The Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) is a complex, multi-layered border region between North and South Korea, designed to prevent direct military confrontation while preserving a buffer zone of separation between the two countries.

The DMZ is 160 miles long and roughly 2.5 miles wide. After more than 70 years it is still regarded as one of the most heavily fortified and tension-filled borders in the world, even though it was established as a peaceful demilitarized area following the Korean War (1950-1953).

In September, Milwaukee Independent visited about 30% of the DMZ, from Goseong and the “Punchbowl” in the east to Odusan, Dora, Imjingak, and Paju in the west. The Punchbowl area is commonly known for the battle of Heartbreak Ridge, which was the basis of Clint Eastwood’s 1986 movie.

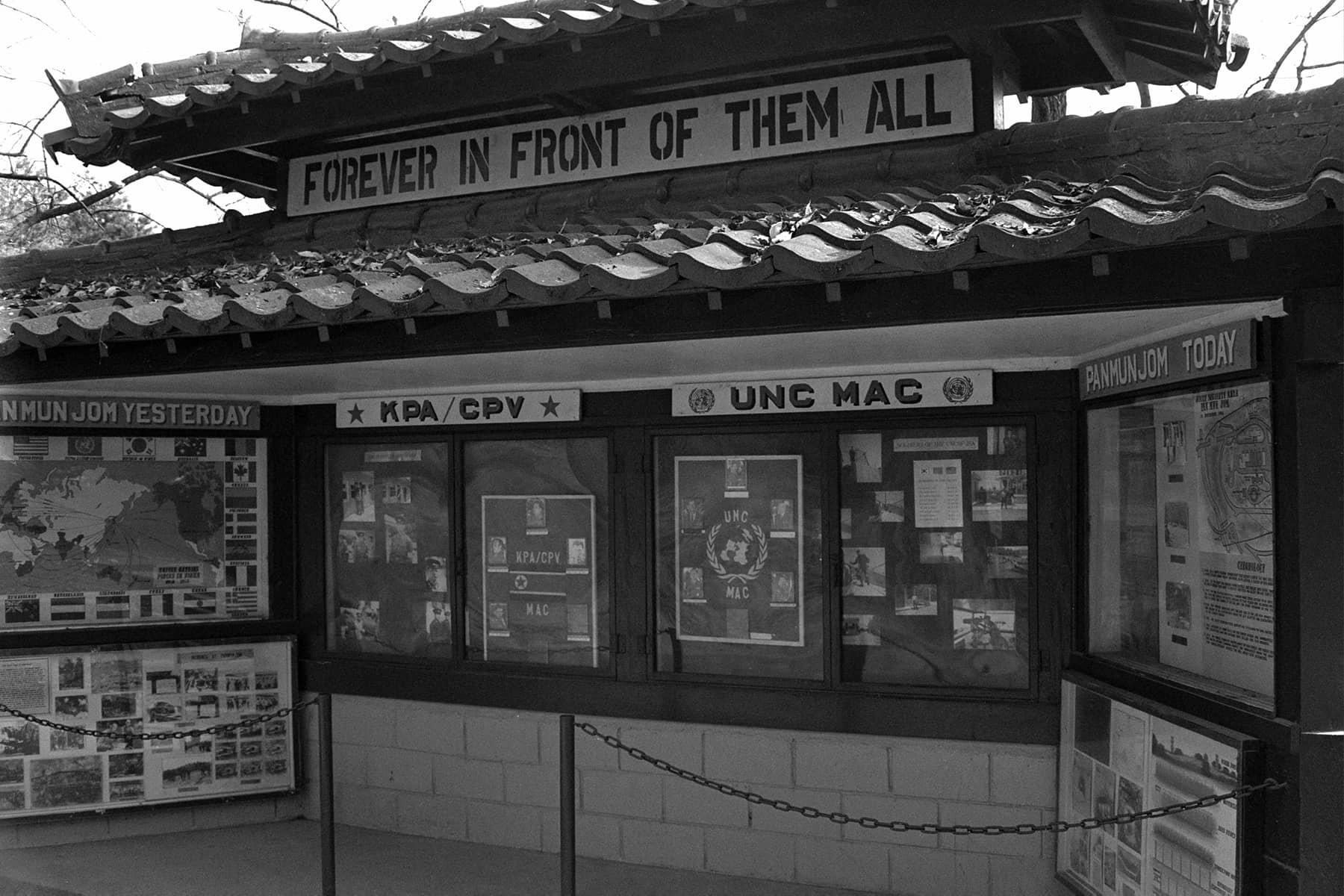

The iconic Joint Security Area (JSA) at Panmunjom has been closed to the public since July 2023, following the high-profile incident where U.S. soldier Travis King crossed the border into North Korea during a group tour. The United Nations Command (UNC) suspended all tour programs to the area as a security measure and has yet to resume access.

Long before he was the Senior Photojournalist for Milwaukee Independent, Lee Matz visited the site in 1996. He once described the experience as watching a well-choreographed dance, so repetitive and commonplace that it disguised the hostility always boiling just under the service.

During that visit, he also stood in North Korea – but within a UNC conference hut. Used for negotiations between North and South Korea, the powder blue buildings are located directly on the Military Demarcation Line (MDL), which serves as the border between the two countries.

