While pundits and scholars continue to debate the extent to which Donald Trump’s time in office has eroded American democracy, what is clear is that the former president’s political rhetoric breached the boundaries of acceptable racial discourse in the United States.

Trump assailed Mexicans as criminals, called for a ban on Muslims, said African nations were “sh*thole countries,” and referred to white supremacists in Charlottesville as “very fine people.” In his final act as president, he showed no remorse for the deadly violence he instigated during the January 6, 2021 Capitol riots with his lies about a stolen election. In so doing, Trump mainstreamed white supremacy and a new, more aggressive racial discourse which encouraged his supporters to resist “cancel culture,” the “woke media,” and any semblance of liberal or progressive ideas around identity and race – including using violent resistance to “take back our country.”

Take, for instance, Trump’s executive order banning federal contractors from conducting racial sensitivity training which claimed that such training indoctrinated government workers with “divisive and harmful sex and race-based ideologies.” From banning diversity training to denouncing the New York Times and its 1619 Project on slavery in the U.S. and Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, which offers an analysis of U.S. history told from the perspective of the oppressed, Trump, his allies and supporters engaged in a full-scale culture war just as a “racial reckoning” was taking place at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The massive protests in the summer of 2020, which came about in response to the violent death of a Black man, George Floyd, at the hands of law enforcement, sparked a backlash from the political right which took advantage of white American fears – real or imagined – of becoming a majority-minority.

Fearing a loss of power and influence should the government capitulate to the demands of a rapidly growing non-white majority, conservative activists like Christopher Rufo declared “a one-man war against critical race theory in the federal government.” Once Rufo was on Trump’s radar through his appearance on Fox News in late summer 2020, the campaign against critical race theory (CRT) gained such momentum that many school boards across the U.S. have recently voted to ban books focused on cultural diversity, gender/sexual and racial identity. The American Library Association has reported more than 300 book challenges since last autumn with that number increasing rapidly as the anti-CRT movement continues to grow.

It is important, however, that we do not overlook the fact that there is nothing new about Trump’s culture war in the larger context of American political and social discourse. In fact, it is safe to say that what Trump and various conservative activists, politicians and pundits have offered is a repackaging of conservatives’ long-standing racial backlash strategy against groups pushing for the U.S. to live up to its promise of equal justice and liberty for all.

To understand the strategy of conservative racial backlash, we need to look back further to understand how race factors prominently in American political culture, focusing particularly on how philanthropy was used by the American conservative movement to shape its views on race and disseminate these views to an often unsuspecting public.

Race and seeds of conservative discontent

The seeds of conservative discontent with American political and social institutions can be traced back to the 1940s when the three groups which unified under the term “conservative” – libertarians, traditionalists and anti-communists – banded together to undermine the influence of then-president Franklin D Roosevelt (FDR) and his brand of liberalism.

Prior to the election of FDR, liberalism was associated with laissez-faire economics and limited government in the US. What Roosevelt offered in contrast was a “New Deal” liberalism that promoted economic liberalism with social democratic safeguards in response to the Great Depression. For Roosevelt, “the new deal for the American people” meant there was a “duty and responsibility of government toward economic life.”

Overwhelmed by the Great Depression, bankers and businesspeople initially urged Roosevelt to take extraordinary steps to get the economy back on the road to recovery.

However, these same business leaders were appalled by the utilitarian overtones inherent in the programs which Roosevelt proposed to reboot the American economy. First, many of these business leaders took great exception to the president’s reliance on a group of academics to serve as his key political advisers. Known as the “Brain Trust,” this diverse group of scholars including the president’s legal counsel Samuel Rosenman, professors Raymond Moley, Rexford Tugwell and Adolf Berle of Columbia University, lawyer Basil O’Connor and Felix Frankfurter of Harvard Law School, offered Roosevelt a variety of approaches for handling the economy during the Great Depression.

Opponents of FDR, who were often members of the Republican Party, used the term “brain truster” disparagingly, believing this group of academics was steering the nation towards socialism. Secondly, the passage of the Wagner Act, which enabled workers to organize unions and call labour strikes, was bitterly contested by the Republican Party which viewed this legislation as a threat to its freedom. Some business groups like the American Liberty League encouraged its wealthy business members to file injunctions in court and refuse to abide by the legislation that was signed into law by Roosevelt in 1935.

