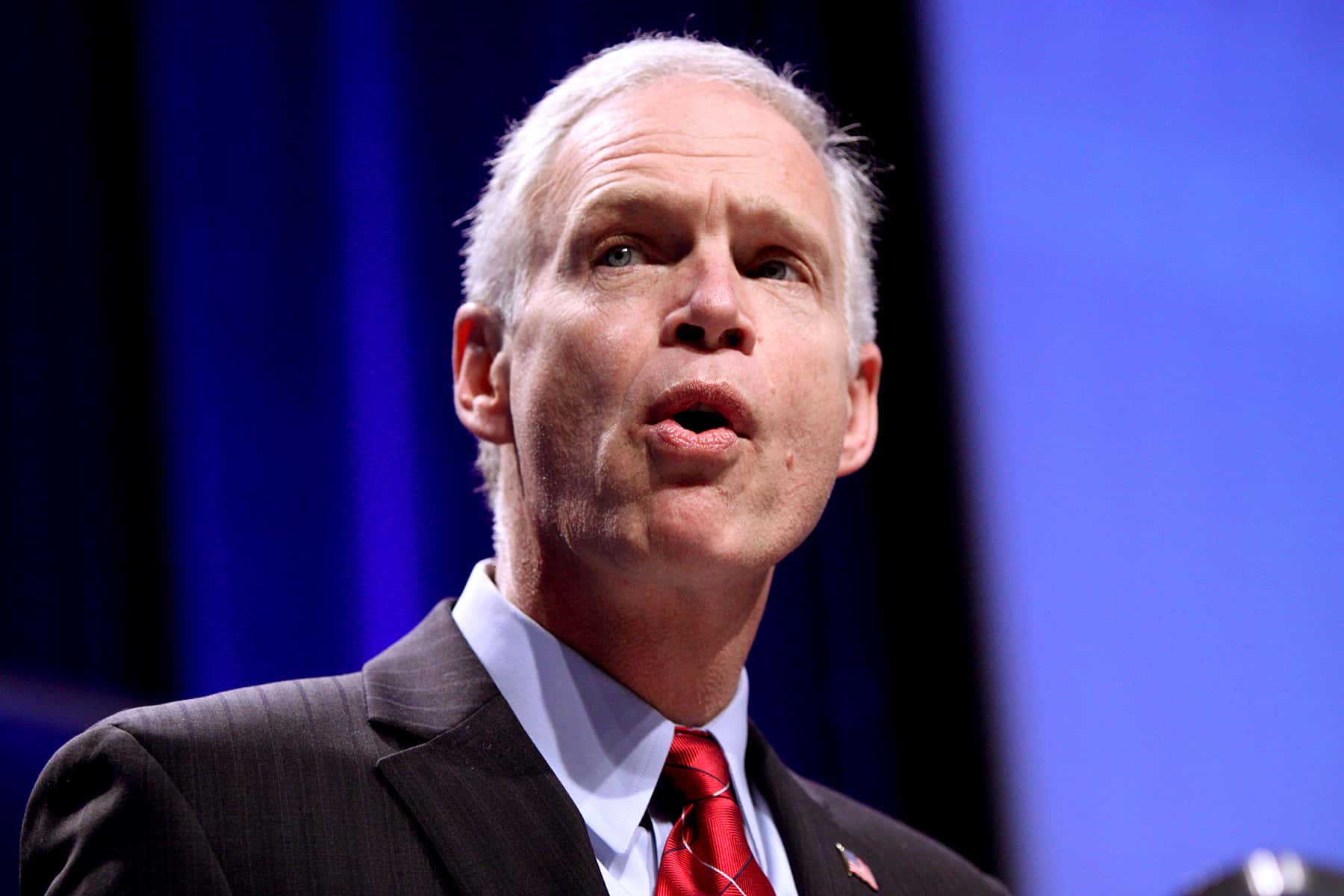

Photo by Gage Skidmore and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Several times this summer, Senator Ron Johnson (R-Wisconsin) has defended his opposition to any new Congressional relief from the economic ravages of COVID-19 by asserting that financial help for people who are out of work from the pandemic keeps them from going back to work.

He is not alone. Almost since a federal supplement of $600 a week for workers who had lost hours or been laid off took effect in April, claims have circulated that workers were turning down return-to-work calls from their employers.

Johnson reiterated that message recently, telling Green Bay television station WLUK, “We need to certainly … get rid of those incentives for people to stay on unemployment because they make more money on unemployment than actually going back to work.”

Johnson spoke in defense of his opposition to extending the federal $600 Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) supplement, which was added on to state unemployment compensation under the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act that Congress passed in March.

The supplement expired July 25. While the House of Representatives passed legislation in May extending the $600 through early next year, it has stalled in the Senate as the two houses of Congress have so far deadlocked on any new COVID-19 relief package.

President Donald Trump signed a questionable memorandum on August 8 replacing the $600 benefit with a $300 weekly supplement plus $100 from the states. But Governor Tony Evers told reporters on August 13 that exactly what the terms of the memo are “has changed somewhat — it seems a lot, frankly” since Trump signed it.

While the governor and his staff are still reviewing the memo, Evers said, “I think this could be more readily and more logically solved if the President and the Congress got their act together and passed similar legislation” to the measure that had expired.

Too generous?

Inquiries over several weeks have yet to yield any substantive evidence for the claim, by Johnson and others, that the higher jobless pay was discouraging people from going back to work.

“It’s a talking point by Senator Johnson, but there’s no factual basis to it,” said Victor Forberger, a Madison lawyer who represents people seeking unemployment compensation. “The only reason people don’t want to work is they’re scared of COVID and they don’t want to die.”

Moreover, the regulations that govern unemployment insurance (UI) make it unlikely that people routinely turn down a return-to-work call from employers in order to keep collecting jobless pay — both regular state unemployment compensation and the federal supplement.

Wisconsin laws governing unemployment insurance and compensation generally require that laid-off workers who are offered a chance to go back to their jobs must accept the offer — and if they don’t they will usually lose their jobless pay.

The state Department of Workforce Development (DWD) posted a web page focusing on return-to-work questions after the Wisconsin Supreme Court ended Evers’ Safer at Home order on May 13. Hypothetical questions reflect both employer and employee perspectives. One asks: “My employer is reopening but I don’t plan to return to work, am I eligible for unemployment?”

DWD’s answer: “Unemployment benefits are available to individuals who are totally or partially unemployed due to no fault of their own. In this example, the individual—not the employer—is choosing not to work and, therefore, would be ineligible.” The answer adds a disclaimer, however, that “the facts of each circumstance are important,” and might require an investigation to settle the question of eligibility.

The same question is posed from the employer’s perspective: “If an employee decides not to return to work when the business reopens, are they eligible for unemployment?” DWD’s Answer: “In most cases, no. Unemployment benefits are available to individuals who are totally or partially unemployed due to no fault of their own. In this example, the individual—not the employer—is choosing not to work and, therefore, would be ineligible.” Again, though, it offers the disclaimer that based on specific circumstances, an investigation would be necessary to determine eligibility.

‘That would end your eligibility’

Interviewed in late July, DWD Secretary Caleb Frostman said that he has heard vague claims outside the agency about workers turning down return-to-work offers because they were getting more money from unemployment. “I get really skeptical when I hear that,” he said. “Under current Wisconsin law, if you refuse work, under many circumstances that would make you ineligible.”

According to a DWD spokesman on August 13, the department has no readily available data to show how many people have had their unemployment terminated for declining a return-to work offer or a job offer in the spring or summer of 2020 during the pandemic. In his July interview, Frostman said that he had recently been told that “there were a really small number of holds [on unemployment claims] for work refusal.”

Frostman observed that “there are different nuances [in] what circumstances you can refuse work under,” but added: “Generally speaking, if you turn down the work that would end your eligibility for UI.”

Business lobbyists have been asked for examples of employers who had been turned down by workers content to stay home and collect unemployment. Only one reported hearing such complaints from organization members, but said efforts to persuade any to go public were unsuccessful.

On August 13, Johnson’s office was asked to supply substantiation for the senator’s assertion about unemployment compensation as an incentive to stay home rather than return to work, particularly in light of the restrictions in Wisconsin law, which are common around the country. In a telephone call, a staff member directed that an email be sent to another staff member with the question. There was no response to the email inquiry. Meanwhile, several studies have found no evidence for the claims.

A Yale University report published July 27 found no connection between how much people were receiving on unemployment and their return to work. “Workers who experienced larger increases in UI generosity did not experience larger declines in employment when the benefits expansion went into effect,” the report states. “Additionally, we find that workers facing larger expansions in UI benefits have returned to their previous jobs over time at similar rates as others.”

Another report, published July 30 by a team from the University of Pennsylvania, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the job listing website Glassdoor Inc., found that “employers did not experience greater difficulty finding applicants for their vacancies after the CARES Act, despite the large increase in unemployment benefits.”

Stimulating the economy

Writing on the website The Conversation, Daniel Salkever of the University of Maryland Baltimore County calculates that as many as 56% of U.S. workers might collect more in jobless payments (when the federal supplement is included) than they do from working. But, he adds, the rules requiring people to give up their unemployment if they turn down a return-to-work request led him to conclude that claims that the supplement dissuades people from working were “unpersuasive.” Jobs, for example, may provide benefits such as health insurance that unemployment does not — adding to the incentive to return to work.

In his article Salkever points out that when it was originally instituted during the Great Depression, unemployment compensation wasn’t just intended to tide jobless people over. “Consumer spending makes up more than 70% of the economy, and most of those who receive the benefit will spend it quickly,” he writes. “This powerful and ongoing jolt would help revive the economy – or at least keep it alive – as well as offset worries that economic inequality will soar as a result of the pandemic.”

Frostman makes the same point. In the July interview he said, “We’ve tried to point out to chambers [of commerce] and employers that the $600-a-week program was really meant to be a stimulus.”

“It was meant to keep not only those families afloat, but also the state’s economy — to keep people in their homes, paying rent, paying their mortgage, buying groceries, stimulating the economy through their normal levels of consumer spending.”

Originally published on the Wisconsin Examiner as Why jobless pay didn’t keep people home instead of working

Donate: Wisconsin Examiner

Help spread Wisconsin news, relentless reporting, unheard voices, and untold stories. Make a difference with a tax-deductible contribution to the Wisconsin Examiner