Inside these huts, the MDL runs through the middle of the conference table, with one side of it sitting on the South Korean side and the other in North Korea. A cable from a microphone is considered the actual division line. Visitors who participate in JSA tours can briefly cross into North Korean territory while inside the UNC building. It is one of the only places where people can technically “stand” in North Korea without crossing the heavily fortified DMZ.

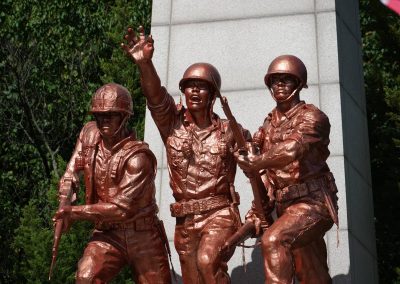

With 1.2 million North Korean soldiers facing some 600,000 South Korean and American troops, the DMZ has grown into a paradoxical region. It is simultaneously a symbol of division and conflict, but also an area that has attracted tourists and is seen by some as a potential platform for reunification or peace.

ORIGINS OF THE DMZ

The Korean Peninsula was divided along the 38th parallel after World War II, following the defeat of Japan, which had occupied Korea for 35 years. The division placed the Soviet Union in control of the northern half and the United States in charge of the southern half. The unfortunate result was the formation of two separate governments: the communist Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) under Kim Il Sung and the democratic Republic of Korea (South Korea), under President Syngman Rhee.

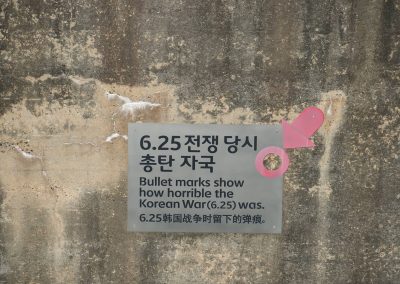

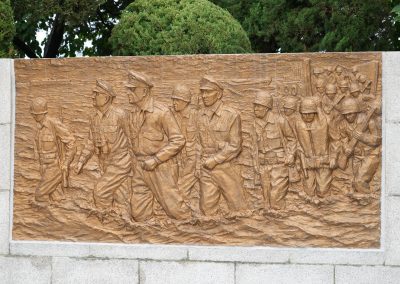

The ideological differences quickly escalated into full-scale warfare when North Korean forces invaded South Korea in 1950, marking the beginning of the Korean War. After three years of fighting and millions of casualties, an armistice agreement was signed on July 27, 1953. The agreement established the DMZ as a buffer between the two Koreas. Technically, the two countries are still at war since no formal peace treaty has ever been signed.

