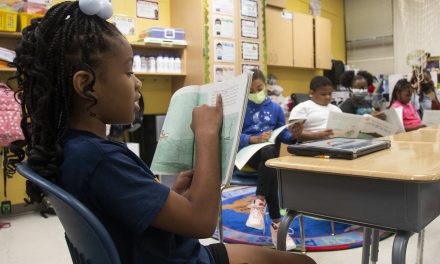

Mary Louis’ excitement to move into an apartment in Massachusetts in the spring of 2021 turned to dismay when Louis, a Black woman, received an email saying that a “third-party service” had denied her tenancy.

That third-party service included an algorithm designed to score rental applicants, which became the subject of a class action lawsuit, with Louis at the helm, alleging that the algorithm discriminated on the basis of race and income.

A federal judge approved a settlement in the lawsuit, one of the first of it is kind, with the company behind the algorithm agreeing to pay over $2.2 million and roll back certain parts of it is screening products that the lawsuit alleged were discriminatory.

The settlement does not include any admissions of fault by the company SafeRent Solutions, which said in a statement that while it “continues to believe the SRS Scores comply with all applicable laws, litigation is time-consuming and expensive.”

While such lawsuits might be relatively new, the use of algorithms or artificial intelligence programs to screen or score Americans is not. For years, AI has been furtively helping make consequential decisions for U.S. residents.

When a person submits a job application, applies for a home loan or even seeks certain medical care, there is a chance that an AI system or algorithm is scoring or assessing them like it did Louis. Those AI systems, however, are largely unregulated, even though some have been found to discriminate.

“Management companies and landlords need to know that they’re now on notice, that these systems that they are assuming are reliable and good are going to be challenged,” said Todd Kaplan, one of Louis’ attorneys.

The lawsuit alleged SafeRent’s algorithm did not take into account the benefits of housing vouchers, which they said was an important detail for a renter’s ability to pay the monthly bill, and it therefore discriminated against low-income applicants who qualified for the aid.

The suit also accused SafeRent’s algorithm of relying too much on credit information. They argued that it fails to give a full picture of an applicant’s ability to pay rent on time and unfairly dings applicants with housing vouchers who are Black and Hispanic partly because they have lower median credit scores, attributable to historical inequities.

Christine Webber, one of the plaintiff’s attorneys, said that just because an algorithm or AI is not programmed to discriminate, the data an algorithm uses or weights could have “the same effect as if you told it to discriminate intentionally.”

When Louis’ application was denied, she tried appealing the decision, sending two landlords’ references to show she had paid rent early or on time for 16 years, even if she did not have a strong credit history.

Louis, who had a housing voucher, was scrambling, having already given notice to her previous landlord that she was moving out, and she was charged with taking care of her granddaughter.

The response from the management company, which used SafeRent’s screening service, read, “We do not accept appeals and cannot override the outcome of the Tenant Screening.”

Louis felt defeated. The algorithm did not know her, she said.

“Everything is based on numbers. You don’t get the individual empathy from them,” said Louis. “There is no beating the system. The system is always going to beat us.”

While state lawmakers have proposed aggressive regulations for these types of AI systems, the proposals have largely failed to get enough support. That means lawsuits like Louis’ are starting to lay the groundwork for AI accountability.

SafeRent’s defense attorneys argued in a motion to dismiss that the company should not be held liable for discrimination because SafeRent wasn’t making the final decision on whether to accept or deny a tenant. The service would screen applicants, score them and submit a report, but leave it to landlords or management companies to accept or deny a tenant.

Louis’ attorneys, along with the U.S. Department of Justice, which submitted a statement of interest in the case, argued that SafeRent’s algorithm could be held accountable because it still plays a role in access to housing. The judge denied SafeRent’s motion to dismiss on those counts.

The settlement stipulates that SafeRent cannot include its score feature on its tenant screening reports in certain cases, including if the applicant is using a housing voucher. It also requires that if SafeRent develops another screening score it plans to use, it must be validated by a third-party that the plaintiffs agree to.

Louis’ son found an affordable apartment for her on Facebook Marketplace that she has since moved into, though it was $200 more expensive and in a less desirable area.

“I’m not optimistic that I’m going to catch a break, but I have to keep on keeping, that’s it,” said Louis. “I have too many people who rely on me.”