Honeybees were introduced to America by European settlers in the 16th century and became indispensable to modern agriculture. In Milwaukee, that relationship has been exemplified by the apiary at Forest Home Cemetery, a unique urban sanctuary for essential pollinators.

“Bees have pollinated a wide variety of native plants and helped create nature’s ecosystem, but without honeybees our food system would collapse and billions would die of malnutrition,” said Chad Nelson, an apiculturist and co-founder of Fairy Garden Hives.

Honeybees have a unique ability to survive over the winter and can be transported from one blooming crop to another, setting them apart from other bee species. Adaptability made them the backbone of large-scale monoculture agribusiness.

However, the expansion of such practices significantly reduced floral diversity, making urban landscapes like Forest Home Cemetery some of the last refuges for both honeybees and native pollinators. Urban sanctuaries have become crucial for supporting diverse bee populations amid the decline of rural floral habitats.

“Whether we keep honeybee hives, plant native bee flowers, or just integrate clover into our lawns, we all should be doing something with bees in mind,” Nelson said. “Buy local, grow your own, avoid using chemicals on your property, and nativize your lawn to create a more hospitable environment for bees.”

Milwaukee passed a beekeeping ordinance in 2010 allowing individuals to practice beekeeping in the urban center of the city. Since then, the efforts at Forest Home Cemetery have served as a model for urban beekeeping and conservation, demonstrating how city dwellers can contribute to bee health.

The process of making honey begins with worker bees gathering nectar, a sugary liquid produced by flowers to attract pollinators. Bees use their long tongues to collect the nectar, storing it in a special part of their bodies called the “honey stomach.”

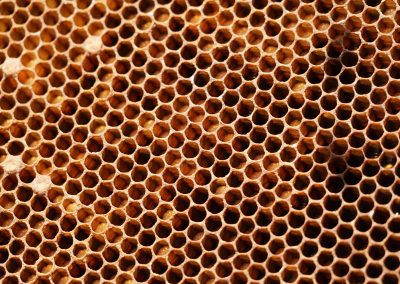

Once full, they return to the hive and pass the nectar to other worker bees, who chew it and mix it with enzymes. This process breaks down complex sugars into simpler ones, making the nectar easier to digest and less prone to crystallization. The partially transformed nectar is then deposited into honeycomb cells, where bees fan it with their wings to evaporate the water content, thickening it into honey.

The reduction of water content is crucial because it prevents fermentation and spoilage, ensuring the honey can be stored for long periods. The process of fanning and evaporating water can take several days, depending on the humidity and temperature inside the hive.

As the nectar thickens and transforms into honey, it becomes more viscous and develops the characteristic sweet taste. Once the honey reaches the right consistency and has less than 18% water content, bees seal the honeycomb cells with a wax cap.

The capping is done with beeswax, which the bees produce from glands on their abdomen. The wax cap protects the honey from air and moisture, allowing it to be stored indefinitely without spoiling. The sealed honeycomb cells serve as a food reserve for the bee colony, especially during times when nectar is scarce, such as in the winter. Honey provides bees with the necessary energy to survive during periods when foraging is not possible.

Another intriguing aspect of this process is the role of electricity. Bees become positively charged as they fly through the air due to triboelectric charging, which is similar to the static electricity that makes your hair stand on end when you rub a balloon against it.

This positive charge is spread across the fine hairs on their bodies, making honeybees excellent at attracting negatively charged particles, like pollen. Flowers, on the other hand, often have a slight negative charge on their surfaces, influenced by factors such as soil, water, and atmospheric conditions.

When a positively charged bee approaches a negatively charged flower, the difference in electrical potential creates an attraction that helps pollen grains stick to the bee’s body. As bees move from flower to flower, they transfer pollen and facilitate cross-pollination and fertilization, which is vital for plant reproduction and the health of ecosystems.

In addition, bees can detect if a flower has already been visited by another bee. When a bee collects nectar, it slightly changes the electrical charge of the flower by discharging some of its positive charge onto it.

Bees are sensitive to these changes and can sense if a flower’s charge has shifted, indicating that its nectar supply might be depleted. They use tiny mechanoreceptors called sensilla on their antennae and bodies to detect these changes in the electrical field.

“Native pollinators are truly the bees that are in trouble, losing species at 20% a year,” said Nelson. “Honeybees are bred for modern agriculture and have become essentially domesticated livestock. They are not going extinct as fast as the native bees.”

Urban initiatives, like the Silent City Honey Farm at Forest Home Cemetery, illustrate how communities can support populations of essential pollinators. By promoting floral diversity and reducing chemical usage, individuals can help mitigate the decline of native bee species and ensure the stability of local food systems around Milwaukee.