It’s so easy to visit another city and simultaneously fall in love with it while bemoaning the apparent shortcomings of one’s home city. I went to Paris, fell in love, and suddenly, in my mind, Milwaukee seemed to lack vibrant public places where the multitudes, both residents and tourists, would gather morning, noon and night. Where was the Jardin de Luxembourg where Milwaukeeans could picnic and nap, drink wine and canoodle, smoke and strum guitars? I visited NYC, came home, and Milwaukee didn’t have enough public benches or places to play chess in the parks. I traveled to Denver and bemoaned our lack of a vibrant mural culture which, of course, is now rapidly changing here in Milwaukee. And then there are the silly, obvious things that can’t be helped: I went to San Francisco – no hills in Milwaukee. Dominical – no ocean. Key West – no snorkeling. Colorado – no mountains. And so on.

This month, my husband and I visited Portland together for the first time then revisited the city I grew up in, Seattle. A vacation had been long overdue, and we were excited to explore some new and familiar territory together – and to enjoy unusually clear skies and temperatures in the 80s and 90s for a week. We logged tens of thousands of steps each day, walking, hiking and biking our way through two beautiful cities that also happen to be, I learned, two of the whitest big cities in the country. More on that later.

As my husband will tell it, within five minutes of being in the City of Roses, I wanted to move there. It is true that only a few blocks into our two-hour bike tour on the north side, I was remarking jokingly every few blocks that I was going to start a Portland job search or was going to research available homes. I had prepared for Portland’s supposed “weirdness” by watching the first season of Portlandia, with its send-ups of the city’s culture and ideals. It seemed pretty normal, though, whatever that means. What it turned out to be was pretty white, as Portlandia’s cast of characters serves to emphasize. Immersed in the show’s humor, I hadn’t noticed that right away, but once I got to Portland, it became painfully obvious. But, as I said, more on that later.

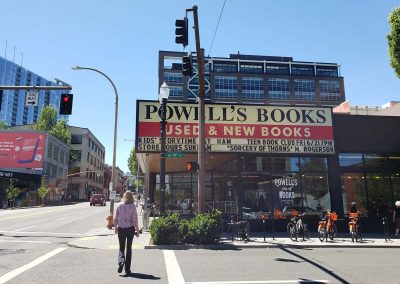

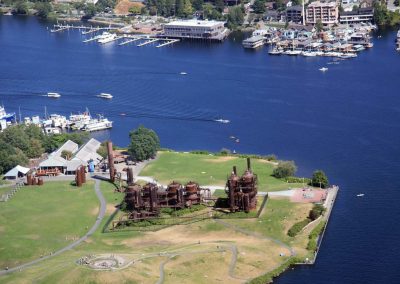

Yes, I did fall in love with Portland. Inarguably, it has so much to offer. Straddling both sides of the wide Willamette River, Portland embraces its outdoor culture and its public spaces, man-made and natural: fountains that double as splashing pools for children, street fests, murals and street art, food truck pods like the Zocalo Food Park being built in our own Walker’s Point, pocket parks dotting neighborhoods whose roads lead into larger parks like the hilly Washington Park, the extinct volcano of Mount Tabor and the even more mountainous Forest Park, the largest urban forest in the country. Mount Hood and Mount St. Helens rise from the horizon. And, of course, I had never felt more free, safe and accepted as a bicyclist ever.

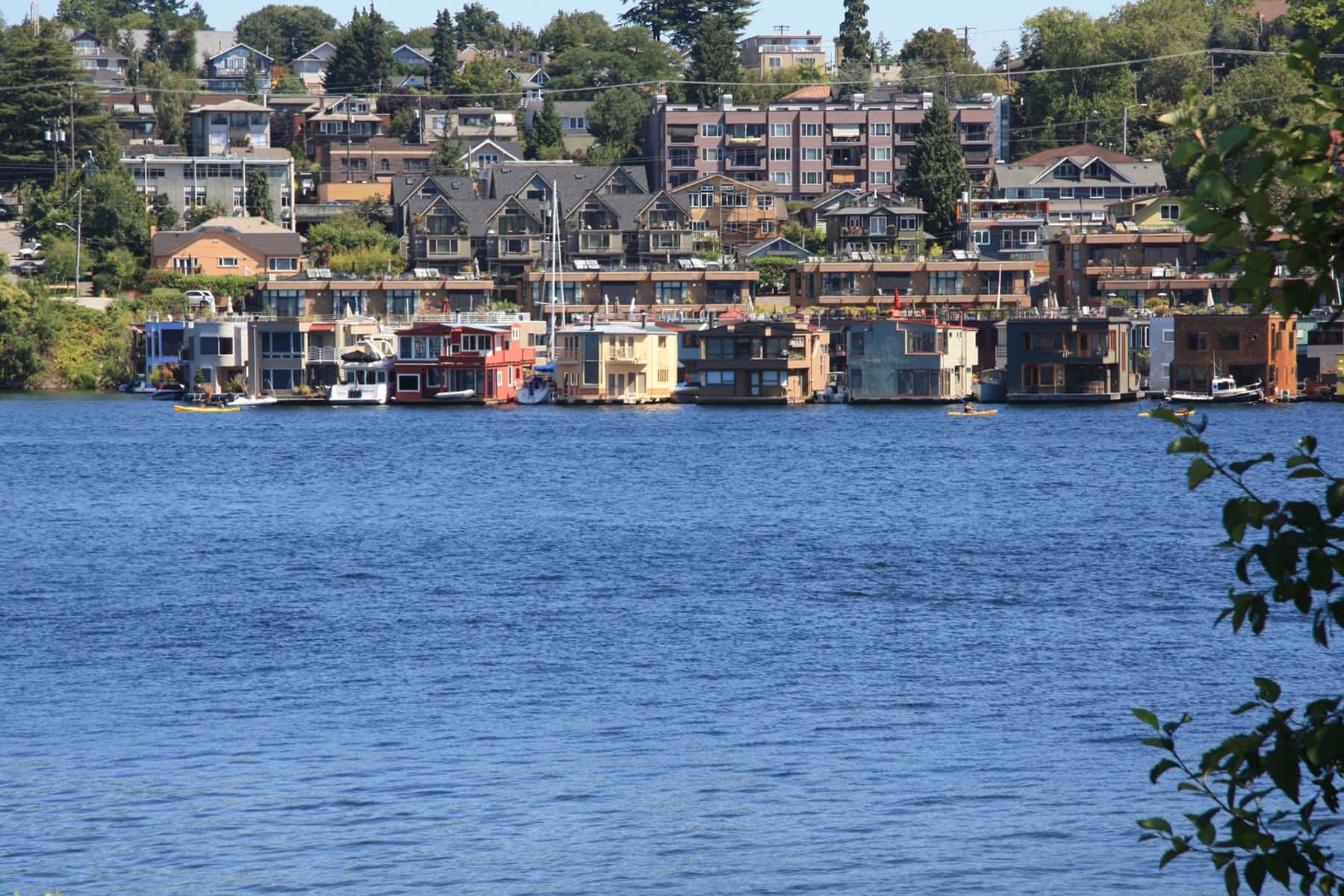

As for Seattle, I grew up there, and it never fails when I revisit the Emerald City that the salty air, the sprawling lakes, the winding hills and the ubiquitous salmon beckon me. I see the Olympic Mountains, the Cascades and Mt. Rainier and my heart melts. I see a ferry boat gliding off to the islands and long to feel the wind in my hair. I remember bike rides and hikes, first jobs and first dates, the smell of seaweed beaches and the Pike Place Market. I feel the tingle of climbing the rollercoaster hills in my rental car or riding to the top of the Space Needle. So for a few moments, I allowed myself to ignore the fact that housing prices in both cities are astronomical, that I’m living the life of an itinerant freelancer here in Milwaukee, and stunning views, fish, bike lanes and childhood nostalgia do not a city make.

A BLACK CLOUD OVER SUNNY SKIES

Despite my excitement about getting away for awhile, I had braced myself for what I was expecting to be a deluge of homeless Portlanders and Seattleites on the streets. Acquaintances recently back from trips to the Pacific Northwest warned me that I would be sad. Portland reports around 4,200 homeless individuals and the city spends about $31 million per year on temporary solutions. Seattle’s King County counts almost 5,000, with the city allocating $77 million per year. Money doesn’t seem to be solving the problem. I didn’t want to be on vacation and feel sad, but I was, of course – so many freeway and bridge underpasses were packed with encampments, individuals with mental illnesses and addictions co-existed with tourists in public spaces and people held signs up to our car windows on unexpected Seattle streets far from the city’s downtown center.

I had to force myself to accept that one, I was a visitor with no obligation to solve a painful social issue that Seattle had been trying to solve for many years to little avail and two, I was on a self-care vacation to settle my mind from a month of city organizing with Jane’s Walk MKE and to spend quality time with my husband, who has had an equally busy first half of the year.

I tried really hard to focus on the positives. Because I have been getting more interested and involved in Jane’s Walk MKE and Safe & Healthy Streets Milwaukee, I secretly planned to make it a ”working vacation” so I could observe the two cities’ pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure so as to compare them with Milwaukee’s. The innovative, multimodal design of these densely populated cities (at least in the parts we visited as tourists) was certainly one of the biggest wow factors of the trip. Mountains, history, fresh air, architecture, art, parks and reunions with my sister and old friends were expected and delivered, but the ease with which we navigated and enjoyed all these things was eye-opening.

A SILVER LINING?

Coming from Milwaukee, which is only recently beginning to embrace multimodal and “complete streets” design, we were delighted to see streets and sidewalks shared, it seemed, equitably – not equally, since cars still dominate – by cars and buses, streetcars and monorails, personal and shared bicycles, shared electric scooters and skateboards, wheelchairs, segways and hands-free, self-balancing personal transporters – especially in Portland. First on a two-hour bike tour offered by Everybody’s Bike Rentals & Tours and then on our own, my husband and I traversed Portland safely on bicycles thanks to the abundance of bike sharrows – bikes and chevrons painted on the streets, gentle speed bumps, bicycle boxes and bicycle-specific traffic signals. And, as people in the Pacific Northwest are known to do, drivers actually stopped for us when we were in crosswalks.

Designated a “Platinum” city – the highest award for bike-friendliness – by the League of American Bicyclists, Portland boasts 385 miles of bikeways that include 7 miles of protected bike lanes, 28.5 miles of buffered bike lanes and neighborhood greenways through residential neighborhoods. The city’s Active Transportation Division has budgeted $5.2 million more dollars to fund 95 more miles over the next five years, with the replacement cost of the current infrastructure, put in place in the 1990s, is $60 million, the cost of about 1 mile of freeway. Over 22,000 of Portland residents bike to work (that’s 6.3% versus the national average of 0.5%), supported by over 60 bike shops, 6,500 bike racks and about 40 bike and pedestrian safety programs at area schools.

Even with all this infrastructure, there are holes. What we observed and witnessed on our bikes was relegated to the North, Northeast and downtown areas of the city, while neighborhoods in what are called “the numbers” lack the same attention. Our tour guide Dan took out a bike map, drew a north-south line down 82nd Street and told us to avoid anything east of there, not because of who lived there but because the infrastructure had been neglected or ignored. While its Complete Streets ethos has been slow, like many major cities, to address the inequities its cycling infrastructure, Portland’s Central City in Motion project promises to address and “promote equity” for people of color, people with disabilities and people who depend on transit.

Seattle, like Portland, has been named numerous times one of the best cities for biking in the country. It already possesses a significant bike network, which I remember enjoying as a youth, and the city has pledged $76 million to increase it to 200 miles over the next six years, mimicking Portlands efforts, connecting the network more successfully and attempting to address inequities in Central and South Seattle. The city seems committed to sustaining its robust bike culture despite having to contend with many natural and political potholes: increased density (120,000 people commute into and out of the city each day to huge companies like Boeing, Amazon and Microsoft), daunting hills, rainy weather, alternative modes of transportation, the infamous “Seattle process” (referring to its lengthy public and political process that can stall projects for years, even decades) and residents’ continued reliance on motor vehicles.

Portland and Seattle certainly have a lot to teach Milwaukee, which only last October signed a Complete Streets Policy into law (Seattle signed in 2007, Portland in 2012), but they are not without their shortcomings and inequities, which was sobering for me. A city can look good on the outside (or on the asphalt) but no city is perfect, despite memories of it or first impressions.

WHITENESS OVERSHADOWS THE ROSE AND EMERALD CITIES

After one day in Portland, my husband and I remarked that we had not seen a single person of color. Seattle was no different. Okay, maybe two. This was a shortcoming indeed. Once I learned about the specter of the two cities’ racist pasts and witnessed the tidal wave of gentrification, the reality of homelessness and inequity made more sense to me. On his “Beyond Portlandia” tour, which promised to explore only non-downtown Portland, Dan revealed who lives east of 82nd Street: the majority of the city’s black population. For as “progressive” and “weird” as Portland purports to be, I’d venture to guess that most people can live out their daily lives without one interaction with a person of color. Whether I expected him to or not, Dan’s tour enlightened all of us about Portland’s white supremacy. So much for a stress-free vacation.

Portland is 77.4% white, 5.7% black, 9.7% Hispanic or Latino and 7.8% Asian. In fact, it turns out that the city and state have never had a lot of people of color to begin with. In 1844, the provisional government of the territory banned slavery but also required any blacks to leave. When Oregon entered the union in 1859, its constitution banned all black people, creating a white utopia where white males could receive 650 acres if single and an additional 650 acres if married. It is no shock that when things changed in 1868 and blacks were allowed to move to Oregon, very few did. By 1890, only 1,000 had moved there. By 1940, fewer than 2,000. It was clear to them that Oregon really did not want them.

