After a student leader of the historic Tiananmen Square protests entered a 2022 congressional race in New York, a Chinese intelligence operative wasted little time enlisting a private investigator to hunt for any mistresses or tax problems that could upend the candidate’s bid, prosecutors say.

“In the end,” the operative ominously told his contact, “violence would be fine too.”

As an Iranian journalist and activist living in exile in the United States aired criticism of Iran’s human rights abuses, Tehran was listening too. Members of an Eastern European organized crime gang scouted her Brooklyn home and plotted to kill her in a murder-for-hire scheme directed from Iran, according to the Justice Department, which foiled the plan and brought criminal charges.

The episodes reflect the extreme measures taken by countries like China and Iran to intimidate, harass and sometimes plot attacks against political opponents and activists who live in the U.S. They show the frightening consequences that geopolitical tensions can have for ordinary citizens as governments historically intolerant of dissent inside their own borders are increasingly keeping a threatening watch on those who speak out thousands of miles away.

“We’re not living in fear, we’re not living in paranoia, but the reality is very clear — that the Islamic Republic wants us dead, and we have to look over our shoulder every day,” the Iranian journalist, Masih Alinejad, said in an interview.

The issue has grabbed the attention of the Justice Department, which in the past five years has charged dozens of suspects with acts of transnational repression. Senior FBI officials said that the tactics have grown more sophisticated, including the hiring of proxies like private investigators and organized crime leaders, and countries are more willing to cross “serious red lines” from harassment into violence as they seek to project power abroad and stifle dissent.

Foreign adversaries are increasingly making well-funded intimidation campaigns a priority for their intelligence services, and more countries — including some not seen as traditionally antagonistic to the U.S. — have targeted critics in America and elsewhere in the West, said the officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss their investigations.

The Justice Department, for instance, announced a disrupted plot last November to kill a Sikh activist in New York that officials said was directed by an Indian government official. Rwanda arrested Paul Rusesabagina of “Hotel Rwanda” fame and returned him to the country before releasing him back to the U.S. last year, and Saudi Arabia has harassed critics online and in person, the FBI has said.

“This is a huge priority for us,” said Assistant Attorney General Matthew Olsen, the Justice Department’s top national security official, describing an “alarming rise” in government-directed harassment.

He said the prosecutions are meant not only to hold harassers accountable but to send a message that the actions are “unacceptable from the perspective of United States sovereignty and defending American values — values around free expression and free association.”

Other nations also have seen a spike in cases.

An April report from Reporters Without Borders called London a “hotspot” for Iranian attacks on Persian-language broadcasters, with British counterterrorism police investigating an attack one month earlier on an Iranian television presenter outside his home in London. In Britain and elsewhere in Europe, harassment and attacks targeting Russians, including a journalist who fell ill from a suspected poisoning in Germany, have long been blamed on Russia’s intelligence operatives despite denials from Moscow.

Inside the U.S., the trend is all the more worrisome because of an ever-deteriorating relationship with Iran and tensions with China over everything from trade and theft of intellectual property to election interference. And emerging technologies like generative AI are likely to be exploited for future harassment, U.S. intelligence officials said in a recent threat assessment.

“Transnational repression is a manifestation of the broader conflict between authoritarian regimes and democratic countries,” Olsen said. “It’s been a consistent theme of the way the world is changing from a geopolitical standpoint over the last decade.”

‘I’M NOT REALLY FEELING SAFE’

Two of the leading culprits, officials and advocates say, are China and Iran. Emails to the Iranian mission at the United Nations were not returned. A spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington disputed that the country engages in the practice, saying in a statement that the government “strictly abides by international law, and fully respects the law enforcement sovereignty of other countries.”

“We resolutely oppose ‘long-arm jurisdiction,'” the statement said.

Yet U.S. officials say China created a program to do exactly that, launching “Operation Fox Hunt” to track down Chinese expatriates wanted by Beijing, with a goal of bullying them into returning to face charges.

A former city government official in China living in New Jersey found a note in Chinese characters taped to his front door that said: “If you are willing to go back to the mainland and spend 10 years in prison your wife and children will be all right. That’s the end of this matter!” according to a 2020 Justice Department case charging a group of Chinese operatives and an American private investigator.

Though most defendants charged in transnational repression plots are based in their home country, making arrests and prosecutions infrequent, that particular case led to convictions last year of the private investigator and two Chinese citizens living in the U.S.

Bob Fu, a Chinese American Christian pastor whose organization, ChinaAid, advocates for religious freedom in China, said he has endured far-ranging harassment campaigns for years. Large crowds of demonstrators have amassed for days at a time outside his west Texas home, arriving in well-coordinated actions he believes can be linked to the Chinese government.

Phony hotel reservations have been made in his name, along with bogus bomb threats to police stating that he planned to detonate explosives. Flyers depicting him as the devil have been distributed to neighbors. He said he’s learned to take precautions when he travels, including asking his staff not to post his itinerary in advance, and relocated from his home at what he said was law enforcement’s urging.

“I’m not really feeling safe,” Fu told AP. When it comes to returning to China, where he was raised and left more than 25 years ago as a religious refugee, he said: “I may be able to travel back, but it’s a one-way ticket. I’m sure I’m on their wanted list.”

Wu Jianmin, a former student leader in China’s 1989 pro-democracy movement, was targeted in 2020 by a group of protesters outside his home in Irvine, California. The harassment lasted more than two months.

“They shouted slogans outside my home and made verbal abuses,” he said. “They paraded in the neighborhood, distributed all sorts of pictures and flyers, and put them in the neighbors’ mailboxes.”

The perpetrators of harassment plots, Wu believes, include retired Communist Party members living in the U.S., their children, members of Chinese associations with close links to the Chinese government and even fugitives seeking bargains with Beijing.

“The end goal is the same,” Wu said in an interview in Mandarin Chinese. “Their task, as assigned by the Communist Party, is to suppress overseas pro-democracy activists.”

Last year, the Justice Department charged about three dozen officers in China’s national police force with using social media to target dissidents inside the U.S., including by creating fake accounts that shared harassing videos and comments, and arrested two men who it says had helped establish a secret police outpost in Manhattan’s Chinatown neighborhood on behalf of the Chinese government.