The DMZ itself follows the general path of the 38th parallel, though it deviates slightly along certain portions. The key boundary areas within and around the DMZ are as follows:

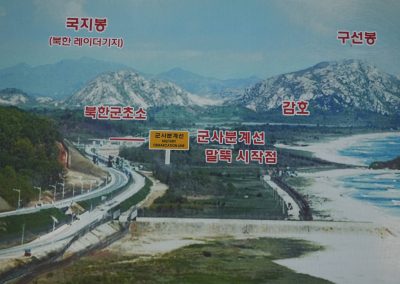

Military Demarcation Line (MDL): the actual border or “line” separating North Korea (the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, DPRK) and South Korea (the Republic of Korea, ROK) within the DMZ.

Demilitarized Zone (DMZ): a buffer zone created to keep the forces of North and South Korea apart. The primary purpose of the DMZ is to prevent direct military engagement between the two Koreas by creating a neutral area where neither side’s military forces can enter or operate. The zone is fortified by fences, landmines, and observation posts on both sides, despite being labeled as “demilitarized.”

Joint Security Area (JSA) / Panmunjom: a small sector within the DMZ where North and South Korean forces face each other directly. It is the only part of the DMZ where North Korean and South Korean soldiers stand within a few meters of each other, though they are stationed on their respective sides of the MDL. The JSA is also the location for diplomatic engagements and negotiations between the two Koreas and the United Nations Command. It has witnessed significant events such as armistice talks and inter-Korean summits.

Civilian Control Line (CCL): a boundary set up in South Korea outside the southern edge of the DMZ. It restricts civilian access to areas directly adjacent to the DMZ to ensure security and prevent unauthorized entry into the sensitive border zone. The CCL runs parallel to the southern boundary of the DMZ, typically located several miles south of the actual DMZ itself.

Southern Limit Line (SLL) and Northern Limit Line (NLL): are maritime boundaries that extend off the coast from the DMZ into the Yellow Sea on the west coast and East Sea on the east coast. These lines delineate the respective maritime territories of North and South Korea.

SECURITY MEASURES

Fences and Barriers: The DMZ is surrounded by extensive fencing, including barbed wire and electrified barriers. These fences are supplemented by a series of security measures such as motion sensors and surveillance cameras.

Landmines: The area is heavily mined, with an estimated 1 to 2 million landmines buried along the DMZ, making it one of the most heavily mined regions in the world. Both North and South Korea have planted mines to prevent unauthorized crossings.

Guard Posts and Watchtowers: The DMZ features numerous sentry posts on both sides. The South Korean side is protected by a network of military bases and observation posts, while the North Korean side has similar installations, including heavily fortified bunkers and artillery positions.

Although the DMZ spans the entire Korean Peninsula, there are certain sections that are particularly special. While Panmunjom is the most famous location in the DMZ, there are several other significant sites with historical, strategic, or ecological importance. These locations serve various purposes such as military significance, tourism, historical memory, and environmental conservation.

