By Liz Sharples, Senior Teaching Fellow (Tourism), University of Portsmouth

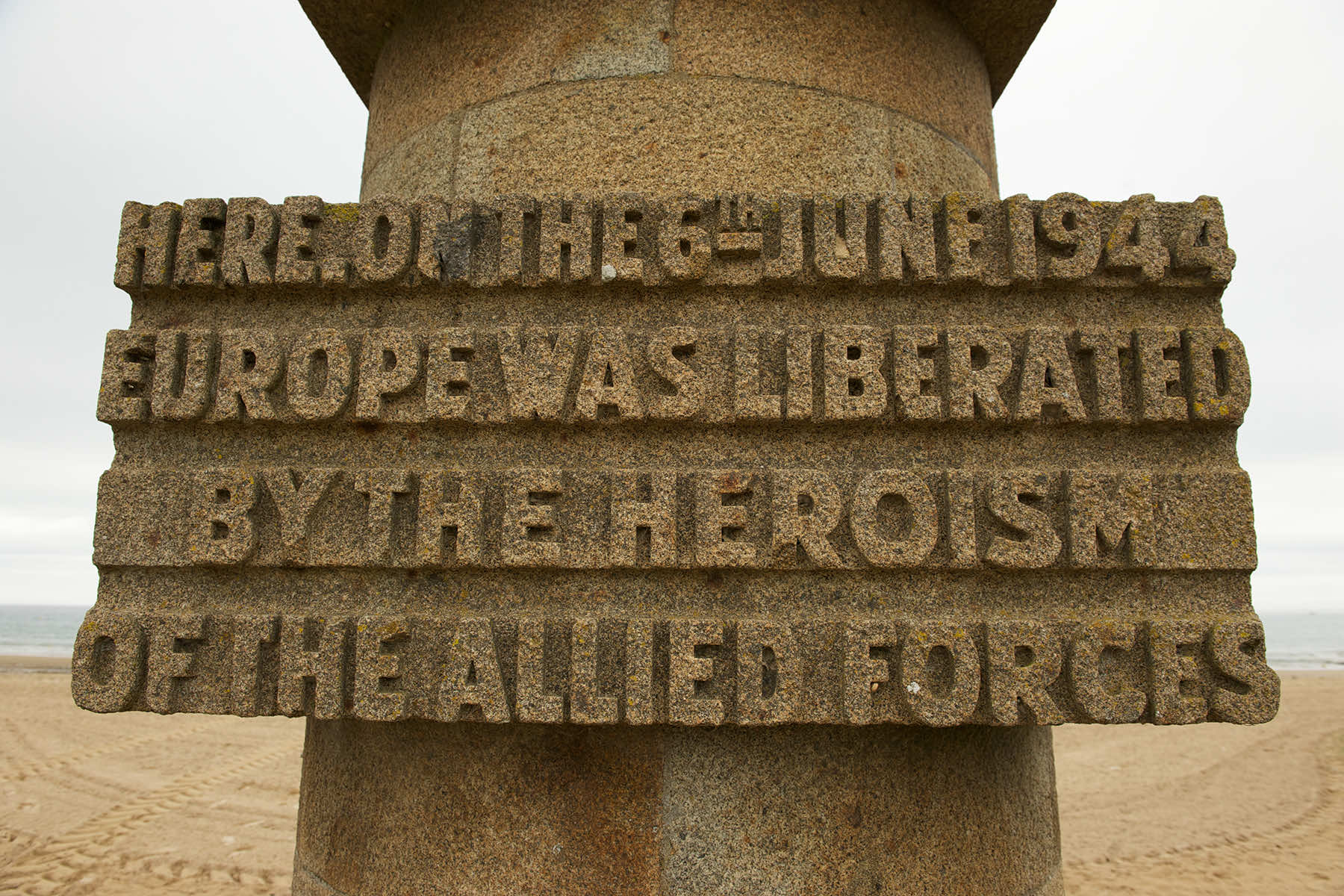

As Europe commemorates the 80th anniversary of D-Day on June 6, visitors have traveled in large numbers to pay their respects at the Normandy beach landing sites.

The event in 2024 takes place in a very different world than the 75th anniversary five years before. Donald Trump is facing numerous criminal charges from rigging the 2016 election to become president to the January 6, 2021 coup and insurrection to stay in office after he lost the 2020 election to President Joe Biden.

Trump’s benefactor, the Russian dictator Vladimir Putin, launched an unprovoked and brutal full-scale invasion of the sovereign country of Ukraine – plunging Europe into the biggest land battle since World War II.

Estimates predict that just under two million “remembrance tourists” will visit the beaches at Normandy to mark the 80th anniversary this year, slightly less than the 2019 total.

It is easy to understand why so many people want to travel to see the major sites of what is, after all, one of the defining moments of World War II in western Europe, especially for any veterans or for the families of those who risked and sacrificed their lives.

But there are also those who find the idea of visiting places linked with such death and destruction to be a little macabre. There have been reports that Chinese authorities are keeping tight security around Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on the 35th anniversary of the crushing of student protests in 1989 in which hundreds were killed.

Holidays in Hell

“Dark tourism” is a growing market. Whether the whole point of a holiday is to visit all the battlefields of Normandy, or whether it is a side trip on a visit to Poland to take in Auschwitz – and people have plenty of good reasons to take a detour to this appalling death camp, not least as an educational experience – many people, at least once in their lives, decide to skip the beach resort and opt instead to visit dark tourism sites.

Dark tourism, also known as black-spot tourism, morbid tourism, or thanatourism – after the Greek word “thanatos” meaning death – was identified in the 1990s. It is defined as “an attraction for places associated with death.”

Researchers have found the trend difficult to accurately pinpoint as tourists may not necessarily realise they are visiting a site identified as a “dark destination”. But more than 2.1 million people visited the concentration camp at Auschwitz in 2018 while the 9/11 memorial in New York attracted more than 6.8 million visits in 2017.

The notorious Alcatraz prison in the US attracts an estimated 1.4 million visitors each year. And, interestingly, given the widespread perception of the health risks involved, the site of the 1986 nuclear disaster at Chernobyl in Ukraine is also becoming a popular destination for the curious.

Following the huge success of the recent television drama series about the disaster, you wouldn’t bet against visitor numbers to Chernobyl increasing from the estimated 50,000 people who visited in 2017. The same trend is identifiable at the site of the 2011 nuclear disaster at Fukushima in Japan, which received an estimated 17,000 visitors in 2018.

Morbid fascination?

The reasons that people give for visiting these dark tourism sites are many and varied. They can include wanting to understand one’s family history and paying respect to relatives. There is also a desire for empathy or identification with the victims of atrocity or wanting to see a significant site for the purpose of education and understanding. Of course, sometimes, there is an element of voyeuristic attraction to horror.

Sadly not everyone approaches these sites with the respect they deserve. We live in the era of the “selfie” and, despite being obviously inappropriate, there have been reports of hordes of tourists queuing to take photos of themselves at the 9/11 memorial. This, in turn, has led to calls for “selfie sticks” to be banned from Ground Zero. Similarly, visitors to Auschwitz have been asked to stop posing for photos while balancing on its infamous railway tracks.

Whatever their reasons for visiting sites associated with suffering, death, and grief, many people find their visits cathartic and fulfilling. There is no doubt that among the many people coming to Portsmouth – or travelling to the battlefields of France – for the 80th anniversary of D-Day there will be many for whom it is the first chance to pay tribute to a parent or grandparent who sacrificed their lives for a greater good.

So for anyone else who might be drawn to these places out of a sense of curiosity, or simply because it is a “bucket list” destination, remember that in the eyes of many people such places are considered to be treading on sacred ground. So it is recommended to walk softly.

Liz Sharples and MI Staff

Alessandro Colle, Mila Croft, Bill Perry, Olrat, Adolf Martinez Soler, Rudolf Prchlik, and Everett Collection (via Shutterstock)

Originally published on The Conversation under a Creative Commons license as Dark holiday: D-Day and the growth of ‘grief tourism’ with edits by MI Staff to update for 2024.

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.