I accepted photojournalism assignments with connections in Milwaukee to some of the most volatile places in the world last year. In the moments when I could step back from the trauma and clear my mind, I often found those brief moments of solitude in ancient places of worship.

At the core of all the “Great Faiths” is the concept of treating others with kindness and respect. Regardless of the expression, ritual, language, or belief, in my experience – it all comes down to love. And so I always find it calming to visit any place built for a community of people to express their faith and share their love.

St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Cathedral in Milwaukee is one such place.

In 2023, I visited three sacred places that had at one time been the pinnacle of Orthodox Christianity in their day. Saint-Sophia Cathedral, which symbolized the “new Constantinople” capital of the Christian principality of Kyiv. Hagia Sophia was originally built as the principal basilica of the Byzantine Empire, but later transformed into the Ayasofya Grand Mosque after Constantinople became Istanbul. And the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, one of the most sacred sites in Christianity and revered as the place of Jesus Christ’s crucifixion, burial, and resurrection.

I took thousands of photos at each location, admired the architecture, marveled at the craftsmanship of the adorning artwork, and tried to wrap my head about not just the centuries of history within their walls but the generations of worshipers – and the stories of each one of those countless lives who loved God by whatever name.

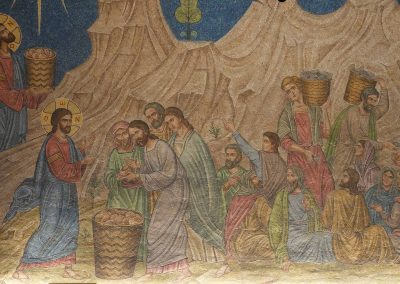

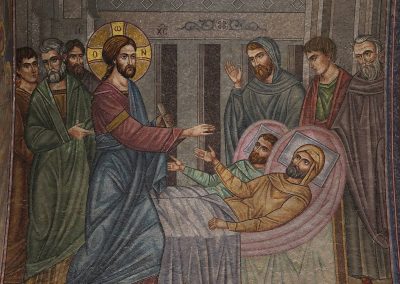

On a spiritual level, those experiences made me feel really small yet connected to everything at the same time. On a professional level, I felt overwhelmed by just the details of what I saw. so I disconnected my brain before it could try and calculate all the tiles cut and placed by hand into their mosaics of honoring faith.

It was by using instinct that I navigated those spiritual journeys. The beauty for me was the “voyage of discovery.” I did not do extensive research in advance, because I always feel it creates a checklist. When people rush to see something, they often accomplish it without actually seeing anything. And as a photojournalist, I have to do a lot of observation. When I look, I want to see the story being told to me before someone explains it.

My first introduction to St. Sava came in 2017. That May, I traveled all over Milwaukee to photograph memorials dedicated to the Medal of Honor recipient, U.S. Air Force pilot Lance Sijan. The assignment was for a series about the Sijan Memorial Plaza that was scheduled to open at Mitchell International Airport. It featured a replica of the F-4 Phantom he flew in Vietnam.

Sijan is beloved in many communities, but specifically by Serbian Americans. His father was an ethnic Serb who emigrated from Serbia during World War I. A memorial that honors Sijan can be found on the grounds of St. Sava. However, I did not have the opportunity to enter the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral. Seven years later I found myself back on those grounds, now covered with the snow of January.

Entering St. Sava had the familiar feel of when I stepped into the Orthodox world overseas, and it was oddly nostalgic. After the Slava of St. Sava started, I had a couple of unexpected realizations.

Everyone was standing for a very long time, which I later learned was a tradition for special celebration services. It also explained why I saw Orthodox churches in Europe without pews.

But what really struck me was being in an Orthodox church that was alive. It was not a museum full of tourists, but people who lived near each other in Milwaukee. It was a thriving community.

It is a universal irritation when children cry during a church service. But for me, it was actually refreshing to hear that a couple of times. It means the church has life, it has a future. I have been to so many silent churches for worship, empty of children and grandchildren.

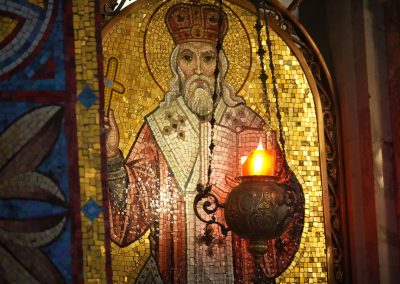

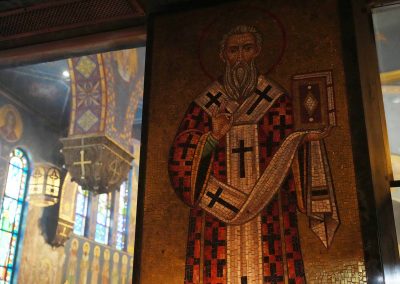

Most of the Serbian community in Milwaukee is centered around St. Sava at 51st Street and Oklahoma Avenue. The St. Sava Milwaukee-Kragujevac Sister Cities Committee explained to me that the cathedral building is known for its architecture and elaborate wall mosaics, depicting stories from the Bible.

Founded in 1912, the cathedral was established as a spiritual home for the growing Serbian population in Milwaukee. During the early 1950s, there was a significant increase in Serbian immigration, which contributed to expansion efforts. Recognizing the need for a larger place of worship, the congregation decided in 1951 to start preparations for building a new church. That led to the construction of the cathedral of St. Sava in 1956, designed in the Serbo-Byzantine style.

Serbs remain very active in the local community. Serbian Days, which takes place every August, is a staple of Milwaukee’s festival season and features homemade Serbian delicacies such as burek, cevapi, and sarma, as well as performances by folk dancers. And, most Milwaukeens know American Serb Hall for its fish fry and presidential visits.

While the early waves of Serbian immigration were primarily for economic reasons, the later waves happened as a result of conflict. One began after World War II and the Communist takeover of Yugoslavia. A later wave began in the 1990s as Yugoslavia came apart, forcing Serbians to flee to Milwaukee to escape the instability surrounding that violence.

By January 1992, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia ceased to exist. Its successor States became Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, and Slovenia. The breakup of Yugoslavia led to a series of conflicts in the 1990s, including the Bosnian War (1992-1995) and the Kosovo War (1998-1999).

The conflicts created a significant number of refugees and displaced families. Many Serbians sought refuge in various parts of the world, including Milwaukee with its long-established Serbian diaspora.

On January 27, the St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Cathedral in Milwaukee held the “Slava of St. Sava.”

The Slava is a unique Serbian custom where families annually celebrate their patron saint’s feast day. In the Serbian Orthodox tradition, each family has its own patron saint, passed down through generations.

The day is marked with special ceremonies, like when the family’s priest blesses the bread and the family, reinforcing religious and community ties. A festive meal includes the ceremonial bread called Slavski kolač and a koljivo, or wheat dish.

The January 27 Slava was particularly significant for the local community, because St. Sava is the founder of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Milwaukee.

St. Sava was the first Archbishop of the autocephalous Serbian Church, and an important figure in medieval Serbia. St. Sava is highly revered in Serbian history and the Orthodox Christian faith for his role in establishing the Serbian church, and his contributions to Serbian law and education.

Among the many local families and dignitaries who attended the Slava was Kragujevac’s Mayor, Nikola Dašić. His delegation formally signed the Sister City agreement with Milwaukee on January 26.

Damjan Jovic, General Consul of the Republic of Serbia in Chicago, attended the Slava along with Bishop Longin – who also traveled from Illinois. Bishop Longin is the Eparchy of New Gračanica and Midwestern America, and is one of the longest-serving Serbian Orthodox bishops. He was also the war-time Bishop of the Dalmatia region of Yugoslavia, before it became part of Croatia.

So it was funny, and with some honor, that when I finally spoke to Bishop Longin at the end of the Slava, he said that he thought I came with the press group from Serbia. He did not realize I was from Milwaukee, and that I was not Serbian.

His comment reminded me of what Alderwoman Marina Dimitrijevic had said during the Sister City signing event, and echoed by so many speakers. That is … “we are all family, and we are all Serbian.”

© PHOTO NOTE: All the original editorial images published here have been posted to mkeind.com/facebook. That Facebook collection of photos contains the Milwaukee Independent copyright and watermark for attribution, and may be used for private social media sharing. Do not download and repost images directly from this page.

- Strength of immigrant roots: How Marina Dimitrijevic builds a cultural bridge between Milwaukee and Serbia

- Serbia’s Kragujevac sees a new chapter of international cooperation with Milwaukee as a Sister City

- The Slava of St. Sava: A photographic journey into the experience of Serbian Orthodox faith in Milwaukee

- A nation at the crossroads: Understanding the global impact of Serbia’s internal political discontent

Lee Matz