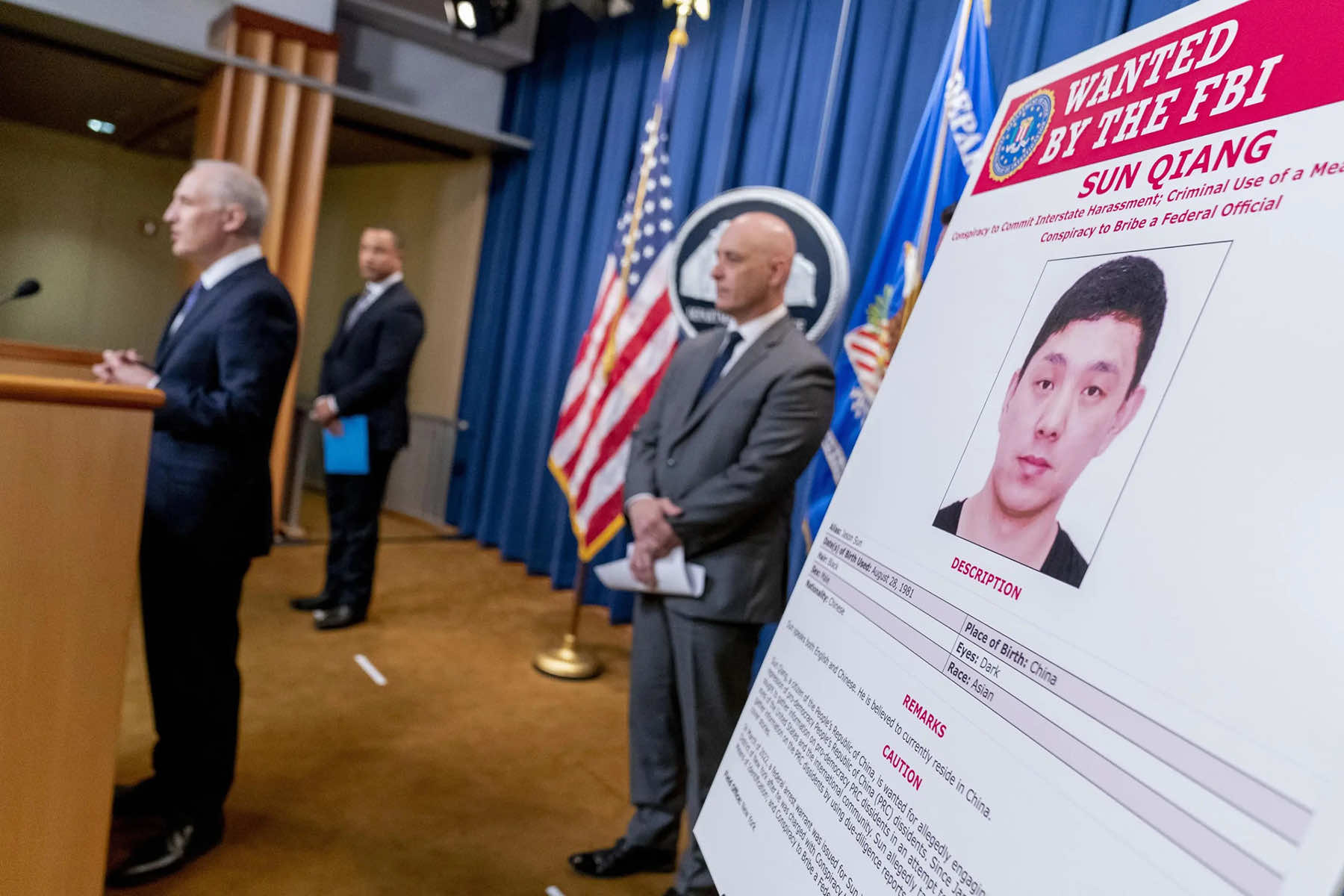

The year before, federal prosecutors in New York disclosed a series of wide-ranging plots to silence dissidents, like the scheme to dig up dirt about the little-known and ultimately unsuccessful congressional candidate.

Other targets have included American figure skater Alysa Liu and her father, Arthur, a political refugee who prosecutors say was surveilled by a man who posed as an Olympics committee member and asked them for their passport information.

A sculpture created by a dissident artist in California that depicted the coronavirus with the face of Chinese President Xi Jinping also was dismantled and burned to the ground.

“We should be under no illusion that somehow these are rogue actors or people that are unaffiliated with the Chinese government,” Representative Raja Krishnamoorthi of Illinois, the top Democrat on a House select committee focused on China, said of the Chinese operatives who have been charged.

‘ERASE HIS HEAD FROM HIS TORSO’

Sometimes violence has been planned in response to world events.

Prosecutors in 2022 charged an Iranian operative with offering $300,000 to “eliminate” Trump administration national security adviser John Bolton as payback for an airstrike that killed Iran’s most powerful general.

A fresh Tehran threat was disclosed this year when the Justice Department charged an Iranian whom officials identified as a drug trafficker and intelligence operative as well as two Canadians — one a “full-patch” member of the Hells Angels motorcycle gang — in a murder-for-hire plot against two Iranians who had fled the country and were living in Maryland.

“We gotta erase his head from his torso,” one of the hired Canadians is accused of saying before the threat was disrupted.

Alinejad, the Iranian journalist, was targeted even before the murder-for-hire plot was announced by the Justice Department last year. Prosecutors in 2021 charged a group of Iranians said to be working at the behest of the country’s intelligence services with planning to kidnap her.

Alinejad remains a prominent journalist and vocal opposition activist and says she’s determined to keep speaking out, including at a sentencing hearing last year for a woman who prosecutors say unwittingly funded the kidnapping plot.

But the details of the plots are chillingly etched in her mind. The criminal cases laid bare the gravity of the threat she faced as well as the intrusive surveillance and the grisly preparations that were involved, including researching how to spirit Alinejad out of New York on a military-style speedboat and discussing lures for getting her from her home — such as asking for flowers from the garden outside.

One of the defendants in the murder-for-hire plot was arrested in 2022 after he was found driving around Alinejad’s Brooklyn neighborhood with a loaded rifle and rounds of ammunition. Another suspect was extradited from the Czech Republic in February to face charges. Two others also have been taken into custody.

The FBI disrupted the plot but also encouraged Alinejad to move, which she has done. But that also meant saying goodbye to her beloved garden, which had brought her joy as she gave homegrown cucumbers and other vegetables to neighbors.

“They didn’t kill me physically, but they killed my relationship with my garden, with my neighbors,” Alinejad said.