“What White people have to do is try to find out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a nigger in the first place. Cause I’m not a nigger, I’m a man. But if you think I’m a nigger it means you need him. The question you gotta ask yourself, the White population of this country has got to ask itself, if I’m not the nigger here and you invented him – you, the white people, invented him – then you have to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that.”

– James Baldwin, 1963 Interview

The night of Thursday, October 11, 2018, Shorewood High School’s theater was empty. No actors took the stage, no lines were read, and no seat was taken to see the Drama Department’s production of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. Earlier that day, the play was canceled amidst concern over its use of the word “nigger.”

In the year 2018, the themes of the play, sadly, are as relevant as they were in the 1930s. A Black man accused of a crime he didn’t commit, a community silently complicit, an unjust judicial system, racism, privilege and fragility. These are the themes we see unfold in the small-town America of Harper Lee’s story.

The word “nigger” is written on the pages of Lee’s novel 44 times. There are fewer occurrences in the stage production, but its sting is still felt every day by African Americans like me whose lives are impacted by it. Whether or not the show goes on, the real-life implications of the attitudes the play portrays go on for people of color in our country. Many in our community felt compelled to shield students and their families from the pain and discomfort of hearing the word. Heard once or heard 44 times – that pain is real.

If your eyes are open and your heart ready, it is easy to feel the cruel parallels between the fate of the fictional character of Tom Robinson, shot 17 times, and that of Milton Hall, shot 11 times, Dontre Hamilton, 14 times, and Trayvon Martin, killed with a single shot. The similarities between the fictional story of Harper Lee’s Robinson family and the lived experience of many Black Americans played a significant role in why the stage fell silent in Shorewood.

Six Letters of Fiction

The idea of the “nigger” is not the derogatory birthright of Black Americans. It is a work of fiction hundreds of years in the making and imposed on millions to stave off the ever-present, yet elusive truth that all humans are created equal. The energy required to uphold that illusion steadily erodes the wellbeing and future of our entire nation.

The word is the offspring of White America and to frame it otherwise would be misleading and disingenuous. Those shielded from hearing it are also those who need to know the meaning of the word the most. Because the word is not the legacy of African-Americans, but rather a yet-to-be resolved legacy of trauma for the White Americans who created it.

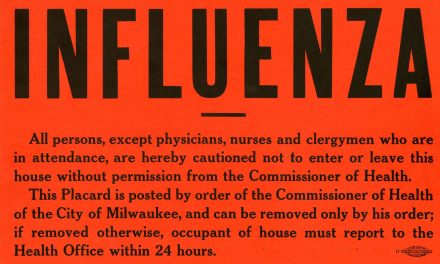

The word was the last one heard by countless men and women before they were murdered. The word was in the room as bombs were built that killed four little black girls, and the word is imbedded within the increasing, intentional racial polarization of our country. As you hear that one word, know what it represents and where it came from.

Yet, the pain White America may feel when hearing the word signals their opportunity for healing to occur. The pain of hearing the word may weaken their grasp on the entitled and magical thinking that if they choose to not say the word, or even hear it, no damage will be done. But each day damage is done even when the word is no longer heard. Its legacy and lifeblood are firmly nestled, untouched, in the hearts of millions who never dare to utter it.

By facing the word, we are able to counter it with words of understanding and hope, with conversations leading to healing and forgiveness. Underused words that have the power to help Americans finally acknowledge their role in the legacy of racism and how they must do more. Compel them to do more than put up progressive yard signs or vote liberal in each election cycle, but to actually step aside, listen and allow themselves to be transformed. Not take the lead like Atticus Finch, but listen as a peer, a brother, a sister, a friend. Listen and look within to question the lives they’ve lead. Examine the homogeneity of their world, their silence when words of hate are spoken at work or around the Thanksgiving table, or their own occasional dance to the rhythm that keeps the beat of the word alive.

Be Better Than Atticus

Americans have long identified with the fictionalized paragon of virtue that is Atticus Finch. But it is clear that as a country we have fallen short of the most basic attributes of Atticus’ character. Had we lived up to the idealized image of Atticus Finch, we would not have real-life Tom Robinsons in the form of Trayvon, Milton or Dontre dotting our landscape. If we were Atticus, Milwaukee would not be the most segregated city in the nation. And if we were Atticus, we would not continue to look the other way as words of genocide, hate and discrimination become the new normal in increasingly abnormal times. Atticus was not enough to alter the outcome of Tom Robinson’s story and therefore we must do better.

Once the curtain falls on the production of To Kill A Mockingbird, whether in Shorewood, Wisconsin or on any stage in America, the long-running show of injustice, discrimination and complicity will go on until people decide to pierce the silence with words of courage, resilience and change.

Let Our Scouts Lead the Way

But hope lies in the hearts of the young. Those who are striving to understand the world they live in, knowing that it is theirs to shape. Whether naive or courageous, that genuine desire to understand was in Scout’s heart as she asked her father, “Do you defend niggers?” The word uttered, the difficult conversation had, and ideally an opportunity for change that is seized.

A child asks about a word and through that we realize that the word, its history and its origin can only be understood if spoken. If we remain silent, the hatred behind it goes unchallenged, an opportunity for change is lost and the silence of a community continues.

Silence is acceptance and avoiding the discussion is complicity.

One day soon, the curtain will rise and a diverse cast of students will play their parts as actors, but more importantly as those courageous enough to know that their words will pierce the silence.

When they take the stage, it is imperative that we open our hearts and listen. We are not Atticus and the towns in which we live must be better than Maycomb, Alabama. We must listen, learn and allow ourselves to follow the students’ lead.

This is a shared moral imperative and the future of our country depends on it.

© Photo

Lee Matz and Universal Pictures