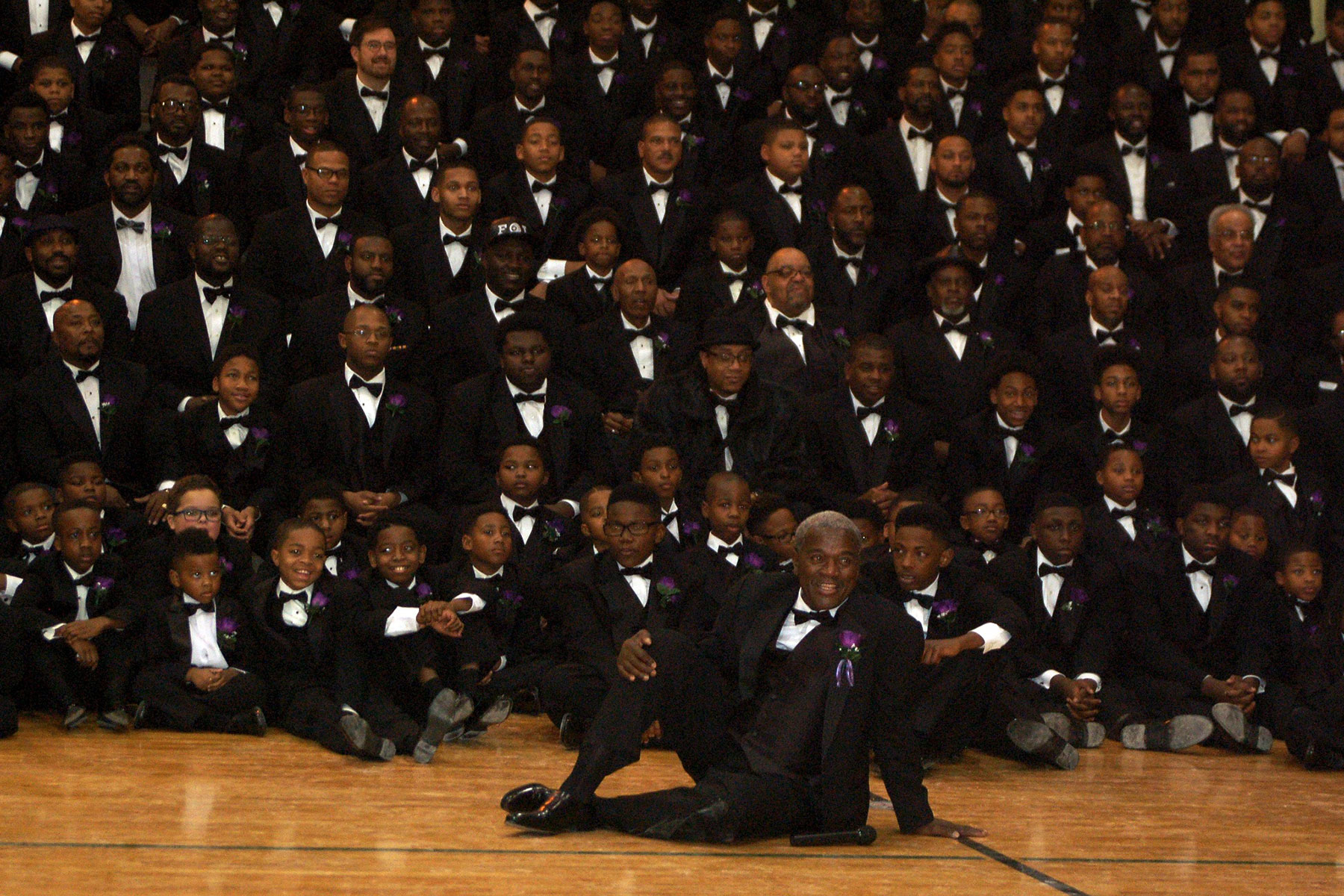

Andre Lee Ellis welcomed 500 men and boys in tuxedos at the start of the mentor program at Northcott Neighborhood House.

For several hours on Saturday morning, hundreds of African-American boys and men, ranging from preschoolers to 80-somethings, walked into Northcott Neighborhood House and crossed the lobby to a line of registration tables. After checking in, they proceeded to a makeshift cloakroom to collect pre-fitted rental tuxedos and down another hall to a changing room.

Emerging transformed from casually dressed to tuxedo-clad, they made their way, one by one and in small groups, into the gym, stopping to receive boutonnières, take selfies, pose for relatives and greet friends.

Numbering 500, the black boys and men braved a snowstorm to participate in the grassroots “We Got This” organization’s third annual tuxedo event, which pairs adult men with boys for mentoring and a formal dinner. Dubbed “From Boys in the Hood to Gentleman on the Town” in its first year, when 100 boys and men attended, organizers called this year’s event “500 Black Tuxedos.” Following drum performances and a rousing welcome by Andre Lee Ellis, founder of “We Got This,” and other community leaders, attendees boarded buses to the Hilton Milwaukee City Center for a formal dinner in the Crystal Ballroom.

Ellis said the event arose out of questions neighborhood boys asked on seeing him and his wife dressed up for an evening out. “500 Black Tuxedos” shows young, black boys from the central city a world beyond “the ‘hood.” It gives them an opportunity to see themselves in the larger world, experience wearing formal dress and dining in a formal setting, according to Ellis. It also connects them with a community of black men who act as father figures and mentors. In addition to giving the young men confidence, Ellis said the event also seeks to remind men in the community of their responsibility to guide its boys.

Adult participants agreed that young black boys in Milwaukee need mentors and said they were excited to be part of the event.

Don Bond, 19, participated last year as one of the young contingent. He was matched with mentor David Muhammad, violence prevention manager at the City of Milwaukee Health Department. A sophomore at Wisconsin Lutheran College, Bond liked last year’s event so much that he came back as an adult mentor to his younger brother Brandon Bond, 15.

Mentoring is important, Bond said, “because if you don’t steer young black men in the right direction, they will fall for anything.” They are racially profiled, so if they fit the profile, they’re just going to end up as another statistic, in jail or unemployed, Bond added.

“Focus on school and get good grades. Use your brain and stay out of trouble, … do what you’re supposed to do,” was his advice to his younger brother.

Bond said he has benefitted from his relationship with Muhammad, who he stays connected with through Facebook. “I shared my goals with him and he gave me his wisdom (about) how I can accomplish those goals,” he said.

Mentor Trevis Hardman, 24, grew up across the street from Ellis near 9th and Ring streets. A protégée of Ellis’ since Ellis moved to the neighborhood several years ago, Hardman recently moved to the Concordia neighborhood. He has built his own lawn care business, Dream Outlook Lawn Service, finding additional mentors among his clients. One of those is Robert Byrd, the former Marquette University basketball player, who owns a golf course in the city.

Hardman said his advice for the boy he mentored is to believe in and stay true to himself. “That’s pretty much what the ‘We Got This’ program is about, figuring out who you are as a young man, who you are in the community and who you are going to be in the workforce.”

Two military veterans volunteering for the first time this year both said they were fortunate to have strong mentors growing up. Electrician Willie Luckett, who lives on the Northwest Side, looked up to and emulated his older brother, who joined the Navy in 1978.

Luckett first thought he would participate by donating money but decided that contributing time and being there in person were at least as valuable. He added that by passing on the lessons that he was taught as he was growing up, he was contributing to the rebuilding of a cultural legacy that seems to have been lost.

Having traveled the world on four different Navy ships, Luckett said he would probably advise a boy to “go to the military; see the world, experience life. But if that boy wants to go to college, he should do that and be the best (he) can be,” Luckett added.

As director of peer support programs at Dryhooch, a nonprofit where veterans support veterans transitioning to civilian life, Otis Winstead understands the value of mentoring. He was attracted to the idea of mentoring young black men when he learned about 500 Black Tuxedos from his friend and associate, Northcott director MacArthur (“Mac”) Weddle.

Winstead explained that a principle of peer support is that the person being mentored should guide the relationship. It’s vital to discover what the boy is really interested in doing and “tap into his inner resources,” he said.

Contemplating the spectacle of 500 black boys and men in tuxedos filling the Northcott gym bleachers, Don Bond said, “I like how black people from all over the city come together, link arms and talk about how we’re going to make the community better.”

Andrea Waxman