickly to normal levels, said Daniel Lawrence, a researcher at the Urban Institute in Washington DC, who studied their adoption.

Complaints against officers dropped significantly, but it was unclear whether that was due to improved interactions, citizens’ fears of filing false claims or both, he said.

Body camera footage of the Blake shooting would have been important, but video from squad cars or other sources may be able to provide key perspectives for investigators, Lawrence said.

“The cameras themselves can provide a lot of insight into an officer’s mindset before and after a shooting, but they may not be the crucial piece of evidence that makes or breaks a case,” he said.

Ryаn J. Fоlеy, with Jаkе Blеіbеrg

Mоrry Gаsh