Furthering the Republican discontent with Roosevelt’s New Deal policies were the overtures made to African Americans, particularly with the establishment of The Federal Council of Negro Affairs (also known as The Black Cabinet). This was a group of African American public policy advisers to President Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor from 1933 to 1945. Although the Black Cabinet was not an official organization, by the mid-1930s, more than 40 African Americans were working in various parts of the federal government and with New Deal agencies across the country. Many white business leaders and wealthy elites were alarmed by Roosevelt’s allowances to African Americans, believing such actions would eventually spell their doom.

Absent from a great deal of the scholarship on the rise of the modern conservative movement in the U.S. is an analysis of how race and racism figured prominently in propelling this new political philosophy forward. African Americans’ demand for the expansion of civil rights fueled the eventual creation of a “conservative labyrinth” of philanthropy foundations, think tanks and political lobbyist groups that would disseminate ideas to challenge liberalism and act as a bulwark against the “browning” of America.

The limits of racial liberalism

Roosevelt’s small concessions to African Americans did usher in a very brief period of racial liberalism, which emboldened African Americans to press the federal government for expanded civil rights during the 1940s. Racial liberalism emerged as a political philosophy during World War II based on two central tenets in which (1) government should lend a hand in ending racial discrimination and (2) there should be an emphasis on “equal opportunity legislation” focused on dismantling racial segregation.

One of the most important developments to come out of this period of racial liberalism was the “Double V” campaign, which was a slogan used to rally African Americans to fight for victory at home and abroad during World War II. The campaign had only limited success highlighting the fact that the notion of racial liberalism never had widespread popular support.

The reason for this lack of support for racial liberalism can best be explained with the theory of interest convergence as espoused by Derrick Bell, the late legal scholar and co-founder of the Critical Race Theory movement. According to Bell, unless white Americans see a benefit for themselves, they will never promote and support civil rights legislation or economic policies which exclusively benefit African Americans.

Even when presented with opportunities to sign an anti-lynching bill or desegregate the military, for example, Roosevelt capitulated to political expediency and his political opponents like FBI director J Edgar Hoover. Historians like Jill Watts question whether Roosevelt was a genuine friend to African Americans, based in part on his administration’s lack of oversight of New Deal programmes, particularly in the American South where African Americans experienced extreme racism when trying to access New Deal benefits, and, for his failure to desegregate the armed forces.

However, when Roosevelt appointed William Hastie as the first African American federal judge or two million African Americans were hired for projects undertaken by New Deal-sponsored programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration, Roosevelt became the first American president since Abraham Lincoln to take up causes of particular importance to African Americans. The access that African Americans had to the president and his wife was viewed in apocalyptic terms by conservatives who feared the policies aimed at helping to lift African Americans out of poverty would usher in a period of pronounced interest divergence for their business and political interests.

The principle of interest divergence, which functions as the inverse of interest convergence, holds that Black people’s demands for racial equity will not be accommodated when those interests diverge from the interests of white people. Conservatives firmly believed that any government intervention designed to increase employment opportunities or extend civil rights protections to African Americans would hurt them economically and would turn the U.S. into a liberal welfare state.

The conservative unification process

To halt the expansion of the liberal welfare state, three disparate groups – libertarians, who believed in less government control of the economy; traditionalists, who promoted strict religious adherence, patriotism and separation and segregation of the races; and anti-communists, who were particularly concerned with the spread of communism in the U.S. and around the world – came together following Roosevelt’s death in 1945 to begin the process of unifying and building an ideological infrastructure that could take on liberalism in the marketplace of ideas.

Libertarians, traditionalists and anti-communists’ ultimate goal in unifying under a singular political philosophy was to gain political power that would ensure that the interests of American big business would always be protected.

The events of 1945, including World War II and the power vacuum left by Roosevelt’s death in office, provided these groups with the opportunity to offer Americans an alternative political and social philosophy around which to rally. Conservatism was not necessarily new or unique to the U.S. but what distinguished this modern formulation was that it would become better conceptualized and disseminated and it would use many of the same types of organizing techniques that helped Roosevelt rise to political power, including establishing philanthropic organizations, as well as making use of the media and grooming charismatic, dynamic leaders.

From 1945 to 1955, conservatives reformulated the working definition of their belief system to overcome any ideological differences ensuring that they were creating an assertive rather than reactionary ideology. The anti-communism strand was emphasized as it bridged the gap between all factions, since anti-communism served to not only protect the U.S. and the West from encroachment but also worked to promote conservative values at home. The primary method used to help unify the three factions of conservative thought was through the creation of a conservative scholarly journal that would help to disseminate conservative ideas to a broad cross-section of the academic community.

Conservative intellectuals such as William F Buckley Jr believed that in order to have legitimacy and staying power among the American public, modern American conservatism had to emerge from academia as Roosevelt’s New Deal policies were originally developed by the Brain Trust. Buckley realized that liberalism as an intellectual movement was still alive (even with the death of Roosevelt) and that conservatism still lacked sufficient focus to challenge liberalism.

It was the National Review, a multi-faceted conservative journal that was the brainchild of Buckley, that offered the burgeoning conservative movement its first real opportunity to have ideological cohesion. Likewise, National Review’s inclusion of two opinion columns – “From the Academy” and “The Ivory Tower” – critiqued the liberal intellectual class in America’s colleges and universities by exposing what conservatives believed to be the excesses of university faculty and administrators. Thus, with the publication of the National Review, conservatism would become a legitimate political and social philosophical alternative to liberalism which began losing some momentum – at least within the academy – during the turbulent 1960s, brought on by widespread student protests, public marches and demonstrations and violent clashes between African Americans and the police.

Shortly after the National Review burst onto the scene and the ideological debates generated by the journal became more widespread, conservatives began contemplating how they would extend their influence into the political realm of American society.

Realizing that the only way for their political ideology to have relevance in Washington was to work through the two-party political system, conservatives were prepared to use the Republican Party as the vehicle to consolidate their power and bring conservatism to the American public. But how could such a young movement, seen by many in the political establishment as an aberration, use the Republican Party in such a way that by 1964, less than 20 years since its founding, it was poised to take control of the White House?

Interestingly enough, conservatives got a boost from former Brain Trust member, Raymond Moley, who left the team of advisers to the president in 1936 because of his strong opposition to Roosevelt’s concessions to African Americans and pro-union labour groups. In his 1952 publication, How to Keep Our Liberty, Moley explained his opposition to these concessions describing how demographic shifts in the US, as evidenced by 1920 census data, would favor an urban majority which would mean that Roosevelt would have to continue making concessions to African Americans and northern ethnic whites (mostly Irish and Italian) who made up a large part of the U.S. labour movement. Instead, Moley walked away from the Brain Trust with the belief that the Democratic Party was driving the country into the ground and he feared that the free-market system would be replaced by socialism.

Nearly 20 years after leaving the Brain Trust, Moley refused to build alliances with the liberal or moderate factions within the Republican Party but he encouraged his fellow conservatives to support Dwight D Eisenhower publicly while working behind the scenes with academics, politicians and wealthy business owners to develop plans for the conservative takeover of the Republican Party.

Race, repression and the hysteria of anti-communism

Aiding Moley and other conservatives in their quest to not only take control of the Republican Party but also win over the American public in the battle of ideas against liberalism was the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The vast majority of Americans paid little attention to ideological debates over communism and anti-communism which presented conservatives with the opportunity to shape the public’s ideas about communism to suit their needs.

At the end of World War II, Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin initiated a Second Red Scare in 1950 when he claimed to have a list of alleged members of the Communist Party of the USA who worked inside the U.S. State Department. McCarthy’s accusation created a media frenzy which in turn led to a heightened period of political repression and a campaign of fear of a communist overthrow of the U.S. government. Despite McCarthy lacking evidence to prove such allegations, the primary targets of this repression were government employees, academics, labour-union activists and those in the entertainment industry.

While most white middle-class Americans moved to the suburbs and became preoccupied with the baby boom, consumption and a renewed embrace of domesticity, African Americans saw the end of racial liberalism and a return to the strict racial status quo during the McCarthy era which lasted until the mid-1950s.

