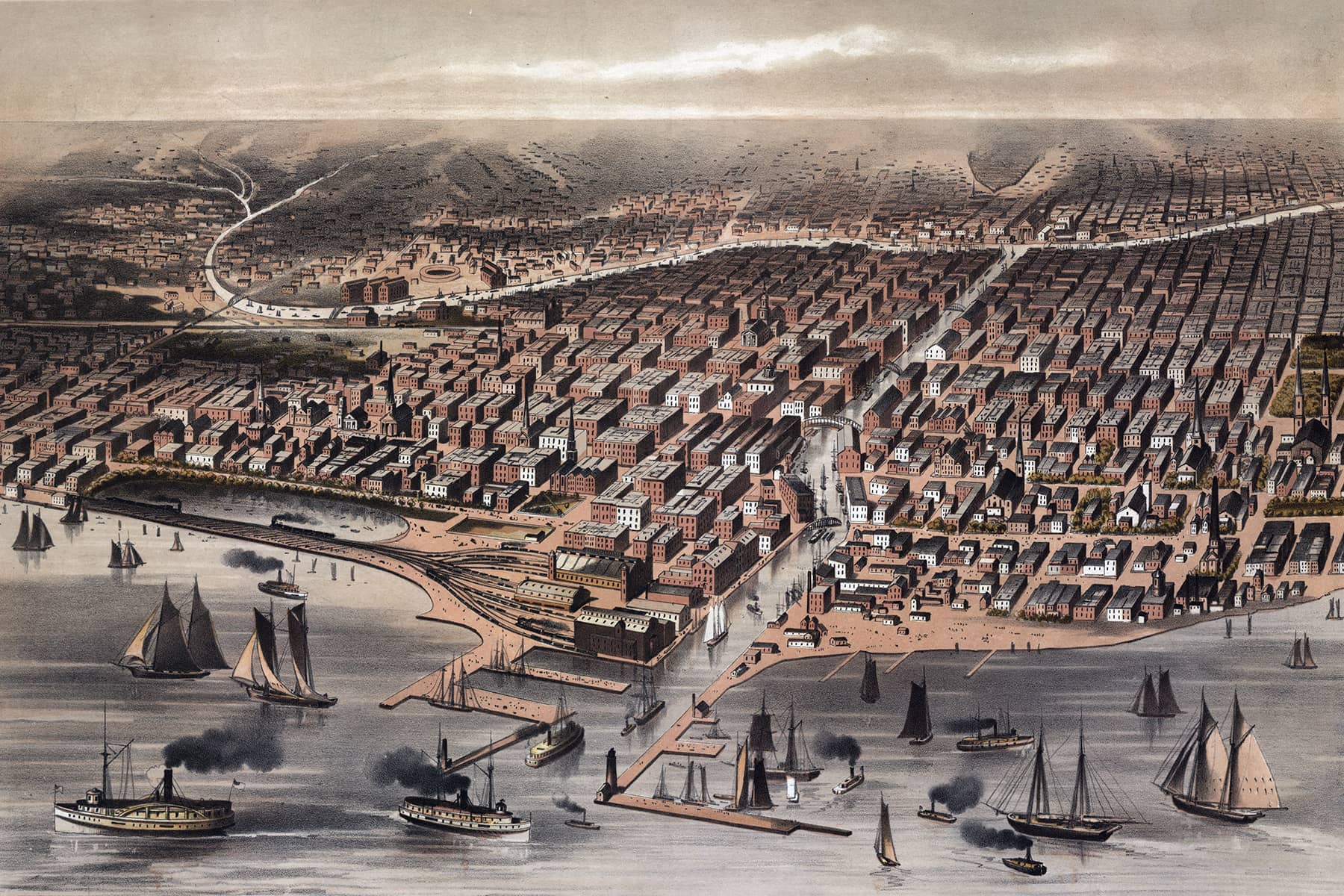

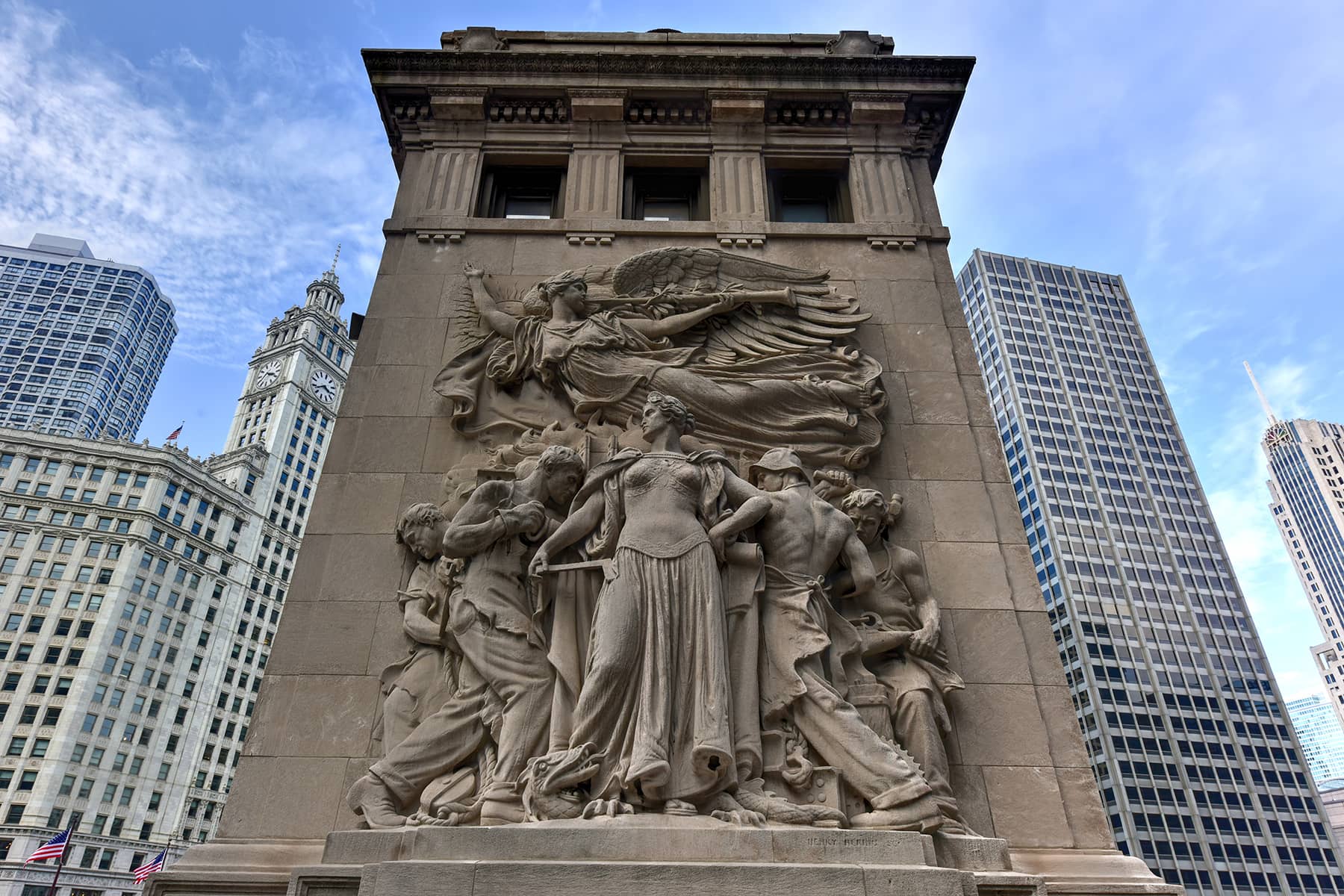

On October 8, 1871, dry conditions and strong winds drove deadly fires through the Midwest. The Peshtigo Fire in northeastern Wisconsin and parts of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula burned more than 1.2 million acres and 17 towns, claiming between 1,500 and 2,500 lives. The Great Chicago Fire burned 3.3 square miles of the city, destroying the wooden structures that made up the relatively new town, killed about 300 people, and left more than 100,000 people homeless.

The Peshtigo Fire is the deadliest wildfire in U.S. history. The Chicago Fire is the one people remember.

The difference is in part because Chicago was a city, of course, easy for newspapers to cover, while the Pestigo fire killed people in lumber camps and small towns. But the Great Chicago Fire also told a political story that fit into an emerging narrative about the danger of organized labor.

It was not clear, coming out of the Civil War, how Republicans would stand with regard to workers. After all, the U.S. government had fought the war to protect the right of every man to enjoy the fruits of his own labor. But immediately after the war, workers had started organizing to demand adjustments to the wartime financial policies that favored men with money. By 1866 the Democratic Party had begun to listen to them, and leaders called for rewriting the terms of the Civil War debt, which had been generous to investors in the days when they were a risky investment. After the war, with the U.S. secure, the calculations changed, and Democrats charged that investors had gotten too good a deal.

Republicans were horrified at the idea of changing the terms of a debt already incurred, and added to the Fourteenth Amendment the clause saying, “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned.”

They were also concerned when more than 60,000 people came together in August 1866 to launch the National Labor Union, calling for the government to level the playing field between workers and their employers. They asked for an eight-hour day, an end to monopolies, and cooperation between Black and white workers. In 1867, in what was almost certainly a misquoted comment, stories spread that Republican lawmaker Benjamin Franklin Wade of Ohio had told an audience in Kansas that “property is not equally divided, and a more equal distribution of capital must be wrought out.”

