The struggle between the Trump-backed forces of authoritarianism and those of us defending democracy is coming down to the fight over whether the Democrats can get the Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Act through the Senate.

It is worth reading what is actually in the bills because, to my mind, it is bananas that they are in any way controversial.

The Freedom to Vote Act is a trimmed version of the For the People Act the House passed at the beginning of this congressional session. It establishes a baseline for access to the ballot across all states. That baseline includes at least two weeks of early voting for any town of more than 3000 people, including on nights and weekends, for at least 10 hours a day. It permits people to vote by mail, or to drop their ballots into either a polling place or a drop box, and guarantees those votes will be counted so long as they are postmarked on or before Election Day and arrive at the polling place within a week. It makes Election Day a holiday. It provides uniform standards for voter IDs in states that require them.

The Freedom to Vote Act cracks down on voter suppression. It makes it a federal crime to lie to voters in order to deter them from voting (distributing official-looking flyers with the wrong dates for an election or locations of a polling place, for example), and it increases the penalties for voter intimidation. It restores federal voting rights for people who have served time in jail, creating a uniform system out of the current patchwork one.

It requires states to guarantee that no one has to wait more than 30 minutes to vote.

Using measures already in place in a number of states, the Freedom to Vote Act provides uniform voter registration rules. It establishes automatic voter registration at state Departments of Motor Vehicles, permits same-day voter registration, allows online voter registration, and protects voters from the purges that have plagued voting registrations for decades now, requiring that voters be notified if they are dropped from the rolls and given information on how to get back on them.

The Freedom to Vote Act bans partisan gerrymandering.

The Freedom to Vote Act requires any entity that spends more than $10,000 in an election to disclose all its major donors, thus cleaning up dark money in politics. It requires all advertisements to identify who is paying for them. It makes it harder for political action committees (PACs) to coordinate with candidates, and it beefs up the power of the Federal Election Commission that ensures candidates run their campaigns legally.

The Freedom to Vote Act also addresses the laws Republican-dominated states have passed in the last year to guarantee that Republicans win future elections. It protects local election officers from intimidation and firing for partisan purposes. It expands penalties for tampering with ballots after an election (as happened in Maricopa County, Arizona, where the Cyber Ninjas investigating the results did not use standard protection for them and have been unable to produce documents for a freedom of information lawsuit, leading to fines of $50,000 a day and the company’s dissolution). If someone does tamper with the results or refuses to certify them, voters can sue.

The act also prevents attempts to overturn elections by requiring audits after elections, making sure those audits have clearly defined rules and procedures. And it prohibits voting machines that don’t leave a paper record.

The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act (VRAA) takes on issues of discrimination in voting by updating and restoring the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA) that the Supreme Court gutted in 2013 and 2021. The VRA required that states with a history of discrimination in voting get the Department of Justice to approve any changes they wanted to make in their voting laws before they went into effect, and in the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision, the Supreme Court struck that requirement down, in part because the justices felt the formula in the law was outdated.

The VRAA provides a new, modern formula for determining which states need preapproval, based on how many voting rights violations they’ve had in the past 25 years. After ten years without violations, they will no longer need preclearance. It also establishes some practices that must always be cleared, such as getting rid of ballots printed in different languages (as required in the U.S. since 1975).

The VRAA also restores the ability of voters to sue if their rights are violated, something the 2021 Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee decision makes difficult. The VRAA directly addresses the ability of Indigenous Americans, who face unique voting problems, to vote. It requires at least one polling place on tribal lands, for example, and requires states to accept tribal or federal IDs.

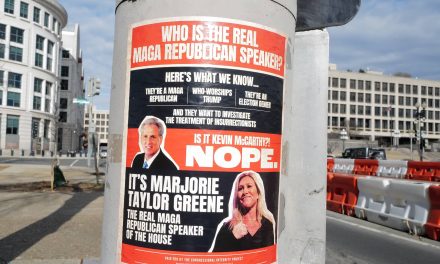

That is it. It is off-the-charts astonishing that no Republicans are willing to entertain these common-sense measures, especially since there are in the Senate a number of Republicans who voted in 2006 to reauthorize the 1965 Voting Rights Act the VRAA is designed to restore.

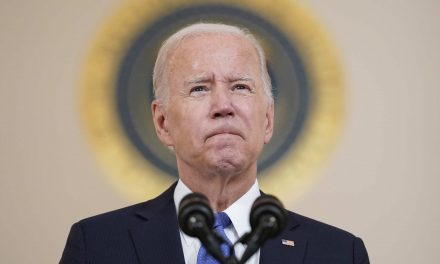

McConnell revealed on January 12 his discomfort with President Joe Biden’s January 11 speech at the Atlanta University Center Consortium, when Biden pointed out that “[h]istory has never been kind to those who have sided with voter suppression over voters’ rights. And it will be even less kind for those who side with election subversion.” Biden asked Republican senators to choose between our history’s advocates of voting rights and those who opposed such rights. He asked: “Do you want to be … on the side of Dr. King or George Wallace? Do you want to be on the side of John Lewis or Bull Connor? Do you want to be on the side of Abraham Lincoln or Jefferson Davis?

McConnell, who never complained about the intemperate speeches of former president Donald Trump, said Biden’s speech revealed him to be “profoundly, profoundly unpresidential.”

The voting rights measures appear to have the support of the Senate Democrats, but because of the Senate filibuster, which makes it possible for senators to block any measure unless a supermajority of 60 senators are willing to vote for it, voting rights cannot pass unless Democrats are willing to figure out a way to bypass the filibuster. Two Democratic senators, Krysten Sinema (D-AZ) and Joe Manchin (D-WV), are currently unwilling to do that.

Nine Democratic senators eager to pass this measure met with Sinema and Manchin an attempt to get them to a place where they are willing to change the rules of the Senate filibuster to protect our right to vote. They have not yet found a solution.

Senate Majority Leader Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) announced on January 12 that he would bring voting rights legislation to the Senate floor for debate — which Republicans have rejected — by avoiding a Republican filibuster through a complicated workaround. When the House and Senate disagree on a bill (which is almost always), they send it back and forth with revisions until they reach a final version.

According to Democracy Docket, after it has gone back and forth three times, a motion to proceed on it cannot be filibustered. So, Democrats in the House are going to take a bill that has already hit the three-trip mark and substitute for that bill the Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. They will pass the combined bill and send it to the Senate, where debate over it cannot be filibustered.

And so, Republican senators will have to explain to the people why they oppose what appear to be common-sense voting rules.

Jоеy Csυnyо

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics