For decades, the University of Pennsylvania has held hundreds of skulls that once were used to promote White supremacy through racist scientific research.

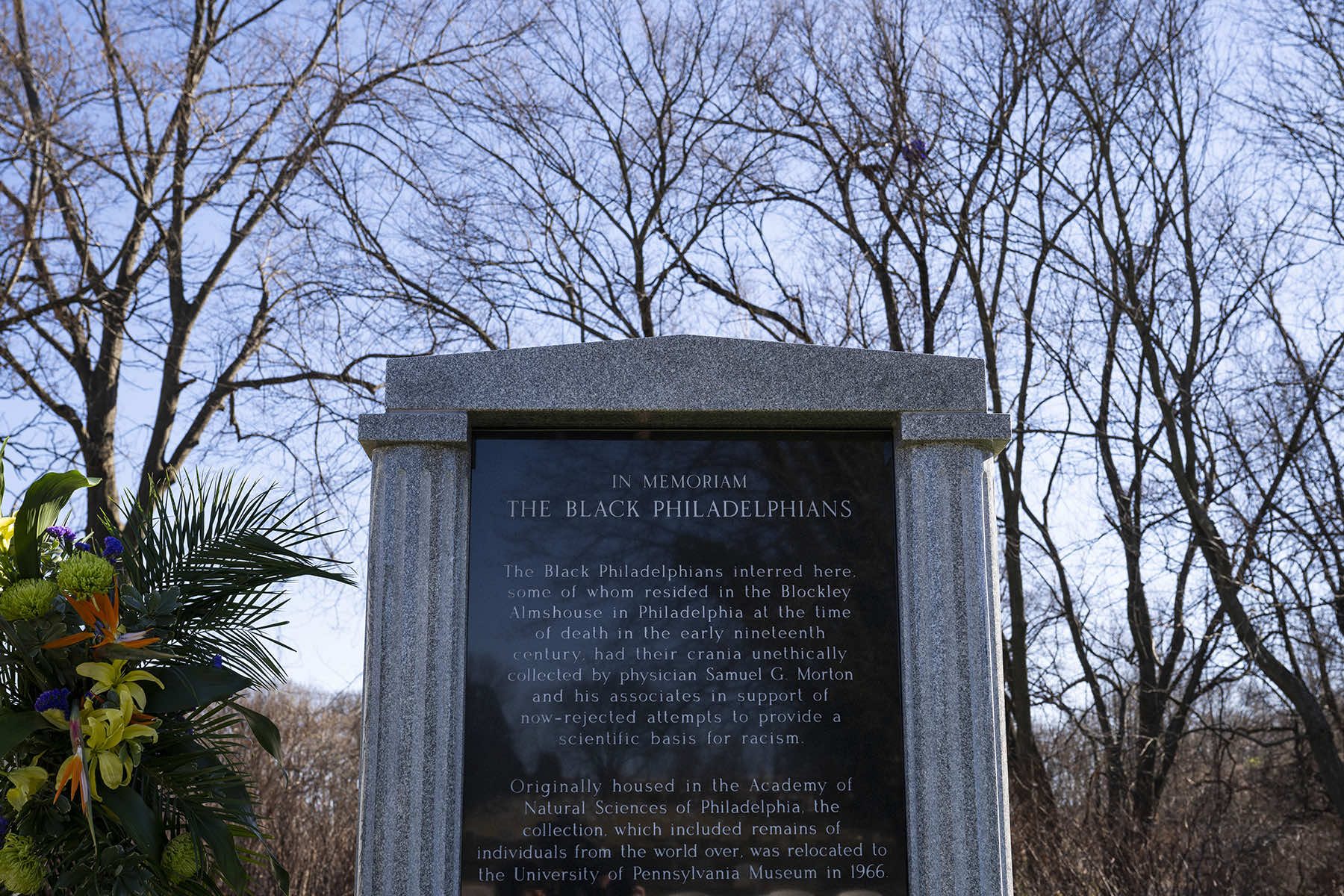

As part of a growing effort among museums to reevaluate the curation of human remains, the Ivy League school laid some of the remains to rest last week, specifically those identified as belonging to 19 Black Philadelphians. Officials held a memorial service for them on February 3.

The university says it is trying to begin rectifying past wrongs. But some community members feel excluded from the process, illustrating the challenges that institutions face in addressing institutional racism.

“Repatriation should be part of what the museum does, and we should embrace it,” said Christopher Woods, the museum’s director.

The university houses more than 1,000 human remains from all over the world, and Woods said repatriating those identified as from the local community felt like the best place to start.

Some leaders and advocates for the affected Black communities in Philadelphia have pushed back against the plan for years. They say the decision to reinter the remains in Eden Cemetery, a local historic Black cemetery, was made without their input.

West Philadelphia native and community activist aAliy A. Muhammad said justice isn’t just the university doing the right thing, it’s letting the community decide what that should look like.

“That’s not repatriation. We’re saying that Christopher Woods does not get to decide to do that,” Muhammad said. “The same institution that has been holding and exerting control for years over these captive ancestors is not the same institution that can give them ceremony.”

Woods told the crowd at the February 3 interfaith commemoration at the university’s Penn Museum that the identities of the 19 people were not recorded, but that the process of interment in above-ground mausoleums was “by design fully reversible if the facts and circumstances change.” If future research allows any of the remains to be identified and a claim is made, they can be “easily retrieved and entrusted to descendants,” he said.

“It will be a very happy day if we can return at least some of these fellow citizens to their descendants,” Woods said.

At a blessing and committal ceremony later at Eden Cemetery, about 10 miles southwest of the museum in Collingdale, Renee McBride Williams, a member of the community advisory group, said she was “relieved that finally the people who created the problem are finding a solution.”

“In my home growing up, when you made a mistake, you fixed it – you accepted responsibility for what you did,” she said.

“We may not know their names, but they lived, and they are remembered, and they will not be forgotten,” said the Rev. Charles Lattimore Howard, the university’s chaplain and vice president for social equity & community.

As the racial justice movement has swept across the country in recent years, many museums and universities have begun to prioritize the repatriation of collections that were either stolen or taken under unethical circumstances. But only one group of people often harmed by archaeology and anthropology, Native Americans, have a federal law that regulates this process.

In cases like that between the University of Pennsylvania and Black Philadelphians, institutions maintain control over the collections and how they are returned.

The remains of the Black Philadelphians were part of the Morton Cranial Collection at the Penn Museum. Beginning in the 1830s, physician and professor Samuel George Morton collected about 900 crania, and after his death the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia added hundreds more.

Morton’s goal with the collection was to prove — by measuring crania — that the races were actually different species of humans, with White being the superior species. His racist pseudoscience influenced generations of scientific research and was used to justify slavery in the antebellum South.

Morton also was a medical professor in Philadelphia, where most doctors of his time trained, said Lyra Monteiro, an anthropological archaeologist and professor at Rutgers University. The vestiges of his since-disproven work are still evident across the medical field, she said.

“Medical racism can really exist on the back of that,” Monteiro said. “His ideas became part of how medical students were trained.”

The collection has been housed at the university since 1966, and some of the remains were used for teaching as late as 2020. The university issued an apology in 2021 and revised its protocol for handling human remains.

The university also formed an advisory committee to decide next steps. The group decided to rebury the remains at Eden Cemetery. The following year, the university successfully petitioned the Philadelphia Orphans’ Court to allow the burial on the basis that the identities of all but one of the Black Philadelphians were unknown.

Critics note the advisory committee was comprised almost entirely of university officials and local religious leaders, rather than other community members.

Monteiro and other researchers challenged the idea that the identities of the Philadelphians were lost to time. Through the city’s public archives, she discovered that one of the men’s mothers was Native American. His remains must be repatriated through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, the federal law regulating the return of Native American ancestral remains and funerary objects, she said.

“They never did any research themselves on who these people were, they took Morton’s word for it,” Monteiro said. “The people who aren’t even willing to do the research should not be doing this.”

The university removed that cranium from the reburial so it could be assessed for return through NAGPRA. Monteiro and others were further outraged to discover the university had already interred the remains of the other Black Philadelphians just days earlier outside of public view, she said.

Members of the Black Philadelphians Descendant Community Group, which was organized by people including Muhammad who identify as descendants of the individuals in the mausoleum, said in a statement they are “devastated and hurt” that the burial took place without them.

“In light of this new information, they are taking time to process and consider how best to honor their ancestors at a future time,” the group said. Members offered handouts at the February 3 memorial with the new information they had gathered on the individuals in the mausoleum.

“To balance prioritizing the human dignity of the individuals with conservation due diligence and the logistical requirements of Historic Eden Cemetery, laying to rest the 19 Black Philadelphians was scheduled ahead of the interfaith ceremony and blessing,” the Penn Museum said in a statement to The Associated Press.

Woods said he believed most of the community was happy with the decision to reinter the remains at Eden Cemetery, and it was a vocal minority in opposition. He hoped that eventually all the individuals in the mausoleum would be identified and returned.

“We encourage research to be done moving forward,” Woods said, noting the remains of the Black Philadelphians were in the collection for two centuries and, along with his staff, he felt the need to take more immediate action with those remains.

“Let’s not let these individuals sit in the museum storeroom and extend those 200 years anymore,” he said.

Even if all the crania are identified and returned to the community, the university has a long way to go. More than 300 Native American remains in the Morton Cranial Collection still need to be repatriated through Federal law. Woods said the museum recently hired additional staff to expedite that process.