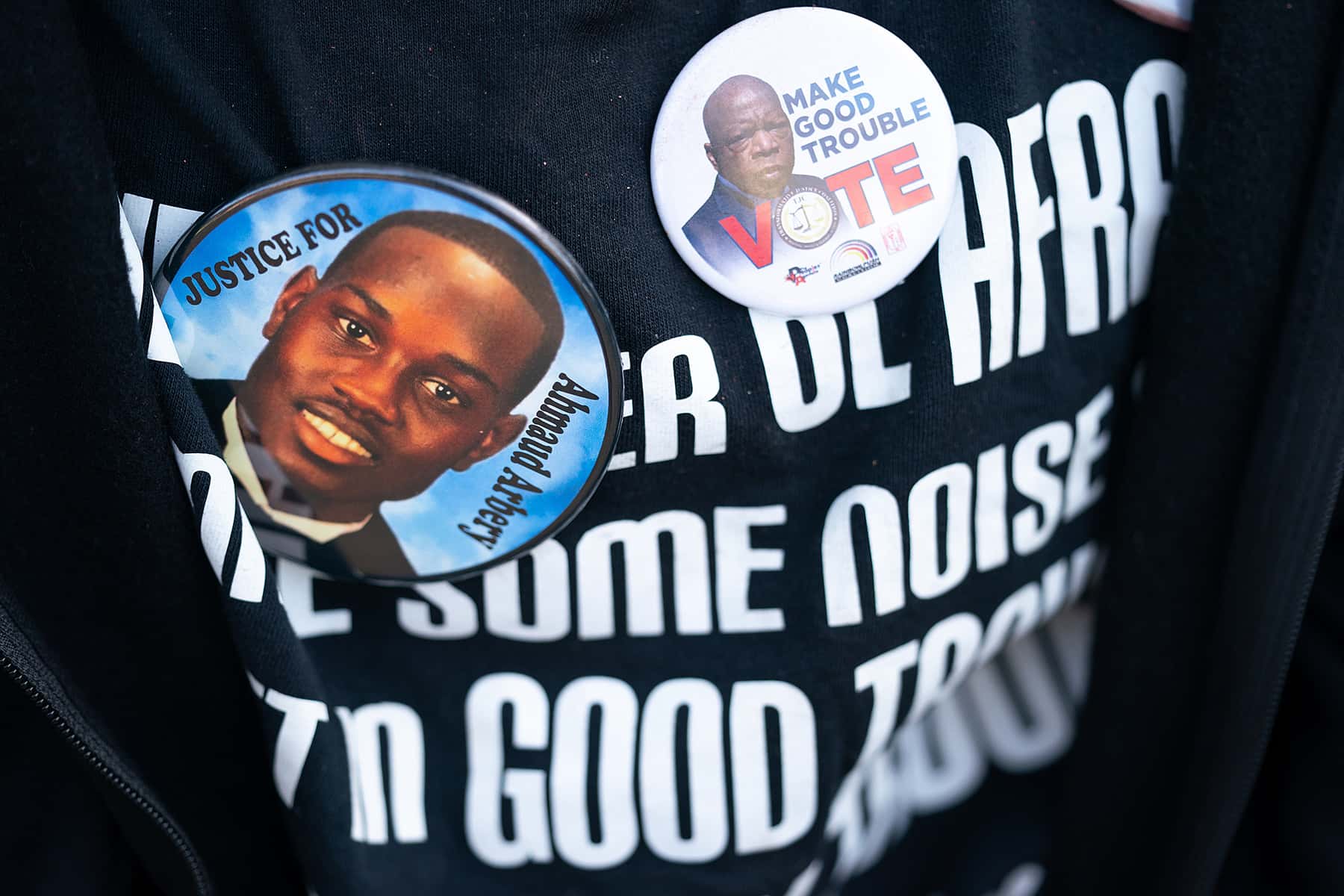

On November 24, just before the Thanksgiving holiday, a jury found Gregory McMichael (65), his son Travis McMichael (35), and their neighbor William “Roddie” Bryan (52) guilty on 23 counts in the murder of Ahmaud Arbery on February 23, 2020, near Brunswick, in Glynn County, Georgia.

Ahmaud Marquez Arbery (25), was a former high school football player who ran every day. On February 23, he was running through a primarily white neighborhood about two miles from his mother’s house when the McMichaels saw him go by. Gregory McMichael had retired from the Glynn County police force and had been an investigator for the Brunswick District Attorney’s office. He picked up a .357 Magnum revolver, Travis grabbed a shotgun, and they hopped into a pickup truck and followed Arbery. Bryan followed the McMichaels and recorded what happened next on his cellphone.

The video shows Arbery jogging toward a white truck with Gregory McMichael standing in the truck bed on a quiet, flat, somewhat rural looking street. Arbery moves to go to the right of the truck, and when he reaches the front, just out of sight, a shot fires. Arbery comes back into view on the left side of the truck and moves toward the left side of the road, where he begins to struggle with Travis McMichael, who is holding a shotgun. Two more shots and Arbery staggers to the middle of the road in front of the truck before falling forward.