Also in 1867, Congress passed the Military Reconstruction Act, which divided the ten unreconstructed states into five military districts and required new state constitutional conventions to rewrite the state constitutions. For the first time in history, the new law permitted Black men to vote for delegates to those conventions.

When former Confederates preferred to live under military rule rather than share political power with their Black neighbors, Congress amended the Military Reconstruction Act to permit the military to enroll voters. In 1868, Congress passed and then states ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, protecting the right of all citizens to the due process of the laws. In 1870, Congress passed and the states ratified the Fifteenth Amendment, protecting Black male voting. And then, when white reactionaries organized as the Ku Klux Klan to keep Black men and white Republicans from voting for the constitutions the conventions had written, Congress created the Department of Justice to prosecute Ku Klux Klan members and protect Black rights in the South.

Attacks on Black political rights on grounds of race were now unconstitutional, and the federal government seemed prepared to back that principle up with the law. So reactionary southerners took a new tack.

Beginning in 1871, they argued that they had no objection to their Black neighbors on racial grounds. What they objected to, they said, was that these folks, newly out of enslavement, were poor. White leaders claimed that the South remained in a recession not because India and Egypt had taken over the cotton market during the war, but because Black southerners were lazy and hoped to use their new political power to redistribute the wealth of white landowners into their own pockets.

When South Carolina voters put into office a majority-Black legislature, white South Carolinians railed against the Black voters “plundering” taxpayers. One observer commented that “a proletariat Parliament has been constituted, the like of which could not be produced under the widest suffrage in any part of the world save in some of these Southern States.” Democrats organized a “Tax-Payers’ Convention” to protest new taxes levied by the legislature.

While Republicans were unwilling to bow to the Ku Klux Klan’s violence against their Black colleagues on racial grounds, this attack had legs, thanks, in part, to events in Europe.

For two months in spring 1871, in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, workers took over the city of Paris and established the Paris Commune. American newspapers plastered details of the Commune on their front pages, describing it as a propertied American’s worst nightmare. They highlighted the murder of priests, the burning of the Tuileries Palace, and the bombing of buildings by women who lobbed burning bottles of newfangled petroleum through cellar windows. American newspapers portrayed the Communards as a “wild, reckless, irresponsible, murderous mobocracy” who brought to life a chaotic world in which workers had taken over the government with a plan to confiscate all property and transfer all money, factories, and land to workers.

Republicans’ fear of workers grew. Organized laborers “are agrarians, levelers, revolutionists, inciters of anarchy, and, in fact, promoters of indiscriminate pillage and murder,” the Boston Evening Transcript charged. The Philadelphia Inquirer insisted the redistribution of wealth through law appealed to poor, lazy, vicious men who would rather steal from the nation’s small farmers and mechanics than work themselves. Scribner’s Monthly warned in italics: “the interference of ignorant labor with politics is dangerous to society.”

Turning first against Black southerners, Republican newspapers began to claim that African Americans were radical levelers. They were “ignorant, superstitious, semi-barbarians” who were “extremely indolent, and will make no exertion beyond what is necessary to obtain food enough to satisfy their hunger.” To these lazy louts, Republicans had given the vote, which gave them “absolute political supremacy.” They elected to office leaders who promised to confiscate wealth through taxation and give it to Black citizens in the form of roads, schools, and hospitals. “The most intelligent, the influential, the educated, the really useful men of the South, deprived of all political power,” wrote the New York Daily Tribune, “[are] taxed and swindled by a horde of rascally foreign adventurers, and by the ignorant class, which only yesterday hoed the fields and served in the kitchen.”

After the Paris Commune, Republicans began to sweep white workers into this equation as well, taking the lead of former Confederates. An article in the New York Daily Tribune quoted Georgia Democrat Robert Toombs, the first Confederate secretary of state, who explicitly compared formerly enslaved people to the Paris Communards. He called for a property requirement for voting, without which “the lower classes…the dangerous, irresponsible element,” would control government and “attack the interests of the landed proprietors.” According to Toombs: “Only those who owned the country should govern it, and men who had no property had no right to make laws for property-holders.”

When Chicago went up in flames in October 1871, some Americans blamed the Great Fire on “communists” eager to take over the country. Even those unconvinced a deadly fire in a wooden city was part of a deliberate plot blamed the fire on stupid immigrant workers careless about fire. They blamed “Mrs. O’Leary and her cow,” claiming the animal had kicked over a lantern near straw, and even children knew not to put fire near straw.

The Great Chicago Fire spoke to politics as the rural Peshtigo Fire did not. It fanned the flames of fear that workers were trying to destroy America and must be cut out of the body politic. Famous reformer Charles Loring Brace wrote, “In the judgment of one who has been familiar with our ‘dangerous classes’ for twenty years, there are just the same explosive social elements beneath the surface of New York as of Paris.”

And the Great Chicago Fire was an illustration of precisely that.

Fеlіx Lіpоv and the Library of Congress

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics