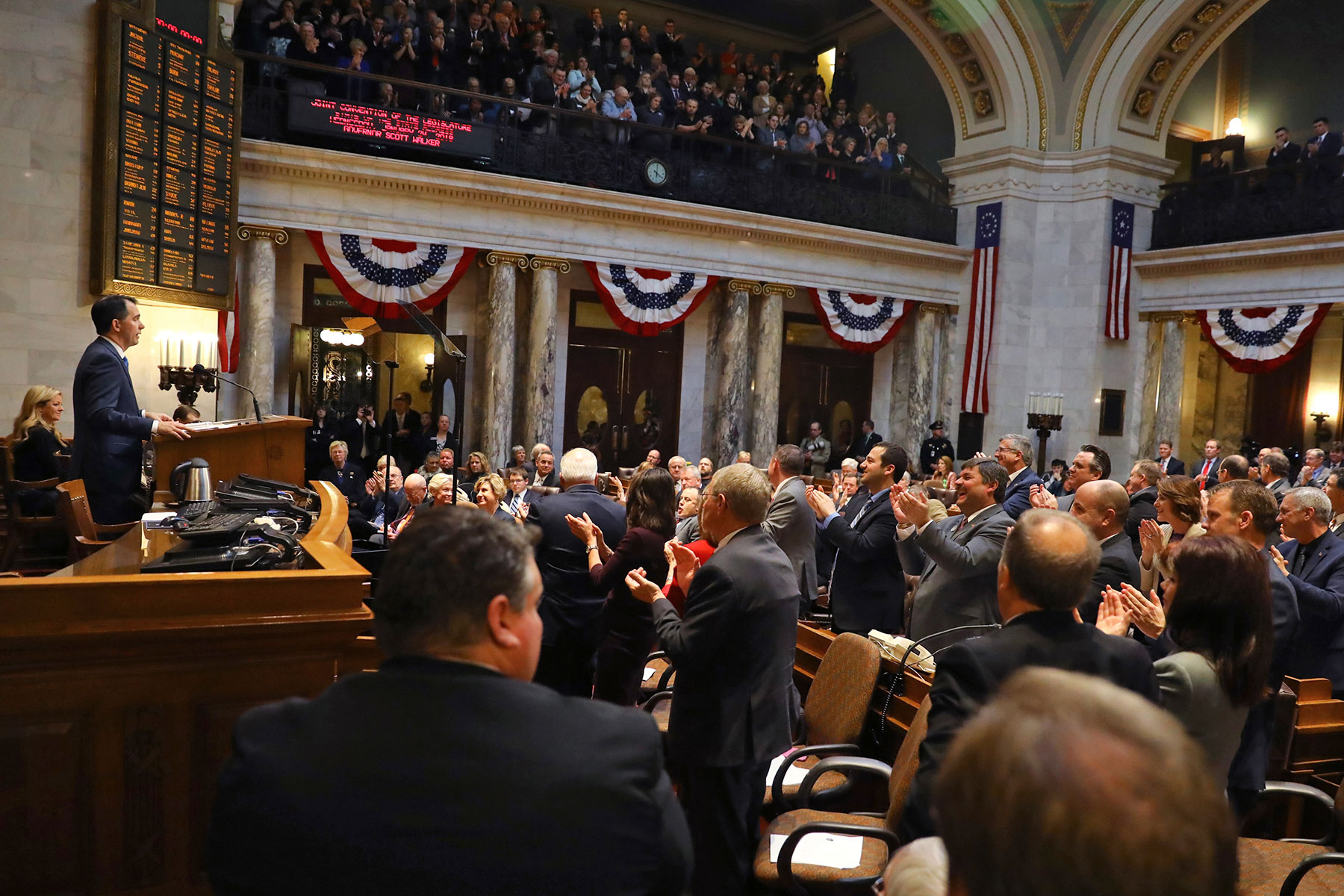

The length of time bills were deliberated dropped significantly soon after Governor Scott Walker and Republican legislators took control in 2011, diminishing the public’s opportunities to influence lawmaking, records and interviews show.

An analysis of all bills enacted into state law over the past two decades shows an overall decline in deliberation time — with the most dramatic drop happening just after Walker took office.

In Walker’s first two years in office, average deliberation time was 119 days, compared to a 20-year average of 164 days. During that 2011-12 session, one out of every four bills, including some of the Republicans’ most sweeping and controversial legislation, was passed within two months of introduction.

In comparison, in the 1997-98 session under Governor Tommy Thompson, it took an average of 227 days for a bill to be introduced, aired in public hearings, passed by the Assembly and Senate and signed into law. Republicans controlled the governor’s office and Senate at the beginning of that session, adding control of the Assembly in 1998.

By the 2017-18 session, when Republicans controlled both chambers of the Legislature and the governor’s office, the deliberation time averaged 162 days — close to the 20-year average but well below the levels seen in the pre-Walker years.

Among the bills approved in Walker’s first session was Wisconsin’s 2011 redistricting plan, which the U.S. Supreme Court recently kicked back down to the court that had overturned it. After being crafted in secret by Republicans, it was approved by the Legislature in 29 days.

Act 10, the law that stripped collective bargaining rights from most public workers in Wisconsin, was approved in 24 days. Walker’s goal with that bill, he conceded privately, was to “drop the bomb” on organized labor. Crowds estimated at up to 100,000 people showed up at the Capitol to protest that 2011 measure. It has been credited with cutting the ability of unions to support Democratic candidates in Wisconsin.

The Center used the 48 days from introduction to enactment for the massive Foxconn corporate subsidy deal in 2017 as a benchmark for fast-tracking. The analysis showed that 11.2 percent of legislation was fast-tracked, passing in 48 days or less, over the past two decades. Routine ratifications of already-negotiated labor contracts were excluded from the analysis. In the first session of Walker’s first term, the proportion of fast-tracked bills shot up to 26 percent.

West Bend businessman and thought leader John Torinus, who voted for Walker for governor three times and contributed to his 2010 campaign, has dubbed the strategy “government by surprise.”

Four experts on legislation and Congress said they are unaware of a similar analysis of deliberation speed on the state or national level, so it is unclear how the approval times in Wisconsin compare to those of other states.

Vinehout: Fast bills ‘bad for democracy’

Since that first chaotic session under Walker, the Legislature has spent more time deliberating on legislation, the Center’s analysis showed.

But some of the most contentious measures in recent years continue to be fast-tracked, including the 2017 vote authorizing the $3.2 billion state taxpayer subsidy to electronics manufacturer Foxconn and 2015’s so-called Right to Work Law, which bans labor unions from collecting dues from any workers who refuse to pay them.

The speed with which bills pass through the Wisconsin Legislature can be an indicator of whether the public’s voice in shaping public policy is being heard.

“I think it’s a symptom of the legislative process becoming less participatory,” said Barry Burden, a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and director of the Elections Research Center. “We see more examples … of bills being sprung very quickly without members knowing they’re coming, without the public knowing, and hearings being announced very quickly without lots of notice.”

State Sen. Kathleen Vinehout, D-Alma, has been outspoken about bills that move too quickly. She uses a colorful metaphor to illustrate the dangers.

“I think of legislation like fish,” said Vinehout, who ran unsuccessfully in the Democratic primary for governor. “It needs to be opened up and set on the table in the kitchen and have the sunshine on it, and we need to see if it smells. Legislation that moves too fast and too dark is almost always legislation that is bad for democracy.”

The group GovTrack.us, which tracks the U.S. Congress and aims to help Americans participate in national legislation, was asked whether measuring speed of bill approval could shed light on the strength of democracy. In a statement, the group, which is politically independent and self-supporting through advertising and crowdfunding, said “reasonable people could disagree” about whether quickly passed bills can be used to assess the health of a democracy.

Burden said some important legislation on the federal level is jammed through very quickly, with little time for the public or even members of Congress to read the bills. The minority party is often left out of the deliberation, he said.

“Congress introduces many more bills that never become law, but the ones that do tend to be prioritized by the party leadership and pushed through very quickly,” Burden said. “Sometimes they go around committees altogether, and there are no hearings, no deliberative process at all.”

Bills speed up under GOP control

In Wisconsin, the most dramatic increase in the speed of legislation came when the Legislature and governor’s office flipped from Democratic to Republican control in 2011. The data show that the average time from bill introduction to the governor’s signature dropped by 40 days — 25 percent — compared to the 2009-10 session under Democratic Governor Jim Doyle.

Rick Esenberg, the founder and current president and general counsel of the conservative Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, said one reason for faster passage of legislation could be the style of the current legislative leaders, Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald, R-Juneau, and Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester.

“It certainly is my impression that a lot of times, leadership wants to move really quickly on bills,” Esenberg said. “If you want to be heard on something, sometimes you have to gear up and you’ve got to get your perspective out there really quickly because the thing moves so fast.”

While saying he is unsure why speed has increased during the past two decades, Esenberg acknowledged fast-tracking can mute some voices.

“I do think that the downside of that is that you sacrifice something in the deliberative process,” Esenberg said.

Vinehout said some bills come from the Republican majority so quickly that she is not even sure what they do — and some of them involve “very big changes” to the economy.

“The idea I have seen in the leadership now is that they … want to move things so fast so that we don’t have time to thoroughly do the homework, we don’t have time to write the amendments, and most importantly, we don’t have time to understand what the bill does,” Vinehout said.

The Center sent emails to the four top legislative leaders — Fitzgerald, Vos, Assembly Minority Leader Gordon Hintz, D-Oshkosh, and Senate Minority Leader Jennifer Shilling, D-La Crosse, to present its analysis and ask whether fast-tracking and shorter deliberation times are good for democracy. Fitzgerald’s office did not respond to three emails seeking comment.

“Republican politicians are cutting out the public and shifting more power to special interest lobbyists and national conservative groups like ALEC (American Legislative Exchange Council),” Shilling said. “It’s become standard practice now for Republicans to meet with their donors and corporate lobbyists behind closed doors, write a bill in secret, and then pass it in a matter of days without any public input. It’s a major shift away from the level of transparency and accountability that citizens and taxpayers expect from their government.

“This is how bad bills become law,” she said.

The Center, which is independent, nonpartisan and nonprofit, analyzed deliberation times to measure the opportunity the public has to weigh in on legislation and whether that has changed over time.

Vos, however, criticized the Center’s analysis as a “politically-motivated and superficial (study) that shows a lack of understanding of the complexity of the legislative process.”

Said Vos: “The Legislature has approved bills in an efficient, effective and transparent manner. This flawed study doesn’t take into account the types of bills being approved, the percentage of bills that don’t become law (roughly 75 percent are only reviewed and don’t advance), the legislative session calendar, any national comparisons (many legislatures only meet for 120 days) or changes in the chamber rules over the last 20 years.”

UW-Madison political science professor David Canon raised some of the same issues, saying that such an analysis ideally would examine whether there was unified or divided control of government and the significance of the legislation. Canon said that the speed with which legislation passes is a better indicator of whether there is gridlock than whether a democracy is healthy.

Vos also said the analysis fails to take into account bipartisan agreements struck in recent years that made floor debate in the Wisconsin Assembly more efficient and predictable and curbed lengthy recesses for partisan caucusing.

He pointed to a 2017 study by the nonpartisan Legislative Reference Bureau that the agreements led to “less chaotic floor days, negotiated time limits for debate, and increased opportunities for citizens to observe and follow Assembly proceedings.”

However, those agreements were put in place beginning in 2013 — after the sharp uptick in fast-tracking that occurred when Walker first took office.

Vos’ Democratic counterpart, Hintz, said these procedural changes focus primarily on the final floor debate before a bill is passed and would have negligible effect on the overall length of deliberation time.

Hintz added that the Center’s analysis affirms his own experience. He said fast-tracking was used extensively at the beginning of Walker’s tenure for bills that helped Republicans gain a political advantage, including redistricting, voter ID and Act 10.

“Some of the bills that have been the most controversial, where the benefit to the public is questionable, have moved the fastest,” Hintz said.

The problem is exacerbated, he said, by the shrinking number of news reporters to keep the public informed.

“Part of the story has to be the declining oversight and coverage of the Legislature … and fast-tracking makes it even worse,” Hintz said. “It’s harder than ever for most people to follow what’s happening in government, which means less accountability.”

Walker spokeswoman Amy Hasenberg said the governor needed to act quickly to solve numerous problems when he first took office, including a multibillion-dollar deficit, “double-digit tax increases and record job losses.”

“Normally, people criticize the government for moving too slowly…this must be the first piece I’ve seen criticizing one for getting too much done for the people it serves,” Hasenberg said.

“Wisconsin voted for Governor Walker and the Republican Legislature to get things done and that’s exactly what they did,” she said. “Wisconsin is in better shape today in virtually every measurable way thanks to the bold action of Governor Walker and the Republican Legislature.”

‘Model’ bills hasten passage

Jacob Stampen, an emeritus professor of educational leadership and policy analysis at UW-Madison who has tracked legislative voting patterns in the state, said one factor is ALEC, which has been tied to at least three dozen bills and budget measures in Wisconsin since Walker took office.

ALEC is a national organization of state lawmakers, most of them conservatives, who meet with corporate interests to craft business-friendly legislation in the form of “model bills” that can be quickly introduced in numerous states. The group describes itself as dedicated to the principles of limited government, free markets and federalism.

ALEC Exposed, a website by the Center for Media and Democracy, a Madison-based liberal government watchdog, has published hundreds of model bills propagated by ALEC. Such bills are crafted by politicians and corporate representatives meeting behind closed doors.

“Sometimes legislators say ‘It’s my own original idea.’ They can’t do that anymore because we published 800 model bills in 2011, and we still track their new bills,” said Mary Bottari, deputy director of the Center for Media and Democracy.

Burden also cites the sharing of information across state lines within parties as a factor for bills moving faster through the Legislature. Burden noted that model bills can come from a variety of nonpartisan sources, including the Council of State Governments and the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Stampen said when Walker was elected, and both legislative houses were controlled by Republicans, the GOP was ready with a series of ALEC bills.

“So that increase (in speed) in that year was all these bills that were ready to vote on that were all model legislation from the American Legislative Exchange Council,” Stampen said.

“They behaved as if they had a large majority and they could pass anything they wanted to,” Stampen said, adding that the variety of the fast-tracked legislation was “breathtaking.”

The so-called Right to Work Law, 2015 Wisconsin Act 1, a model fast-tracked bill, was introduced on Feb. 23, 2015 by Fitzgerald’s Senate Committee on Organization. It passed both houses in a specially called session and was signed into law 14 days later. The two-page law ended the ability of unions to require all workers covered by union contracts to pay dues — seen as another blow to the power of unions, which tended to support Democrats.

As the bill sped toward approval, the Rev. Cindy Crane with the Lutheran Office for Public Policy in Wisconsin called for a 90-day delay saying, “The reality is that the Legislature and the people of this state do not have enough information.”

“Rushing this legislation through in an extraordinary session is a slap in the face to our democracy,” Phil Neuenfeldt, president of the Wisconsin AFL-CIO, told the Wisconsin State Journal.

Fast-tracking legislation is not new. For example, Doyle and fellow majority Democrats in the Assembly and Senate rammed through a controversial statewide indoor smoking ban in May 2009, although it did enjoy some Republican support.

But the Center’s analysis indicates that fast-tracking was more heavily used by the GOP-run Legislature in the 2011-12 session than it had been under the Doyle administration.

Although less used in the 2017-18 session, fast-tracking continues. The Foxconn deal, or Wisconsin Act 58, took less than two months from its initial proposal in the Assembly to its enactment. The 13-page bill obligates Wisconsin taxpayers to an estimated $3.2 billion in state incentives plus an expedited $408 million upgrade of Interstate 94, one of the largest public subsidies of a private company ever in the United States. It was introduced at Walker’s request.

“We had very little notice that the Foxconn deal was going to happen, and when we got the actual bill, it was very vague, there was a lot of unknowns,” said Vinehout, who voted against it along with a majority of Democrats and a few Republicans.

Partisanship key to fast-tracking

To gain insights into the health of Wisconsin’s democracy, Stampen examined voting behavior in the Legislature in 1965-66 and from 2003 through 2016. A paper by Stampen examined personal characteristics of legislators and their voting behavior between the mid-60s and 2005-06.

The characteristics that he looked at included age, ethnicity, gender, education, occupational background and birthplace. But in the end, the most important factor that affected voting behavior was the legislator’s party.

Stampen found that in both houses in the 1965-66 legislative session, lawmakers from both parties displayed more variation in their voting behavior. But 40 years later, Senate and Assembly Republicans who ran the Legislature voted as a bloc on contested bills 95 percent of the time.

Burden agreed that such bloc voting can lead to greater speed.

“Increasingly the parties have been more ideologically coherent, and so they have less dissent — even within their own party,” Burden said.

“There used to be more frequent negotiations between members of both parties, and so that prolonged the process of dealing with legislation. Now there is very little conversation across the aisle.”

Teodor Teofilov, Dee J. Hall, and Pawan Naidu

Coburn Dukehart and Michael P. King

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.