By Say Burgin, Assistant Professor of History, Dickinson College

Since the murder of George Floyd in 2020, some White people have been wondering how they can work with Black people to fight racial inequality.

As a history professor who studies social movements, I know this is not a new question. In the 1960s, civil rights activists deliberated how to channel White support for racial equality.

These conversations took place in cities across the country. In Detroit, White residents responded with particular enthusiasm. There, as I documented in my 2024 book, Organizing Your Own: The White Fight for Black Power in Detroit, their joint deliberations led to a strategic innovation in organizing that became foundational to Black Power.

A NEW STRATEGY

For some civil rights activists, like the late Georgia U.S. Rep. John Lewis, interracial organizing seemed like the best tactic.

The organization that he began leading in 1963, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, had always been Black-led. But it also included White activists who did community organizing or office tasks alongside Black workers. For Lewis, when White and Black activists worked together, they represented the kind of integrated society they were fighting for.

The Civil Rights Movement, Lewis said in 1988, offered “the only real and true integration that existed in American society.”

Yet, interracial organizing had obvious limitations. White activists often assumed they knew best, and that stymied the development of local Black leadership. Moreover, as historians including myself have documented, law enforcement and some local White communities responded violently as they watched White and Black activists organizing side by side.

The story of Detroit’s chapter of the Northern Student Movement illustrates the problems associated with interracial organizing.

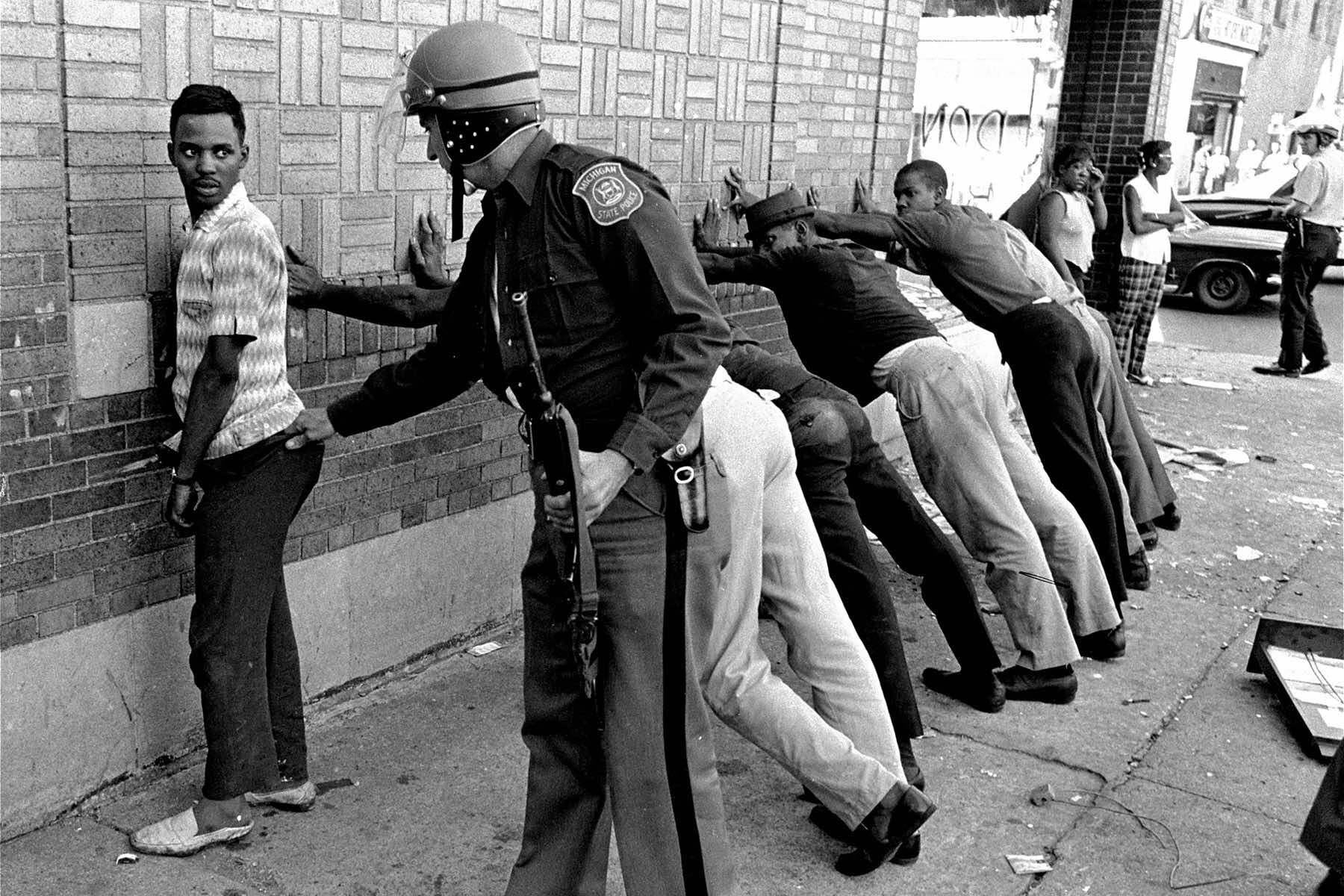

The group was founded in New York in the early 1960s by an interracial mix of college students who wanted to challenge Northern Jim Crow. This system of racial oppression was characterized by overpolicing of Black neighborhoods, unequal treatment in the courts, segregated and underfunded schools for Black children, and employment discrimination.