During the first part of the 20th century, Oregon could boast the highest per capita membership of Ku Klux Klan in the country. As we stopped for a breather on a bluff overlooking the Willamette, Dan described how despite that threat, 20,000 black workers flooded into the state during World War II to work in the shipyards, their living quarters confined to shanty towns on the river and later to a newly constructed “city” called Vanport between Portland and Vancouver, Washington. 20,000 other transient workers joined the black workers to live in what was essentially the largest public housing project in the country.

After the war ended, however, the black workers were encouraged to leave. The Columbia River made that possible when, in 1948, it broke through into the Willamette and wiped out Vanport in one day. With their homes 15 feet underwater, blacks moved to the Albina neighborhood in the north part of the city, where they were at least allowed to buy houses. As a result, white residents moved out. You can predict the rest of the story: a 1956 arena displaces black homeowners, two freeways split the community, a hospital expands, redlining continues through the 1980s despite national fair housing laws, Albina goes downhill, whites move back in the late 80s to redevelop, gentrification ensues – and now very few black residents can afford to live in traditionally black neighborhoods.

Today, Albina is considered a model for the “new” Portland, full of boxy, expensive condos, bars and restaurants, with much of Portland following suit to accommodate thousands of new millennials at top tech companies like Intel and Google, as well as at Nike headquarters, eBay, Airbnb and Amazon. The median home price according to Zillow is $425,500, with about 60% of white residents owning homes versus only 32% of black residents.

And it certainly doesn’t help that there are almost no black people portrayed in Portlandia in its eight-season run. Luckily, articles such as “After Gentrification: America’s Whitest Big City? Sure, But a Thriving Black Community, Too” have argued that the black community in Portland, albeit small, is working to sustain and recreate a strong community against historic gentrification and recent pop culture whitewashing which conspire to erase it, intentionally or not. If minority communities are going to thrive, then we can’t assume that just because of racism and gentrification they no longer exist.

My hometown of Seattle, too, has a history that we weren’t taught in school including, as in Milwaukee, the history of redlining that so many people are just learning about thanks to, in large part, my colleague at Milwaukee Independent, Reggie Jackson. The “diversity” that I experienced in the Seattle Public Schools was a result of mandatory busing and in no way reflected the segregation that actually existed of which I was only vaguely aware (as in Milwaukee, there was a “North Seattle” and a “South Seattle” and, for my father who worked there, “Chinatown”.

Similar to Portland, black residents only made up 1% of Seattle’s population by 1940. Like much of the country, restrictive covenants in Portland banned black residents as well as Jews, Chinese, Japanese and Filipinos, confining them mainly to the Central District, Chinatown, Beacon Hill and Rainier Valley (where I would have been bussed had not my racist mother not finagled my way into a North Seattle school). Today, the city is 68.6% white and 7.1% black, the median home price is $723,300 according to Zillow and 75% of the land slated for residential development allows only single-family homes to built, keeping away multi-family homes and apartments with renters.

Another fun fact: Seattle resides in King County, which is now named after Martin Luther King Jr. It was originally named for William Rufus Devane King, a Southern slave owner and co-founder of Selma, Alabama, who advocated for the Fugitive Slave Act. The Washington Territory had had strong southern and secessionist sympathies. The name change took a decade to pass the city council.

Nice job, Seattle. It was great learning about you.

RETURN HOME

We did have fun during this vacation in the Pacific Northwest, but it was difficult to do so knowing so many people were homeless. We enjoyed exploring, but it was difficult knowing that much of what we were seeing was the residue of over a century of racism. The same thing could be said about visiting any city or country, I suppose. Like I said, no city is perfect. However, the pedestals I might have placed Portland and Seattle on had certainly crumbled.

I took comfort in knowing that my experience in the Rose and Emerald Cities had been fleeting, that I had just been passing through. It was really up to the people of Portland to handle their future carefully, innovatively and equitably, petals and thorns alike – and up to the people of Seattle to mine for themselves a similar future.

But I’m not passing through Milwaukee. It’s my home, full of imperfections and possibilities. I want to love it even more now, if only to help ensure, in whatever way I can, that we show equal love for all of Milwaukee and that we recognize our past injustices, our current struggles and our potential to be a city of racial equality and economic equity, complete streets and a sustainable future. I wish I could have loved you Portland and stayed in love with you Seattle without reading about your chronic diseases, but I realize you were not much different than my current home, which needs its own sorts of healing.

Good luck, Portland. See you again soon, Seattle. Good to see you again, Milwaukee.

© Photo

Stephanie Allard, Dominic Inouye, Scott Margelofsky, and Lee Matz