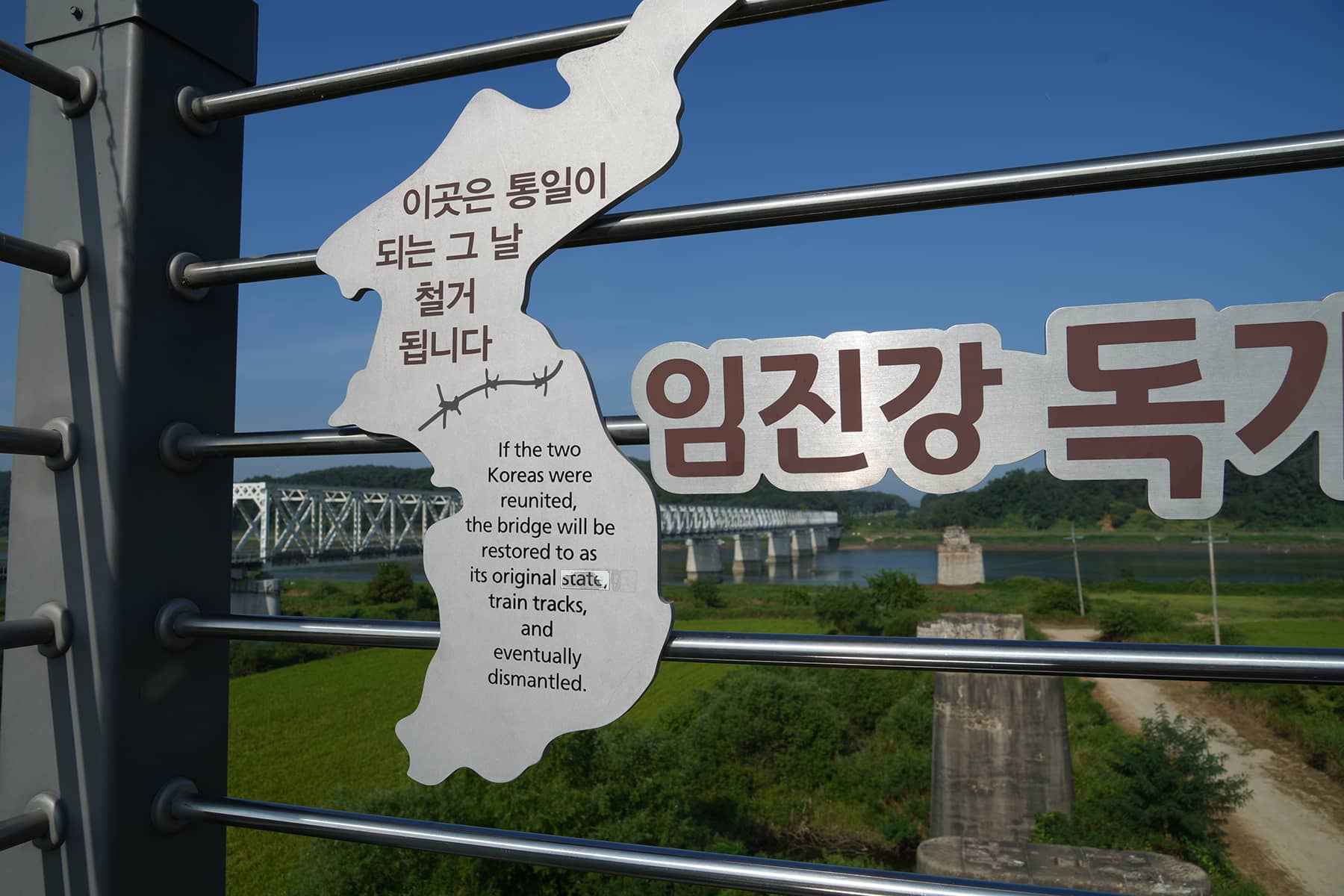

The Freedom Bridge: This iconic bridge near the western end of the DMZ was used by prisoners of war to return to South Korea after the armistice was signed. It stands as a reminder of the painful separations and longing for reunification that continues to define the Korean Peninsula.

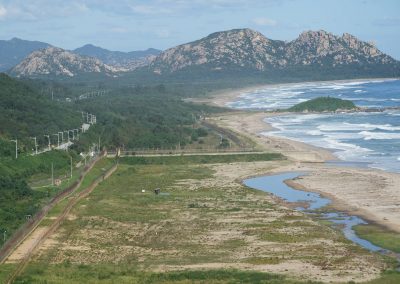

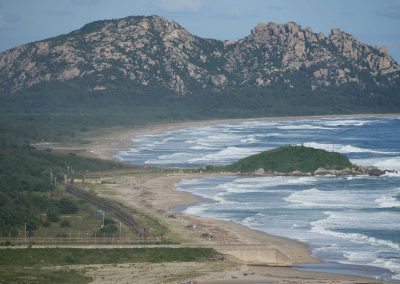

Goseong Unification Observatory is situated on the eastern coast of the Korean Peninsula, it offers one of the closest views of North Korean territory. This area was a frontline during the Korean War.

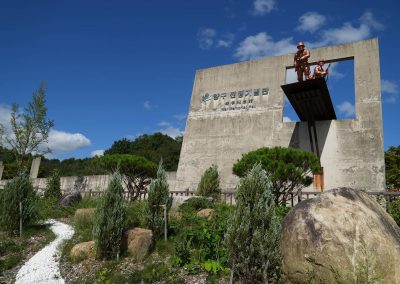

The Punchbowl, located in Yanggu County, is a large, bowl-shaped valley formed by a volcanic crater. During the Korean War, it was the site of intense fighting between U.N. forces and the North Korean Army. The area became strategically important because of its high terrain, offering commanding views of the surrounding areas.