The racial norms of segregation, disenfranchisement, and subordination that African Americans faced before and during the war only seemed to grow stronger when the U.S. entered into the Cold War with the Soviet Union. Those who dared to speak out about the living and working conditions facing African Americans in the urban ghettos and racially segregated parts of the American South found themselves with little to no support from the federal government. Many prominent African American activists such as actor/singer Paul Robeson and civil rights activists W E B DuBois and William Patterson were accused of having ties to communism which placed them in the political crosshairs of the FBI.

The FBI had begun compiling surveillance files on these three men as early as 1942. In 1947, the Civil Rights Congress and the Council on African Affairs, organizations to which Robeson, DuBois and Patterson were all intimately involved, were placed on the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations.

Being labelled communist during this period had severe negative economic and political consequences for these activists including having their passports revoked which affected Robeson’s ability to travel for his work as an actor. Robeson was also called before the House Un-American Activities Committee to sign an affidavit affirming he was a not communist. DuBois was charged with acting as a foreign agent because of his work calling for a ban on all nuclear weapons in 1951. The government’s treatment of African American civil rights and social justice activists was nothing more than an attempt to silence African Americans and keep them in their place.

A few years later, during the Civil Rights Movement, white segregationists such as former Alabama Governor George Wallace and other conservatives began utilising specific rhetoric about the evils of communism which helped bring white Southern Democrats to the Republican Party. Conservatives reinforced the principle of interest divergence, insisting that any civil rights legislation proposed by liberal Democrats meant a loss of freedom for white Americans. In his 1963 inaugural speech as governor, Wallace argued that the Civil Rights Movement would be worse than what the Nazis did to Jews “so the international racism of the liberals seek to persecute the international white minority to the whim of the international colored majority.”

Despite the realities of racial violence and political disenfranchisement of African Americans, conservatives’ anti-communist rhetoric and the crackdown on civil rights activists by the FBI assured members of the economic and political elite that the American racial status quo would not be upended. To further prevent a resurgence of racial liberalism, individual American big business leaders began using their vast financial resources to support the candidacy of conservative politicians such as Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan to wrestle control of the Republican Party away from its more liberal and moderate factions. These liberal and moderate factions were accused of playing politics with the Democrats and acquiescing to the demands of racial minority groups.

Raymond Moley, for example, was especially harsh in his criticism of Republican President Eisenhower who supported the landmark 1954 Brown versus Board of Education decision which helped to desegregate schools. The National Review ran articles claiming the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren and Associate Justice William Brennan, both Eisenhower appointees, had allowed liberalism to take root in the judiciary due to a number of rulings by the Warren Court which led to the end of McCarthyism. Additionally, both justices voted in favor of the African American plaintiffs in the Brown versus Board of Education decision.

The mounting tensions between the conservatives and the other factions of the Republican Party became very apparent as the 1960 presidential election neared. Conservatives believed that Nixon, the Republican frontrunner and Eisenhower’s vice president, could not be trusted because of his moderate stance on school desegregation. Believing that Nixon would not deliver on Eisenhower’s promise to undo various New Deal programs, Barry Goldwater, a conservative Arizona senator challenged the Republican Party to “grow up” and work to put the party back together using a local, grassroots approach rather than engage in what Goldwater labelled as “establishment treachery.”

Goldwater was a political outsider to the Republican establishment because of his views on limited government, the free market system, discontent with the Civil Rights Movement, and his outspoken support for a strong national defense which he laid bare in his 1960 publication, Conscience of a Conservative. Goldwater’s conservative beliefs and frankness were characteristics that endeared him to conservative peers like William Rusher, publisher of the National Review and John Ashbrook, a congressman from Ohio, who organized a series of secret meetings with Republican operatives and conservative business leaders to plan the Republican Party strategy for winning the White House in 1964 with Goldwater as their standard-bearer.

Philanthropy and Goldwater conservatism

To break the liberal and moderate hold on the Republican Party, Goldwater needed more than a strong message; he needed money. Conservatives initially had to depend on “rank and file” money from ordinary Republican Party supporters, according to Mary Brennan, author of Turning Right in the Sixties: The Conservative Capture of the GOP. Instead, Goldwater’s campaign received substantial financial support from members of the wealthy business elite at the time, including Fred Koch, founder of the oil refinery that would become Koch Industries, the second largest privately held company in the US; Richard Mellon Scaife, heir to the Mellon banking, oil and aluminium fortune and founder of the Carthage Foundation, a conservative anti-communist political club focused on national security issues; and Harry Lynde Bradley, co-founder of the Allen-Bradley Company and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, a conservative philanthropic foundation with over $800m in assets.

These wealthy donors were staunchly conservative in their political outlook with Koch and Bradley having been members of the ultraconservative group, the John Birch Society, best known for spreading conspiracy theories about communist plots to overthrow the United States.

Donations from these billionaires were used by the Goldwater draft team to help organize at the precinct, district and state level to build delegate strength for the 1964 Republican National Convention as opposed to trying to sway national party officials to the conservative cause. With the aid of conservative donors, Goldwater secured the party nomination and the conservative grassroots operation was solidly in place for years to come.

Despite losing the election, Goldwater’s campaign breathed new life into the Republican Party. He helped the party gain support in the South which had been traditionally Democratic but was largely opposed to integrationist policies such as the Brown versus Board of Education decision. Goldwater also popularized the states’ rights position on racial integration arguing that the federal government had no business interfering in what was a state’s right to enforce integration orders or not.

Goldwater broke with liberal and moderate members of the Republican Party when he voted against the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, believing that African Americans should adopt a policy of gradualism and wait until southern whites were ready to embrace them as full citizens. Even when members of the John Birch Society, regarded in many Republican circles as a fringe group, threw their support behind Goldwater, he remained adamant that he would suffer the kooks and lose the election if it meant that conservatives could win the party.

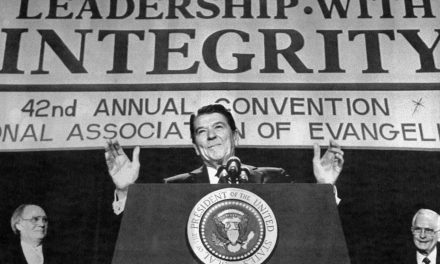

It was the conservative capture of the Republican Party through the campaign of Goldwater that paved the way for his heir apparent, Ronald Reagan, to become governor of California and later become the first modern American conservative president of the US.

Race and Reagan’s ascent in California

Liberals failed to anticipate how the volatile issue of race would affect white American voters, who, by and large, clung to a strong belief in tradition and order. Liberals readily assumed that their traditional base of support – labour, African Americans and white ethnic communities would always remain firm. By the 1960s, however, liberals were no longer championing “bread and butter” issues such as wages and taxes which affect everyone.

Lower-middle class white ethnic voters tended to be deeply religious and favored traditional family values so when Reagan made the charge that urban rioters, Vietnam War protesters and civil rights activists were the greatest threats to freedom and civility, these white conservative Democrats, as they were labelled by Reagan’s campaign staff, threw their support behind the Republican gubernatorial candidate and never looked back.

Reagan took advantage of the perception – real or imagined – that liberal social programs such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 encouraged African Americans to make even greater demands and would result in arson and murder as the first act of civil disobedience. Buoyed by a 1966 national Harris poll, which found that the number of white Americans who believed African Americans tried to “move too fast” in their demand for civil rights grew from 34 percent in 1964 to 85 percent just two years later; Reagan used this polling data to call for a crackdown on anti-war protesters and civil rights activists.

In one of his first acts as governor, Reagan signed the Mulford Act which repealed a law that allowed the carrying of loaded firearms in public. This bill was drafted for the primary purpose of disarming the Black Panther Party which had lawfully carried loaded guns to patrol neighborhoods in Oakland to prevent police abuse of African Americans.

Reagan cultivated an image of stability and order with his nonsense crackdown on Black radicals. He was lauded by fellow conservatives for his decision to call in the U.S. National Guard to put down the five-month student protest for the establishment of a Black Studies program at San Francisco State College. He used the “radical” politics of the Black Panther Party, Students for a Democratic Society, and even calls for the desegregation of public schools in California from moderate civil rights organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to propel himself into national prominence.