Police responded to the scene after a call saying there were “shots fired and a male on the ground ‘bleeding out.’” Mr. Arbery died at 1:08.

Law enforcement officers arrived minutes later and found the McMichaels standing over Arbery’s body. Bryan was in his vehicle. The officers took the McMichaels in for questioning and called the office of the Brunswick district attorney, Jackie Johnson, to ask for legal advice. Assistants there told the officers that the McMichaels should not be arrested.

The police report of the incident, taken largely from an account by Gregory McMichael, said that Arbery had “violently attack[ed]” Travis McMichael and had been shot when the two men fought over a shotgun.

The assistants in Johnson’s office had also told the police officers that the office had a conflict of interest in the case and would need to bring in another prosecutor. Before he retired in 2019, Gregory McMichael had worked as an investigator in her office for more than 30 years. Phone records show he called Johnson shortly after the shooting.

When she heard of what had happened, Johnson immediately contacted George E. Barnhill, the district attorney for Georgia’s Waycross Judicial Circuit. Barnhill watched Bryan’s video and, the next morning, told Glynn County police that Georgia’s citizens arrest law enabled the men to chase Arbery and that they had shot him in self-defense. Glynn County commissioners blame Barnhill’s early advice to the police for delaying the case.

On February 27, Johnson officially recused herself from the case, and the next day, Georgia Attorney General Christopher M. Carr appointed Barnhill to prosecute the case. Carr did not know Barnhill had already reviewed evidence.

Arbery’s family protested Barnhill’s appointment, since Barnhill’s son works as an assistant district attorney in Johnson’s office.

By April 2, Barnhill acknowledged he had a conflict of interest in the case, and yet on April 3 he issued a letter to the Captain of the Glynn County Police Department saying that the McMichaels were within their rights to chase Arbery under Georgia’s law permitting citizen’s arrests, that they were legally allowed to carry guns, and that Travis McDaniel had fired the shotgun out of self defense. “We do not see grounds for an arrest of any of the three parties,” he wrote.

Barnhill officially recused himself on April 7. Carr said he should never have agreed to prosecute the case in the first place, and he began an investigation into Johnson, who had recommended Barnhill without disclosing that she had already had him talk to police about the case.

On April 13, Carr appointed Tom Durden, the district attorney for Liberty County, one county over from the Brunswick Judicial Circuit, to prosecute the case. “We don’t know anything about the case,” Durden told reporters. “We don’t have any preconceived idea about it.”

And there, things might have rested, much as they have so often rested in our nation’s long history when white men have killed Black men.

But in the weeks since the shooting, the community had become increasingly insistent on hearing answers. A local journalist for the daily Brunswick News named Larry Hobbs noted right away that police were not forthcoming about what had happened. He stayed on the story.

Arbery’s family and friends kept up pressure on the Glynn police department, which was already under investigation for corruption on a different matter, and on the prosecutors. Their outrage went national on April 26, when the New York Times reported on the murder, noting that there had been no arrests.

Finally, on May 5, the case broke open. Apparently thinking that since Barnhill had found Bryan’s video exonerating, everyone else would, too, Gregory McMichael worked with lawyer Alan Tucker to take the video to a local radio station, which uploaded it for public viewing.

The station took it down two hours later, but not before a public outcry. Carr promptly asked the Georgia Bureau of Investigation to take over the case. Two days later, on May 7, 74 days after Arbery was killed, GBI officers arrested the McMichaels.

On May 11, the case was reassigned to Joyette M. Holmes at the Cobb County District Attorney’s office and transferred to Atlanta, about 270 miles away from Brunswick.

On May 21, 2020, Bryan was arrested.

And on November 24, after a 13-day trial, a jury with only one Black person found Gregory McMichael, Travis McMichael, and William “Roddie” Bryan guilty of malice murder, felony murder, aggravated assault, false imprisonment and criminal attempt to commit a felony. In February, they will face federal charges of committing hate crimes.

Also on Wednesday, Johnson turned herself in to officials after a grand jury indicted her for violating her oath of office and obstructing police, saying she used her position to discourage law enforcement officers from arresting the McMichaels.

Today, Cobb District Attorney Flynn D. Broady Jr. issued a statement claiming that the jury’s verdict “reflects a new direction for our communities, this State, and the nation, to denounce hate, division and intolerance and promote unity.” We must never forget our past, he said, but instead “understand our prior shortcomings and work to the goal enumerated in our founding documents, ‘all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’ and may we add Justice. In order to do that it takes strength and courage, to demand the rights entitled to us by our Constitution and laws.”

Broady called out Arbery’s mother, Wanda Cooper Jones, and his father, Marcus Arbery, for their courage in insisting on justice for their son, and claimed “the citizens of this state and this nation stood with Wanda and Marcus and their family.”

That local Georgians refused to let Arbery’s case go, and that the Georgia Bureau of Investigation brought charges immediately as soon as they were brought into the case, and that an overwhelmingly white jury found the three men guilty all lend credence to Broady’s statement.

But there is one sticking point: if Gregory McMichael had not produced that video, it’s entirely possible that the crime and its coverup would never have been prosecuted.

Sеаn Rаyfоrd and Stеphеn B. Mоrtоn

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics