By Geoffrey Jones and Sudev Sheth; Isidor Straus Professor of Business History, Harvard Business School; Senior Lecturer, The Lauder Institute, University of Pennsylvania

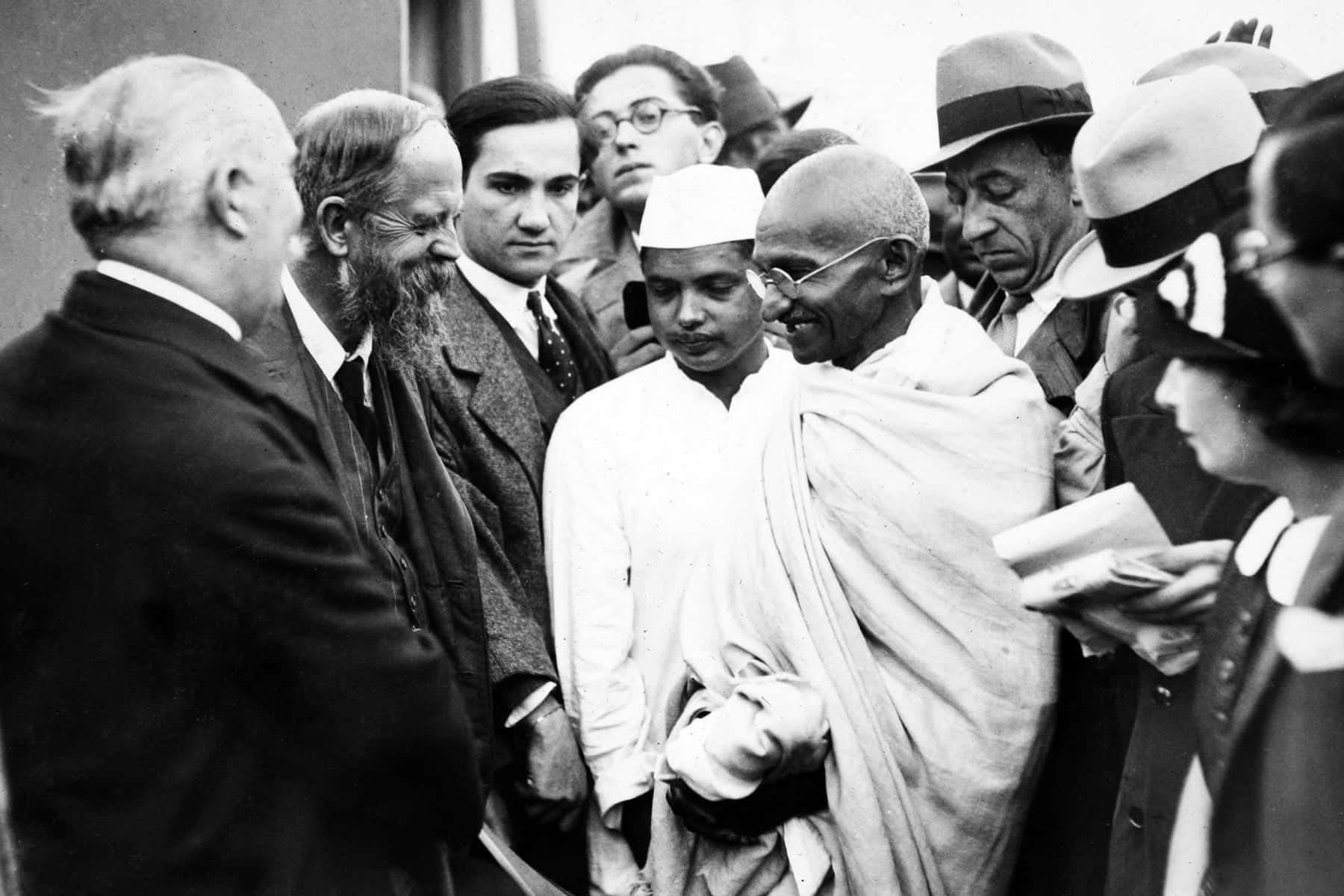

Mahatma Gandhi is celebrated across the globe as an idealist who used civil disobedience to frustrate and overthrow British colonialists in India.

The popularity of his nonviolent teachings – which inspired civil rights activists such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela – has obscured another important facet of his teachings: the proper role of business in society. Gandhi argued that companies should act as trusteeships, valuing social responsibility alongside profits, a view recently echoed by the Business Roundtable.

His views on the purpose of a company have inspired generations of Indian CEOs to build more sustainable businesses. As scholars of global business history, we believe his message should also resonate with corporate executives and entrepreneurs around the world.

Shaped by globalization

Born in British-ruled India on Oct. 2, 1869, Mohandas K. Gandhi was the product of an increasingly global age. Our research into Gandhi’s early life and writings suggests his views were radically shaped by the unprecedented opportunities that steamships, railroads and the telegraph provided. The growing ease of travel, the circulation of print media and the increase in trade routes – the hallmark of the first wave of globalization from 1840 to 1929 – impressed upon Gandhi the myriad of challenges facing society.

These included vast inequality between the rich West and other parts of the world, growing disparities within societies, racial tension and the crippling effects of colonialism and imperialism. It was a world of winners and losers, and Gandhi, although born into an affluent family, dedicated his life to standing up for those without status.

The horrors of industrialization

Gandhi studied law in London, where he encountered the works of radical European and American philosophers such as Leo Tolstoy, Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and John Ruskin – transcendentalists who advocated intuition over logic.

Ruskin’s moving discussion of the ecological horrors of industrialization, in particular, caught Gandhi’s attention and led him to translate Ruskin’s book “Unto This Last” into his native Gujarati. In 1893, Gandhi took up his first job as a barrister in the British colony of South Africa. It was here, not in India, where Gandhi forged his radical political and ethical ideas about business.

His first public speech ever was to a group of ethnic Indian businesspeople in Pretoria. As Gandhi recalls in his candid autobiography “The Story of My Experiments with Truth”:

“I went fairly prepared with my subject, which was about observing truthfulness in business. I had always heard the merchants say that truth was not possible in business. I did not think so then, nor do I now.”

Gandhi returned to British-occupied India in 1915 and continued to develop his ideas on the role of business in society by talking to prominent business leaders such as Sir Ratanji Tata, G.D. Birla and Jamnalal Bajaj. Today, the children and grandchildren of these early Gandhi disciples continue to lead their family businesses as some of not only India’s but the world’s most recognized conglomerates.

The role of business

Gandhi’s views of what trusteeship really means were expressed in great detail in his widely popular Harijan, a weekly periodical that highlighted social and economic problems across India. Our study of Harijan’s archive from 1933 to 1955 helped us identify four key components of what trusteeship meant for Gandhi:

- a long-term vision beyond one generation is necessary to build truly sustainable enterprises

- companies must build reputations that foster trust across transactions and with all sections of society

- business enterprise must focus on creating value for communities

- while Gandhi saw the value of private enterprise, he believed the wealth a company creates belongs to society, not just the owner.

Gandhi was murdered in 1948, just after India secured independence. However, his ideas have continued to resonate deeply with some of India’s leading companies. Interviews conducted for Harvard Business School’s oral history archive turned up surprising evidence in recent decades of Gandhi’s role in guiding modern companies in a variety of countries toward more sustainable business practices.

“We have to take care of all stakeholders,” says billionaire Rahul Bajaj, chairman of one of India’s oldest and largest conglomerates, recalling his grandfather’s association with Gandhi. “You can’t produce a bad-quality and high-cost product and then say, I go to the temple and pray, or that I do charity; that’s no good and that won’t last, because that won’t be a sustainable company.”

Anil Jain, vice chairman and CEO of the second largest micro-irrigation company in the world, recalls:

“My father was greatly influenced by Mahatma Gandhi who believed in simplicity – he believed that the real India lives in villages, and unless villages are transformed to become much better than how they are, India cannot really move forward as a country.”

What would Gandhi say

Gandhi’s views were constantly evolving in dialogue with the business community, and this is one reason why they remain so relevant today. Imagine a Gandhian perspective on today’s tech companies. He would perhaps ask proponents of self-driving cars to consider the impact on the lives of hundreds of thousands of cab drivers around the world. He would ask proponents of e-commerce to consider the impact on local communities and climate change. And he would ask shareholders whether closing factories to maximize their dividends was worth making communities unsustainable.

Gandhi did not have had all the answers, but in our opinion he was always asking the right questions. For today’s business leaders and budding entrepreneurs, his wise words on trusteeship are a good place to start.

Lee Matz and James A. Mills

Originally published on The Conversation as What Gandhi believed is the purpose of a corporation

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.