By the end of his second term as governor, the conservative political machine which helped Goldwater run for the presidency in 1964 was once again set in motion to help Reagan go all the way to the White House with one important difference: Reagan would have access to an even greater largesse of conservative philanthropic support that could provide much-needed capital to not only win the Republican nomination but to make conservatism the dominant political force in the U.S. for generations.

The Powell Manifesto and the rise of movement conservatism

In 1971, two months prior to Richard Nixon nominating him to the U.S. Supreme Court, Lewis F Powell Jr sent a private memo, entitled Attack on the Free Enterprise System, to various members of the U.S. business community in which he outlined the assault on big business and what should be done about it. This memo, also known as “The Powell Manifesto,” specifically focused on how big business was attacked from within academe. Powell says, “Although origins, sources and causes are complex and interrelated, and obviously difficult to identify without careful qualification, there is reason to believe that the campus is the single most dynamic source. The social sciences faculties usually include members who are unsympathetic to the enterprise system.”

Powell suggested various ways in which members of the business community could halt the attack on the enterprise system by financing and sponsoring a “counter-establishment” starting with U.S. higher education. Eventually, Powell suggested, once conservatives’ influence over U.S. higher education was solidified, conservatives could press for control of the media, local and state court systems, and local, grassroots politics.

The aim of the conservative counter-establishment was to dissuade American politicians from enacting legislation that would increase regulation and taxation on American big business by turning American public opinion against liberalism.

Many of the same concerns that the American business community had with liberalism and the New Deal in the 1930s was echoed in the 1970s, except now, Powell laid out a detailed action plan for business leaders to combat liberalism. Likewise, while individual conservative donors supported the Goldwater campaign, what Powell called for was a much larger investment of money to cement the marriage between conservative academics and political leaders with U.S. big business. This philanthropic support led to a new form of political activity known as movement conservatism.

Movement conservatives promote the commercial interests of the corporate elite rather than the general interests of the American public by funneling millions of dollars into the creation of foundations and think-tanks that would develop policy analyses and research for politicians.

By the mid-1970s, movement conservatives began developing a vast network of foundations, think-tanks and academic policy organizations to remove all remaining vestiges of the liberal welfare state, particularly government-funded race and gender-based legislation such as affirmative action. This network included academic reform organizations such as the National Association of Scholars (NAS), think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute, and conservative family foundations including the John Olin Foundation, the Charles Koch Foundation, and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation. In fact, the initial seed money to establish the Heritage Foundation came from Joseph Coors, grandson of the brewery magnate Adolf Coors, being “stirred up” to support the conservative cause after receiving Powell’s memo. Soon, other wealthy conservatives like Richard Mellon Scaife and John M Olin were setting up their own family foundations to support a variety of conservative causes and politicians.

Launching the academic culture wars

With this new conservative philanthropic infrastructure in place by the mid-1980s, movement conservatives launched the academic culture wars in U.S. higher education in response to Powell’s call to first target academe. Similar to Powell’s critique of the social science faculty, William Bennett who served as the chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities and later as Regan’s secretary of education, published a report in 1984, entitled To Reclaim a Legacy: A Report on the Humanities in Higher Education, where he claims that the study of Western civilization has lost its central place in the humanities curriculum when he critiqued Stanford University’s decision to add more works from women and people of color in a Western civilization course required of all freshmen students. This report launched the culture wars.

During the culture wars, affirmative action programs and ethnic and gender studies departments were targeted because these programs called into question who should have access to educational and economic opportunities while simultaneously providing a critique of capitalism and traditional racial politics in the US.

The primary goal of the culture wars was to silence critiques of capitalism and the existing social order by charging that ethnic studies programs, affirmative action and other race-based initiatives relied on cultural relativism in their criticisms of capitalism and the racial status quo in the US. Members of the NAS used monies from conservative foundations to claim that liberalism eroded academic standards and denied conservative faculty and students their right to academic freedom in their quarterly journal, Academic Questions.