In the spring of 1964, the organization realized that White women faced difficulties when they went door-to-door talking to community members in Black urban areas as part of the group’s organizing efforts. These incidents suggested that interracial organizing was hindered by both gender relations and White people’s unfamiliarity with Black communities.

This discovery prompted the Northern Student Movement to enact a division of labor segregated by race and gender. In all the movement’s projects, White women were directed away from organizing in Black neighborhoods.

Then, in 1965, the group’s Detroit chapter became embroiled in a controversial campaign that prompted it to racially divide movement work even further.

In March, a White shop owner on Detroit’s west side killed a 20-year-old Black man named John Christian. Christian tried to intervene when the shop owner accused a child of stealing a 12-cent cake, and the shopkeeper shot Christian.

The Wayne County prosecutor refused to bring charges for the killing. In response, Detroit’s Black community began boycotting the shop and organized a campaign to have the shopkeeper arrested.

The Northern Student Movement quickly joined the effort. But, some White members in Detroit weren’t sure of the boycott’s moral righteousness. They were used to backing boycotts of racist Jim Crow laws in the South – not in the North. Other White members of the group took on the task of convincing their White peers that the Detroit boycott was the right move. These members knew they needed to enlarge White support for the campaign to succeed.

Meanwhile, the boycotters were being arrested, spuriously charged with conspiracy and given high bails. The government’s weaponization of the legal system convinced many activists that if a critical mass of White people vocally supported Black liberation, it could better protect Black activists.

A strategy began to take shape in the Northern Student Movement. Black activists would toil away at the main movement work of community organizing in Black areas and developing local leadership. White activists would organize in White areas and institutions, showing White people the pressing problems of racial inequalities and building support for civil rights.

I call this innovation racially parallel organizing. As local Black organizer Dorothy Dewberry said, it asked White people to “begin to work in their own communities.”

RACIALLY PARALLEL ORGANIZING IN PRACTICE

The Northern Student Movement became the first group to make racially parallel organizing its official strategy. In 1965, it asked its White members in Detroit to form a parallel group, which became known as People Against Racism.

People Against Racism worked with Black-led groups across Detroit to fight such Northern Jim Crow problems as unequal education and police brutality.

For example, when Black high school students led a walkout in 1966 to demand the ouster of a school police officer and a more rigorous education, People Against Racism helped run an alternative “freedom school” for the boycotting students to attend while they fought to improve their public school.

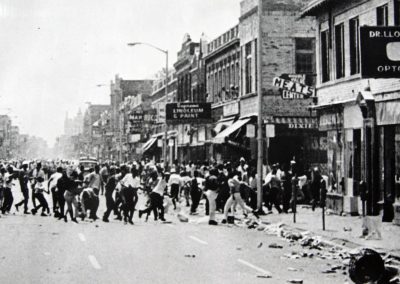

People Against Racism boosted its ranks after Detroit in 1967 experienced one of the deadliest racial uprisings of the decade. Suddenly, more White people wanted to understand why Black people were rebelling — and how they could address their problems. The group’s leadership ushered them into racially parallel organizing.

For instance, People Against Racism helped to reorient a Christian group called Detroit Industrial Mission, which had consulted with industry managers in Detroit industries for years, to address racial inequalities in employment. The group took cues from People Against Racism as it developed “new White consciousness” and “new black consciousness” trainings to confront the nearly all-White world of industrial management in Detroit.

The group helped numerous companies, including Detroit Edison and parts manufacturer Borg & Beck, establish affirmative action programs to increase Black hiring.

A PATH FOR WHITE SUPPORTERS OF BLACK FREEDOM

Then, in 1970, members of the Detroit Industrial Mission and People Against Racism, along with other groups, teamed up to found a group that represented the height of racially parallel organizing in Detroit.

The Motor City Labor League was the White parallel to Detroit’s most important Black Power group, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, a Marxist-inspired organization that sought to wage a race-conscious class struggle in Detroit industries. The Motor City Labor League, in turn, was tasked with mobilizing White communities near the League of Revolutionary Black Workers’ main base in Detroit’s Chrysler plants.

The group splintered due to infighting in 1972 but had some success in its short lifespan. For instance, the league helped White residents near one plant to see how Chrysler’s pollution harmed both them and the plant’s mostly Black workforce.

More importantly, racially parallel organizing set a clear path for White supporters of Black freedom. My research shows that in Detroit, its impacts were felt in boardrooms, factory floors, Sunday sermons, suburban neighborhoods, and public-school curricula.

The genius of the strategy was that it could be practiced anywhere that White people lived, worked and worshipped. It was replicated and practiced all over the country.

More than 50 years later, it can still speak to anti-racist activists as the struggle for racial equality continues.

Associated Press File Photo

Originally published on The Conversation under a Creative Commons license as White and Black activists worked strategically in parallel in Detroit 50 years ago, fighting for civil rights

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.