Japanese cities, corporations, sports groups, and even tourist destinations have a long tradition of using iconic mascots as a way to promote brand identities. That habit has continued in the age of coronavirus, with the elevation of a 19th century “anti-plague demon” from Japanese folklore to help rally the public in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Known as Amabie (アマビエ), the humanoid fish yōkai – a class of supernatural spirits popularized in Japanese mythology, was first documented in 1846 and has been reborn as a mascot to drive off the coronavirus. A number of supernatural monsters and apparitions have captured the Japanese psyche for centuries, appearing in everything from ancient woodblock prints to modern-day manga. Yōkai often take on religious roles, like the shapeshifting kitsune fox spirit traditionally believed to be the messenger of the Shinto god Inari, which adorn Shinto shrines throughout Japan.

“Yōkai often play the role of helping people process unpleasant feelings or situations. They can sometimes be a kind of pressure valve for when things get tense,” said Hiroko Yoda, co-author of the book Yōkai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide. “What gives them weight is their long history. Yōkai, in various forms and names, have been part of Japanese culture for centuries. Today, yōkai are mainly a form of entertainment. They are commonly used as characters in video games, anime and comic books.”

Largely forgotten for generations, the story of Amabie began in the Edo Period (1603-1868) when a government official was sent to investigate a mysterious green light that emanated from the waters in Higo province, now present-day Kumamoto prefecture in southwestern Japan. When he arrived at the spot of the visual anomaly, a glowing-green creature with fishy scales, long hair, three fin-like legs, and a beak in place of a mouth emerged from the sea.

Amabie introduced itself to the official and predicted two things: a rich harvest would bless Japan for the next six years, and a pandemic would ravage the country. However, the mysterious entity instructed that in order to prevent the disease, people should draw an image of it and share with as many people as possible.

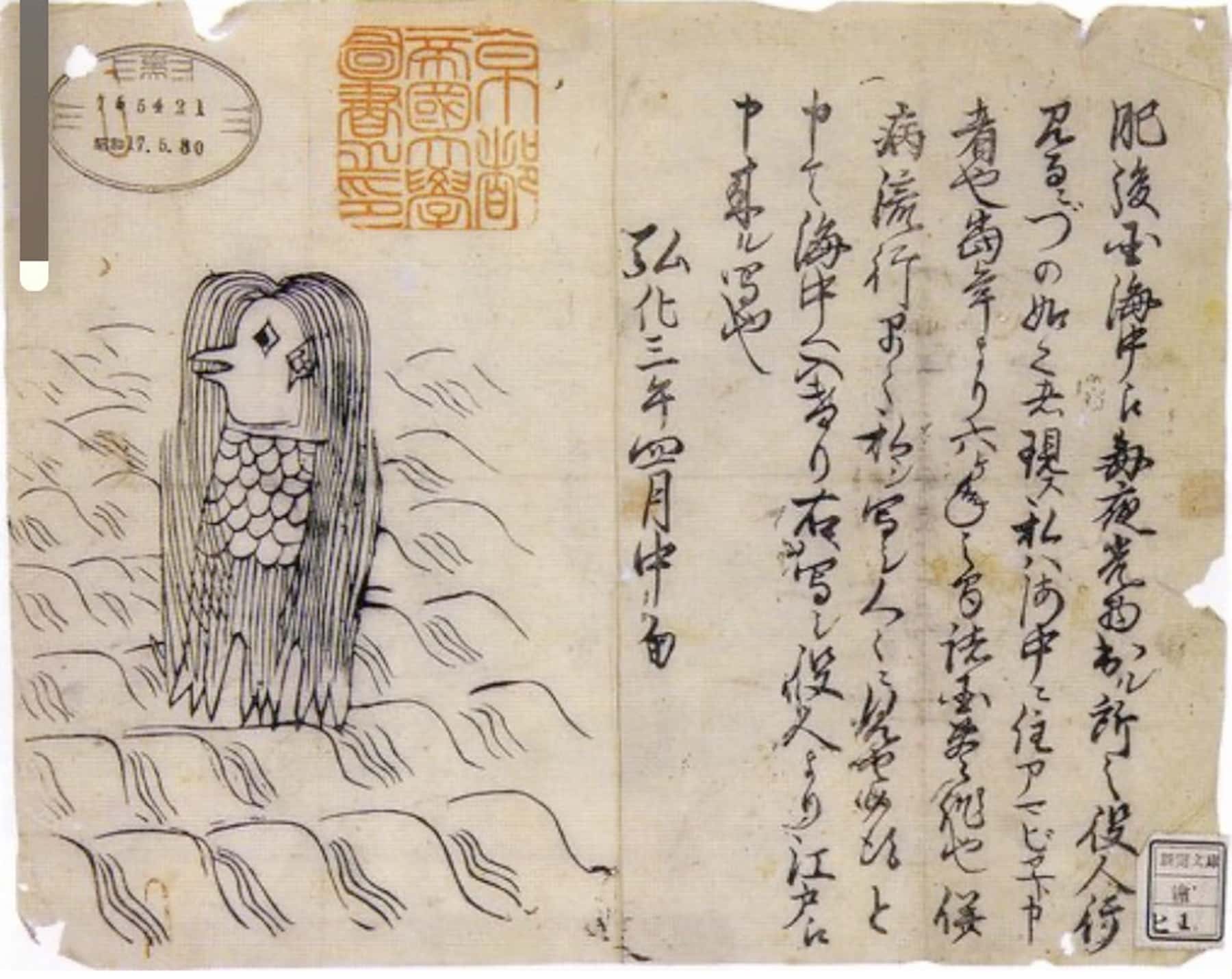

The curious encounter was published by the local newspaper, accompanied by a woodblock print of Amabie’s likeness, which helped to disseminate its image across Japan. The legend of Amabie remained dormant for much of the past 174 years, until the coronavirus swept across Japan. Over the past several weeks, its image has resurfaced on social media. The display has brought hope to those who share it, that they are helping to end the current pandemic.

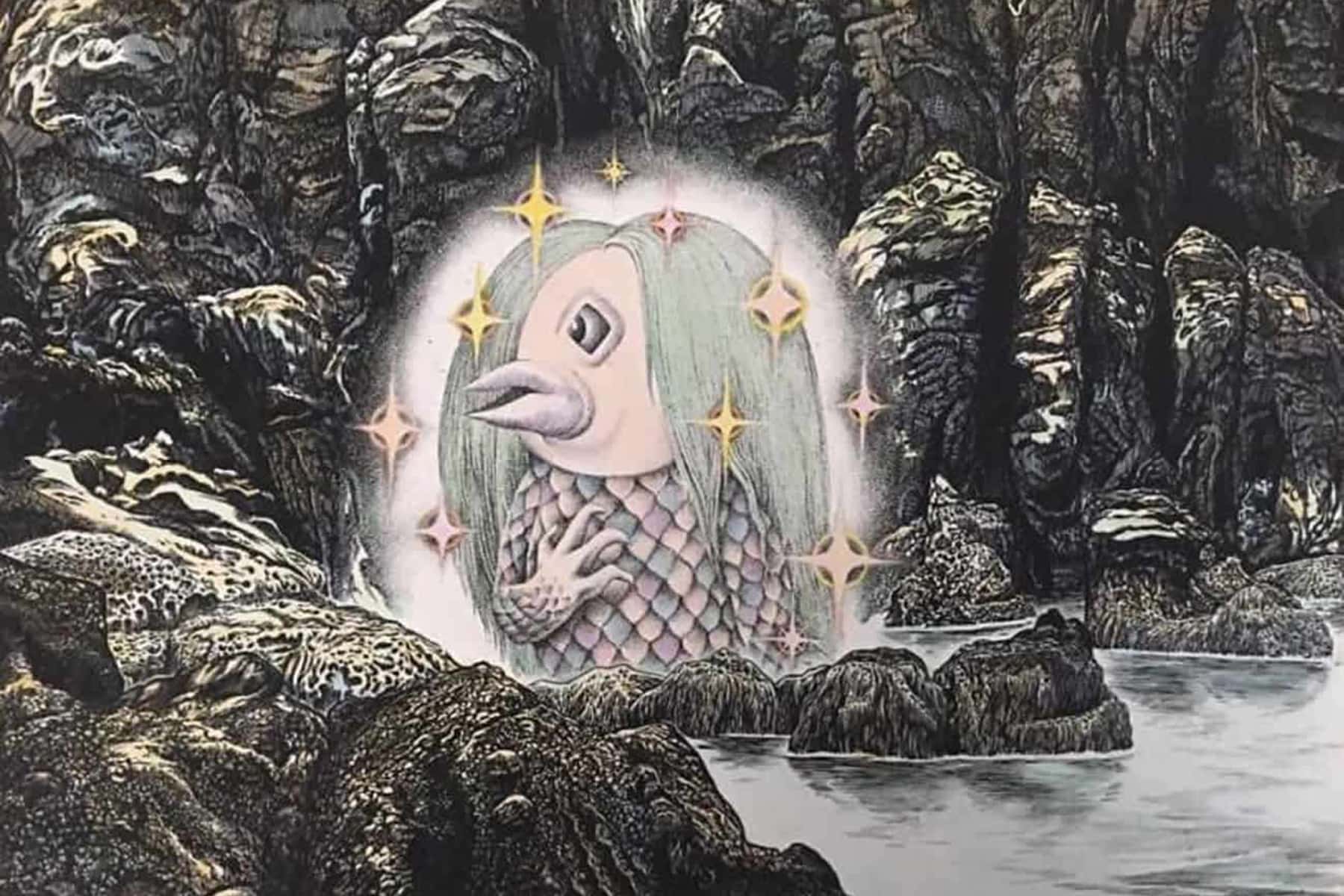

On March 6, Kyoto University Library posted on its Twitter account a picture of the original news sheet dated April 1846, with an illustration of an Amabie and a description beside it. The piece was in its digital archive. A drawing of the monster by the late manga artist Shigeru Mizuki (1922-2015), known for his manga about Japanese yōkai, was also released on the Mizuki Production Twitter account on March 17 with the message “May the modern-day plague go away.”

“Yōkai are the carriers of historical memory of the Japanese people,” said Victoria Rahbar, a graduate student at Stanford University’s Center for East Asian Studies. “They are not static, with new ones popping up occasionally thanks to new documentation of them being found or due to the work of Japanese manga masters like Shigeru Mizuki,” whose manga franchise GeGeGe no Kitaro helped to not only revive yōkai characters in the 1960s, but also to transform them into more lovable and less-feared characters.

Social media users have continued to post personalized depictions of Amabie in a variety of forms across Twitter and Instagram, including clay figurines, embroidery, paper cutouts, bowls of udon noodles, bento lunch boxes, fashion wear – including face masks, and illustrations. Hashtags such as #amabiechallenge and #amabieforeveryone are also trending, with supportive phrases wishing for an early end to the ongoing pandemic.

Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare recently enlisted the apparition for an awareness flyer it tweeted in April, urging people to “stop the spread of infection.” The message reiterated Amabie’s original sentiment and validated its representation. Companies and entrepreneurs in Japan have also started using Amabie to sell product like “healthy” pudding, adorable demon donuts, and Amabie IPA beer.

The hope and sometimes humor that goes along with each depictions are very personal. The effort has made Amabie into a unifying force for Japan, by reaching deep into its obscure national past to find solace during an uncertain time. If only America could discover a similar focus to replace its divisive cartoon mascot currently posing as a national leader.

© Photo

Lee Matz