From 1988 through 2005, according to the Foundation Grants Index, the NAS received more than $10m in grants from different conservative philanthropies including the Olin, Bradley, Scaife, Coors and Smith Richardson foundations to support a wide range of programs. In turn, these grants were used to fund conservative student newspapers such as the Dartmouth Review, fund internships to train conservative student activists, establish endowed fellowships for conservative scholars, and finance conservative educational policy institutes such as the Madison Center for Educational Affairs (MCEA).

The National Center for Public Policy Research, using donations and grants from the Carthage, Castlerock, Scaife and Earhart foundations and ExxonMobil, also created an African American conservative speakers’ bureau called the Project 21 Black leadership network in 1992.

Several members of Project 21, including economist Thomas Sowell, author Shelby Steele and conservative businessman and University of California regent Ward Connerly, were particularly outspoken against ethnic and gender studies and affirmative action during the culture wars. Connerly even called for an end to cultural graduation celebrations because they “promoted the balkanization of the nation” following his successful campaign to pass Proposition 209 in California, which ended affirmative action in state hiring, contracting and state university admissions in 1996.

To fund this anti-affirmative action consulting work, Connerly created the American Civil Rights Institute (ACRI), a non-profit organization designed to educate the public about the problems with affirmative action. In its first year of operation, ACRI received more than $4m from donors like the Bradley, Olin, Scaife, Hickory and Randolph foundations.

This new type of philanthropy moved away from the traditional notion of philanthropy as charitable, altruistic and providing for the common good. Instead, this philanthropy openly discouraged discussions of race or gender in the classroom or the promotion of diversity in the workplace. Activists, political operators and scholars receiving monies from conservative groups often relied on racially tinged rhetoric to scare people into not supporting affirmative action, ethnic studies and cultural-based student programs in universities. They emphasized race-neutral “fairness,” meritocracy and individualism rather than support policies that would diversify educational institutions or the workplace. Conservative think-tanks and institutes, such as the Heritage Foundation and Hoover Institute at Stanford University, helped to legitimize conservatism as an intellectual force that could compete with liberalism for domination in education, media and politics.

While academia was the initial battleground for the culture wars, movement conservatives got a boost from media coverage of the political correctness (PC) debates during this period. Newspaper and journal articles about these debates exploded in popularity from 101 articles in 1988 to 3,989 in 1991. PC debates provided an irresistible opportunity for print media to attract readers with sensationalized headlines, graphics and stories that played on the deepest fears of middle-class white Americans. The general public was largely unaware that most of these books and editorials were funded by conservative foundations such as Dinesh D’Souza’s Illiberal Education which was funded by the Olin Foundation..

While the academic culture wars was presented to the public as a battle over ideas within American colleges and universities, movement conservatives initiated the culture wars as an economic protectionist policy to protect their financial interests using a racial capitalism approach where the discourse on race is used to make the actual intent of this philanthropy opaque. By focusing on the language of meritocracy and using political correctness as a pejorative term to mean that racial minority groups and women could silence white men, movement conservatives could play on white American racial fears of the browning of America, convincing the unsuspecting public that policies benefitting African Americans and other racial minority groups were inherently unfair to the white majority.

Movement conservatives were able to channel popular anger about falling wages and living standards away from Wall Street and focus it instead on the Black poor and non-white immigrants. Writer Michael Lind has even suggested that conservatives launched the culture wars as a method of diverting “the wrath of wage-earning populist voters from Wall Street and corporate America to other targets: the universities, the media, racial minorities, homosexuals, and immigrants.” Movement conservatives used the culture wars to fabricate issues and frighten voters – particularly low-income white voters – into voting for Republicans whose policies are devastating the very families they claim to represent.

We can see clearly how heightened fears of losing power in the wake of African American demands for civil rights led to the use of philanthropy to build a conservative “counter-establishment,” as writer Sidney Blumenthal refers to it, where race was a central organizing principle. This conservative counter-establishment had been working for decades, unbeknown to most of the American public, shaping and redefining the discourse around race in the US. By the time Trump announced his candidacy for the presidency, racial polarization and the conservative backlash strategy was already firmly entrenched.

Donna J. Nicol

Library of Congress

Originally published as Racism and the roots of conservative philanthropy in the US