The Odusan Unification Observatory sits at the confluence of the Han and Imjin rivers, where visitors can view North Korean villages across the water. This observatory is unique because it showcases the stark contrast between the two Koreas in close proximity. Through binoculars, visitors can observe everyday life in North Korean farming communities.

The Dora Observatory is located near the western section of the DMZ and offers one of the best vantage points into North Korea, including the industrial town of Kaesong and the surrounding landscapes.

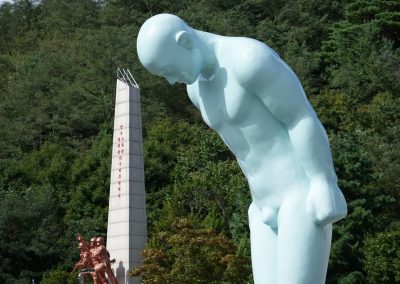

Imjingak is a large park and memorial site located near the Imjin River, just south of the DMZ. It was built to console the families of those displaced from North Korea and is packed with monuments, such as the Mangbaedan, where South Koreans can perform ancestral rites for relatives in the North.

Paju is a city that acts as the gateway to several DMZ-related attractions, including Dora Observatory, Dorasan Station, and Imjingak Park. In addition to these historical landmarks, Paju is known for its DMZ Peace Trail, a walking route that allows visitors to get closer to the heavily fortified border while learning about the history of the Korean War and the efforts toward peace and reconciliation.

The Third Infiltration Tunnel is an underground passage built by North Korea for potential surprise attacks on South Korea. Discovered in 1978, it is located near Paju in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). It is one of four known tunnels constructed by North Korea.

Despite its militarized nature, the DMZ has also become a popular destination for tourists, both domestic and international. Tourism to the DMZ from the South Korean side began in earnest in the 1990s, following several periods of diplomatic thaw between the two Koreas. Today, the DMZ is one of the most visited sites in South Korea, drawing more than a million tourists annually before the COVID-19 pandemic.

ECOLOGICAL SANCTUARY

Ironically, the very same restrictions on human activity that have made the DMZ one of the most heavily fortified places in the world have also allowed it to become one of the most well-preserved ecosystems on the Korean Peninsula. With almost no civilian settlements or agricultural activities inside the zone, the DMZ has become a de facto nature reserve, home to a wide variety of plant and animal species, some of which are endangered.

ONGOING TENSIONS

Despite the occasional symbolic gestures of peace, such as the summits between North and South Korean leaders in 2000 and 2018, the DMZ remains a zone of intense tension. The situation is exacerbated by the nuclear ambitions of North Korea and its volatile leadership. While the two Koreas have engaged in several rounds of high-level talks aimed at reducing tensions, sporadic incidents along the DMZ, such as shootings, defections, and propaganda broadcasts, underscore the fragility of the decades-old armistice.

In 2020, North Korea demolished the inter-Korean liaison office in Kaesong, a city near the DMZ, as a sign of frustration with the stalled diplomatic process. Around the same time, North Korean defectors were reported to have sent balloons carrying anti-regime leaflets across the DMZ into North Korean territory, further aggravating tensions.

These incidents illustrate how, even after many years of relative stability, the DMZ remains a hotbed of geopolitical uncertainty. The presence of U.S. troops in South Korea, the ongoing military exercises between South Korea and its allies, and the ever-present possibility of miscalculations or provocations from the North contribute to the sense that the DMZ could erupt into conflict once more at any time.

A SYMBOL OF DIVISION AND HOPE

The Korean DMZ serves as a powerful symbol of both the enduring division between North and South Korea and the persistent hope for reunification. While the DMZ is defined by its history of violence and its present state of militarization, it is also a reminder of the importance of diplomacy and the potential for peace. For now, it remains an ambiguous space, a place where soldiers stand on constant alert, yet where tourists take selfies, and endangered species find refuge.

