A large pool of dark liquid festering on the floor. No fresh air. Computer displays that would overheat and ooze out a fishy-smelling gel that nauseated the crew. Asbestos readings 50 times higher than the Environmental Protection Agency’s safety standards.

These are just some of the past toxic risks that were in the underground capsules and silos where Air Force nuclear missile crews have worked since the 1960s. Now many of those service members have cancer.

The toxic dangers were recorded in hundreds of pages of documents dating back to the 1980s that were obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests. They tell a far different story from what Air Force leadership told the nuclear missile community decades ago, when the first reports of cancer among service members began to surface:

“The workplace is free of health hazards,” a December 30, 2001, Air Force investigation found.

“Sometimes, illnesses tend to occur by chance alone,” a follow-up 2005 Air Force review found. The capsules are again under scrutiny.

In January of 2023 at least nine current or former nuclear missile officers, or missileers, had been diagnosed with the blood cancer non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Then hundreds more came forward self-reporting cancer diagnoses.

In response the Air Force launched its most sweeping review to date and tested thousands of air, water, soil and surface samples in all of the facilities where the service members worked. Four current samples have come back with unsafe levels of polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, a known carcinogen used in electrical wiring.

In early 2024, more data is expected, and the Air Force is working on an official count of how many current or former missile community service members have cancer.

Some current missileers said were concerned by the new reports but believe the Air Force is being transparent in its current search for toxic dangers. Many of them take some of the same precautions missileers have for generations, such as having “capsule clothes,” the civilian attire they change into once inside the capsule to work the 24-hour shift. The clothes go straight into the laundry after a shift because they end up smelling metallic.

“Whenever you hear ‘cancer’ it’s a little concerning,” said Lt. Joy Hawkins, 23, a missileer at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana. To Hawkins and fellow missileer Lt. Samantha McGlinchey, who spoke to reporters as they completed an underground shift at launch control capsule Charlie, the news meant they would need to be diligent about medical checkups. “There’s more testing, things to come, cleanup efforts,” McGlinchey, 28, said. “For us early in our careers, it’s better to be caught so early.”

Others worry the dangers will again be played down. When the latest rounds of test results were released, the Air Force did not initially reveal that samples showing contamination had critically higher PCB levels than EPA standards allow — and dozens of other areas tested were just below the EPA’s threshold, said Steven Mayne, a former senior enlisted nuclear missile facility supervisor at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota who now runs a Facebook group that is dedicated to posting Air Force news or internal memos.

“At this point the EPA, OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) and senators from North Dakota and Montana need to look into this matter,” Mayne said.

In December 2022, former Malmstrom missileers Jackie Perdue and Monte Watts, both of whom have been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, asked the Defense Department’s inspector general to investigate.

“I believe health and safety standards have been violated, or not considered, and should be investigated,” said Perdue, who served as a nuclear missile combat crew commander at Malmstrom from 1999 to 2006.

PAST EXPOSURES

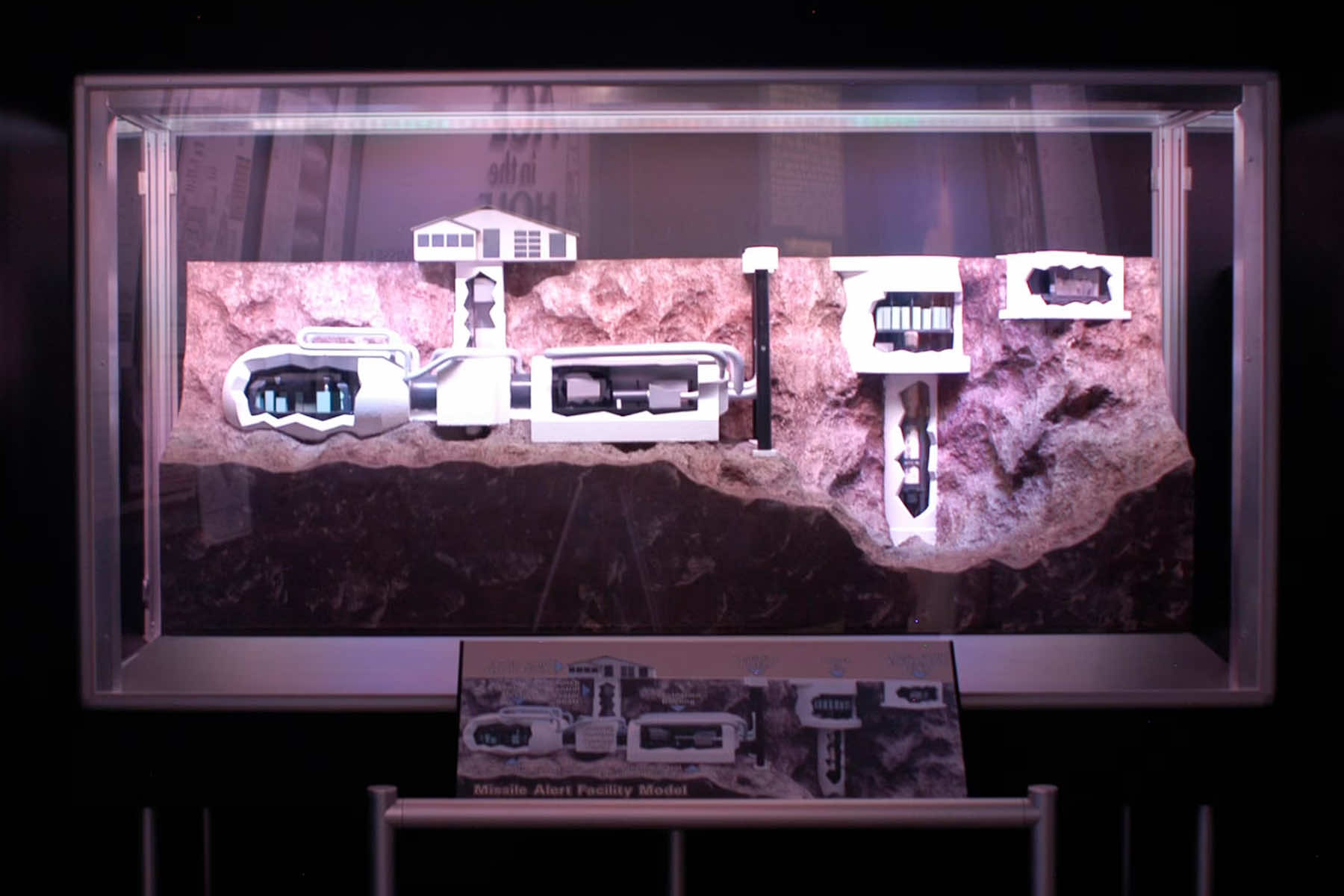

There are currently three nuclear missile bases in the United States: F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming, Minot and Malmstrom. Each base has 15 underground launch control capsules that act as hubs for fields of 10 Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile silos each. The capsules are manned around the clock, 365 days a year. Missileers spend 24 hours or more each shift working underground in those capsules monitoring the ICBMs, ready to launch them if directed by the president.

The Air Force acknowledges the current review cannot provide full answers on what past missileers were exposed to, but the data will establish a health profile likely to help them apply for veterans benefits. However, there are plenty of warning signs about past toxic risks according to documents.

“Type and content of asbestos, please phone ASAP,” a handwritten note read on a memo dated November 9, 1992. All of the documents have been redacted to have the names blocked out, but the urgency was evident. “PRIORITY,” the handwritten note says, in all caps.

An environmental team at Malmstrom capsules Hotel and Juliet got worrisome asbestos readings from underneath a generator in the capsule equipment rooms. The equipment room is also underground, contained within the same, sealed-in workspace. The EPA’s threshold for asbestos exposure is 1% for an eight-hour workday.

But missileers were locked in there for 24 hours at a time, at least. If the weather was bad and the replacement crew couldn’t make the drive to the site, a team could be stuck underground for as long as 72 hours. Hotel and Juliet recorded solid samples of chrysotile asbestos — a white asbestos that can be inhaled — between 15% to 30%.

In the official report published just seven days later, however, the risks were downplayed.

“Asbestos presents a health hazard only when it is crushed (able to be crushed or pulverized by hand pressure.) All suspect (asbestos) was found to be in good condition,” the annual review on Hotel said.

At missile silo Quebec-12 in 1989 it found levels of up to 50% amosite asbestos, a brown asbestos found in cement and insulation. And a team looking at Malmstrom’s Bravo capsule that same year had warned that even if it was left undisturbed, it could be dangerous. “Diesel room — when running leaks asbestos,” it warned.

In his inspector general complaint, former Malmstrom missileer Watts said there was asbestos in the floor tile as well, and that missileers also “routinely removed, handled and replaced these tiles as part of required survival equipment inventories.”

The documents also reveal multiple PCB spills throughout the decades. A 1987 report talks about a missileer calling his commander to report a severe headache and lightheadedness. The crew finds a clear, sticky syrup leaking under the capsule’s power panel.

“I suggested the blast door be opened for more ventilation and no contact with the substance be made,” a bioenvironmental engineer documents. “All the team needed to do was open the blast door and stay away from the spill. There was no need to close the capsule.”

“It’s frustrating to know they had thought of this back then,” said Doreen Jenness, whose husband, Jason Jenness, was a Malmstrom missileer who died of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2001 at the age of 31. “It makes me frustrated and angry that they can keep telling these young men and women that they are not finding anything — knowing that back in 2001, 2003 and the early 2000s that there was something going on there.”

CAPSULE SIERRA

Doreen and Jason Jenness met while he was assigned to Malmstrom. They married and lived on base in the mid-1990s. Their missileer friends used to tease them because they had a golden Labrador named Sierra, the same name as one of the capsules that Jason’s squadron operated.

The environmental reports from Malmstrom when Jason was assigned there show Sierra had a long list of hazards. In 1996, a medical team reported there were more than 25 gallons of fluid overrun with biological growth festering on Sierra’s capsule floor.

An intake that collected outside air for Sierra was located by the parking lot, and the team watched a running car idle near it for 20 minutes. The team documented that a fan needed to pull clean air down into Sierra had been broken for at least six months, so the only way crews could get fresh air was if they left the capsule’s steel vault door open.

At the other capsules, the team said the air quality was “marginal, but should not cause serious health problems.” Sierra was dangerous. In March of 1996, the medical team measured carbon dioxide levels of 1,700 parts per million in the air. “At these levels you can expect complaints of headache, drowsiness, fatigue and/or difficulty concentrating from a majority of the occupants. Worker removal should be considered.”

Nothing changed. That May the medical team again recorded exposure levels of 1,800 ppm, and advised again that the missileers should be removed.

LEAKING COMPUTER CONSOLES

By the mid-1990s a new missile targeting system was needed, and each capsule began a refurbishment to install a wall-sized computer console called REACT, for Rapid Execution and Combat Targeting System.

The new system would allow the U.S. more quickly to reprogram and retarget its nuclear missiles in case of war. Demolition of the old computer and construction of REACT began inside each of the 15 Malmstrom capsules.

Missileers wonder if the REACT refurbishment further disturbed asbestos and PCBs that were still in the capsules. But once installed, the new console also exposed missileers to a new toxic danger.

“Crew members reported a malfunctioning video display characterized by a clicking sound,” a report on a May 1995 incident at Malmstrom’s Bravo capsule said. “After the click, the video display shut down with only a white line visible to crew members.”

A clear liquid began to leak, followed by a fishy, ammonia-like smell. The crew began to complain of headaches and nausea, and the capsule was evacuated two hours later.

Malmstrom’s team learned that the liquid was dimethylformamide, an electrolyte used in REACT’s video display unit capacitors, because F.E. Warren, the Wyoming base, had recently reported similar leaks.

“The capacitors overheat and vent into the capsule in lieu of catastrophic failure,” a 1996 memo found after a second dimethylformamide leak at Bravo. “To date, we have no idea how much of this material is contained in the capsules nor do we have any idea of the relative hazard to missile crews and maintenance personnel who come in contact with this material.”

Medical studies on dimethylformamide’s link to cancer are split; some report a clear tie to liver cancer, others say more study is needed.

CHANGES COMING

All of the capsules will be closed down in a few years, as the military’s new ICBM, the Sentinel, comes online. As part of the modernization, the old capsules will be demolished. A new, modern underground control center will be built on top of them.

Air Force teams working on the new designs are aware of the cancer reports and are applying modern environmental health standards in the new centers — requirements that did not exist when the Minuteman capsules were first built, said Maj. General John Newberry, commander of the Air Force’s nuclear weapons center.

“We are absolutely learning from or understanding what’s going on with Minuteman III, and if there’s something that we need to look at from a Sentinel side,” Newberry said.

The old capsules will remain in use until then, though, which makes it even more important that the Air Force is completely open with its missileers now, Doreen Jenness said.

Because they were so young, neither she nor Jason suspected cancer when he started to feel fatigued in the fall of 2000. Nor when his hip started to ache that December.

When he finally gave in and saw a doctor in February 2001, he was admitted to the hospital the same day. By March, Jason and Doreen knew his lymphoma was untreatable. He died that July.

“We can all pretend to not know, because knowing is really hard,” Doreen Jenness said. “Knowing and doing something about it is even harder. Now, 23 years after Jason’s been gone there’s a whole bunch of young men and women that are having to go through the same things that we had to go through. They have to live the same lives and maybe have the same future as me, and it’s just sad. Really sad.”