Nearly two centuries after his brief life and brutal death were entered into public record as the only recorded lynching in Milwaukee history, George Marshall Clark’s unmarked grave was memorialized with a granite headstone during a special ceremony at Forest Home Cemetery on September 8.

The event marked the the 160th anniversary of his murder in 1861. City and cemetery records placed Clark’s remains at Forest Home. Local artist and activist Tyrone MackLee Randle Jr. identified the exact location of Clark’s unmarked grave in consultation with Forest Home staff, bringing Clark’s story to wider attention following racial-justice protests in the summer of 2020.

A joint fundraising effort by Forest Home Cemetery and Randle secured funds for Clark’s headstone last spring. The headstone was crafted from what is called “American Black” Granite, and came from a Pennsylvania quarry – the same state where Clark was born.

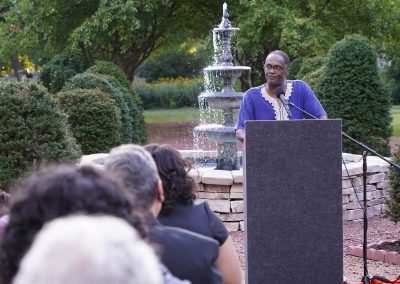

“America’s Black Holocaust Museum is uniquely positioned to help acknowledge the life of George Marshall Clark and the tragic events of his death as a charge of our mission. Our founder, Dr. James Cameron, dedicated his life to educating about racial violence and the terror of lynching, which he himself survived,” said Dr. Robert Davis, President and CEO of Black Holocaust Museum (ABHM). “The events of September 7 and 8, 1861 were unfortunately all too common across this nation, where lawless mobs deputized themselves and inflicted egregious harm on Black individuals and communities. ABHM is thankful to join with Forest Home Cemetery and the community in finally memorializing the life and lynching of George Marshall Clark and reconciling with what that means 160 years later.”

America’s Black Holocaust Museum was founded by lynching survivor Dr. James Cameron in 1988 to educate the world about the history of African Americans from pre-captivity to the present as an integral part of U.S. history. Rooted in themes of Remembrance, Resistance, Redemption, and Reconciliation, our collections cover more than 400 years of history with primary goals of educating and creating space for racial repair, reconciliation, and healing.

“George Marshall Clark died an innocent young man when his safety and dignity as a Black man were utterly denied him,” said Sara Tomilin, Forest Home Cemetery Assistant Executive Director. “As Milwaukeeans, we owe it to all young people in our community, and to the memory of Mr. Clark, to properly acknowledge this lynching. We cannot risk forgetting Clark’s life or death. We’re grateful to America’s Black Holocaust Museum and to Mr. Randle for joining us to pay Mr. Clark proper tribute and to share his story.”

Forest Home Cemetery was established in 1850 as a cemetery for the city of Milwaukee by St Paul’s Episcopal Church. It was managed by the church until 2012, when it became an independent nonprofit. But for 171 years, members of the congregation have remained on its board of directors. Over that time, the cemetery expanded to just under 200 acres and became the final resting place for 26 mayors, more than 1,000 Civil War veterans, and countless prominent people who left their mark on Milwaukee.

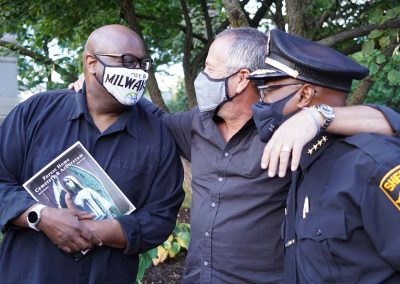

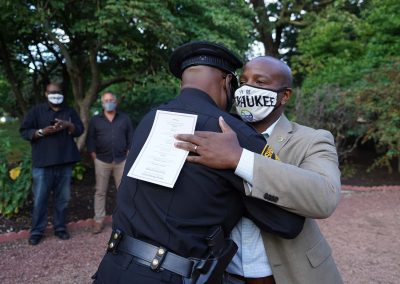

Alderwoman JoCasta Zamarripa, Milwaukee Independent’s Senior Columnist Reggie Jackson, Marquette University’s Dr. Robert Smith, Pardeep Singh Kaleka, Executive Director for the Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee, and Milwaukee County Executive David Crowley spoke at the dedication ceremony.

HOW A LYNCHING TOOK PLACE IN MILWAUKEE DURING THE CIVIL WAR

It was evening, September 6, 1861, when housemates James Shelton and George Marshall Clark strolled downtown Milwaukee with two friends. Records say that Shelton possessed “a quiet, orderly disposition.” His friend, “Marshall, was an apprentice barber under his father George H. Clark, a leader of the city’s small Black community.

The evening turned when Dabney Carney, a known instigator, and John Brady voiced displeasure with the foursome, referring to them as “damned niggers,” almost assuredly because these Black men were consorting with White women. The four men began a fight that ended only after Shelton stabbed Carney in the abdomen and slashed Brady.

Clark and Shelton were captured and locked in the county jail on Cathedral Square. Carney identified Shelton as his assailant before dying of his injuries on September 7. Carney’s death coincided with the first anniversary of the Lady Elgin shipwreck that claimed the lives of 300 Irish Union Guard and family in 1860, reigniting the community’s grief and anger.

News of Carney’s death spread through the Third Ward’s Irish population quickly, setting off a literal alarm that amassed an angry mob. The mob stormed the jail, injuring law enforcement standing guard, forcing the jailer to lock the main doors. The mob needed only 18 blows to destroy the iron doors. Shelton hid. Marshall did not, protesting his innocence as the mob beat and dragged him to the Third Ward.

He emerged from a brief “fair and lawful trail” at a nearby courthouse with a noose around his neck. Arriving at Water and Buffalo Streets, the mob found a pile driver and secured a rope to its top. At 2:30 a.m., they shoved Marshall off a ladder and left him there to swing for several hours.

History did not record who cut Marshall down, but likely it was his family. They brought his body to Forest Home Cemetery, where his name, birth and death dates, and the manner of his death – murder, can still be read in faded handwriting. Like many other lynching victims, Clark was buried in an unmarked grave. The Clark family left Milwaukee. Understandably, Black families often picked up and moved overnight from the site of a lynching, refugees from racial terror forced to leave behind jobs, property, family, and friends.

The Milwaukee Independent began reporting on George Marshall Clark’s story in 2017, and has since followed the public efforts to install a headstone at his grave and a historical marker where he was lynched, along with the history of lynching that still affects the Milwaukee community today. That collection of published news articles about Clark and other Black heroes who fought for freedom and equality during the Civil War can be found on a special George Marshall Clark and Milwaukee Lynchings landing page. mkeind.com/georgemarshallclark

© Photo

Lee Matz