MI Staff (Korea)

Lее Mаtz

Holger Kleine, Loes Kieboom, Yllyso, Meeh, and 26DaysOff (via Shutterstock)

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

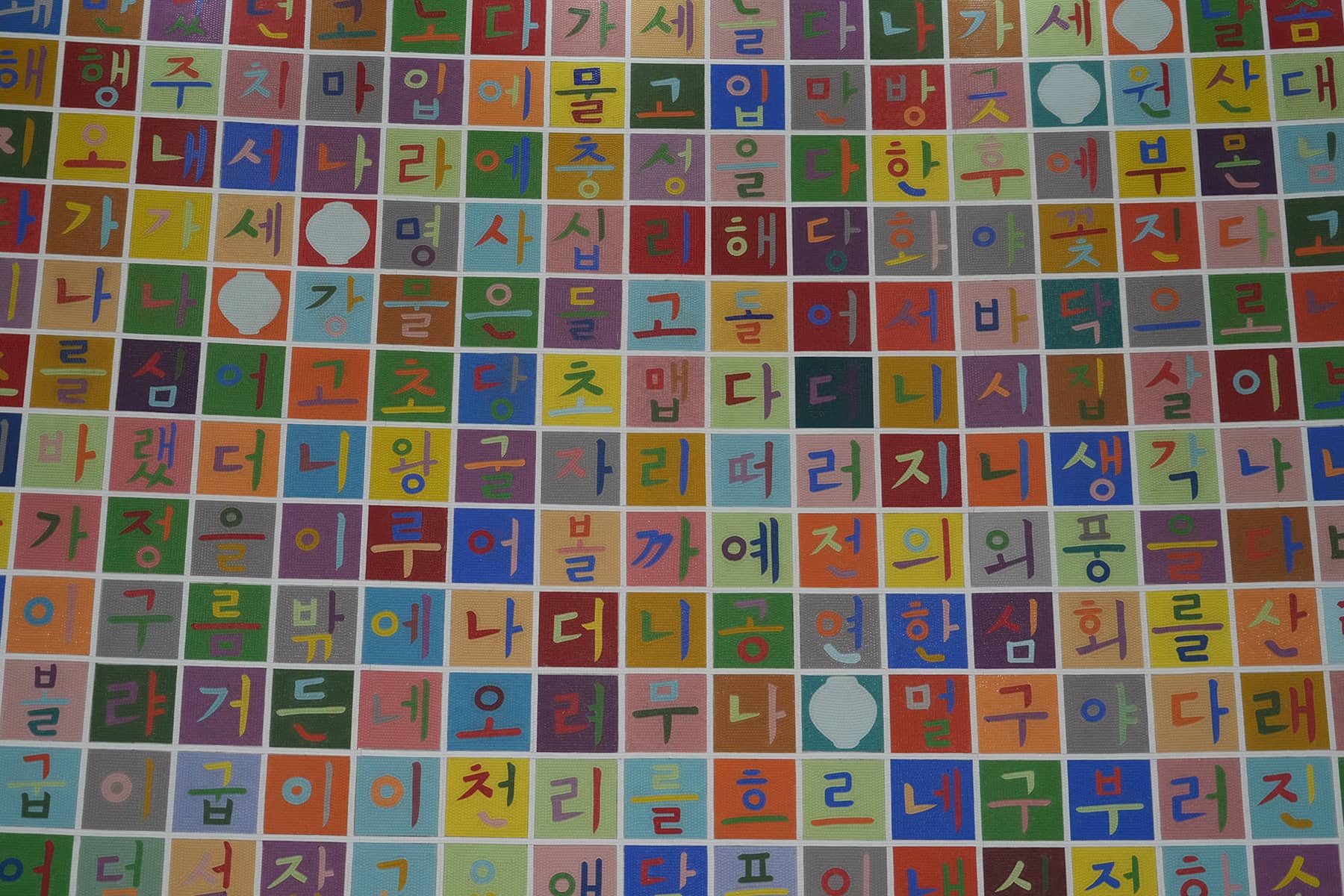

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora