When the first whispers of a new virus emerged from Wuhan, China late last year the situation was on my radar. I lived in China for many years, and had the misfortune to experience the conditions of SARS in 2003, the H5N1 Avian Flu in 2005, and the H1N1 Swine Flu in 2009. That firsthand and repeated exposure can make anyone into a Howard Hughes-level germaphobe.

For all the fear and uncertainty that came about from SARS, and the mass culling of livestock over the animal influenzas, the Chinese government never quarantined a city of millions. To isolate Wuhan was an unprecedented reaction to a novel Coronavirus, now known as COVID-19. That action alone made it clear there would be some sort of economic impact on Wisconsin’s trade relationships – aside from the obvious health risks to the state population.

After a Chinese government-style campaign of denial, the American government has begrudgingly admitted there is a COVID-19 problem on homeland soil. Washington state has emerged as the center of the spreading coronavirus, with multiple deaths reported and an increasing number of confirmed infections.

With a full blown and misunderstood crisis now unfolding in the awareness of Milwaukee residents, some perspective for context is valuable. Especially when TV news reports have to dispel internet claims that suggest drinking bleach as a cure to COVID-19. Please, do not drink bleach – for any reason.

China is governed by the Communist Party. It is an authoritarian regime, but not the monolithic institution commonly believed in the West. Like anything involving human nature, greed and ideological created factions. I got a crash course on many cultural intricacies during my first few months of residence.

In the early days of SARS as China was gearing up for the 2008 Olympics in Beijing – still five years away, and after just signing the WTO trade agreement, the wheels of change were creaking forward – but still slowly in early 2003.

I learned about SARS via the pre-censored “Great Fire Wall of China” internet, not long after reports started coming out of Hong Kong. I had been living in China for under a year, so was still adjusting to a new language and culture. Many issues competed for my attention much closer to home than Southern China, primarily the most basic of day-to-day survival in a foreign country where – in a city of millions – I could go weeks and not see another person from the West.

I was aware of SARS, but not by name or its seriousness until April 20. That was when the government admitted there had been a cover-up about the illness. The Mayor of Beijing, Meng Xuenong, and Health Minister were ousted for their mismanagement of what quickly thereafter escalated into a political crisis – aside from the obvious public health issues.

I remember comparing the ham-fisted actions I saw from Chinese officials to the professional disciplines I knew existed in America. With our institutions, there could never be a cover-up of a disease that put lives at risk, especially for something as petty as political gain.

Because of the Chinese system, most individuals were taught to be silent and let a problem pass, instead of looking for a solution to solve it. Germs do not abide by that philosophy. SARS was an embarrassment to the leadership in Beijing, and a long way off from where I was in the Northeast. Until the day it was not.

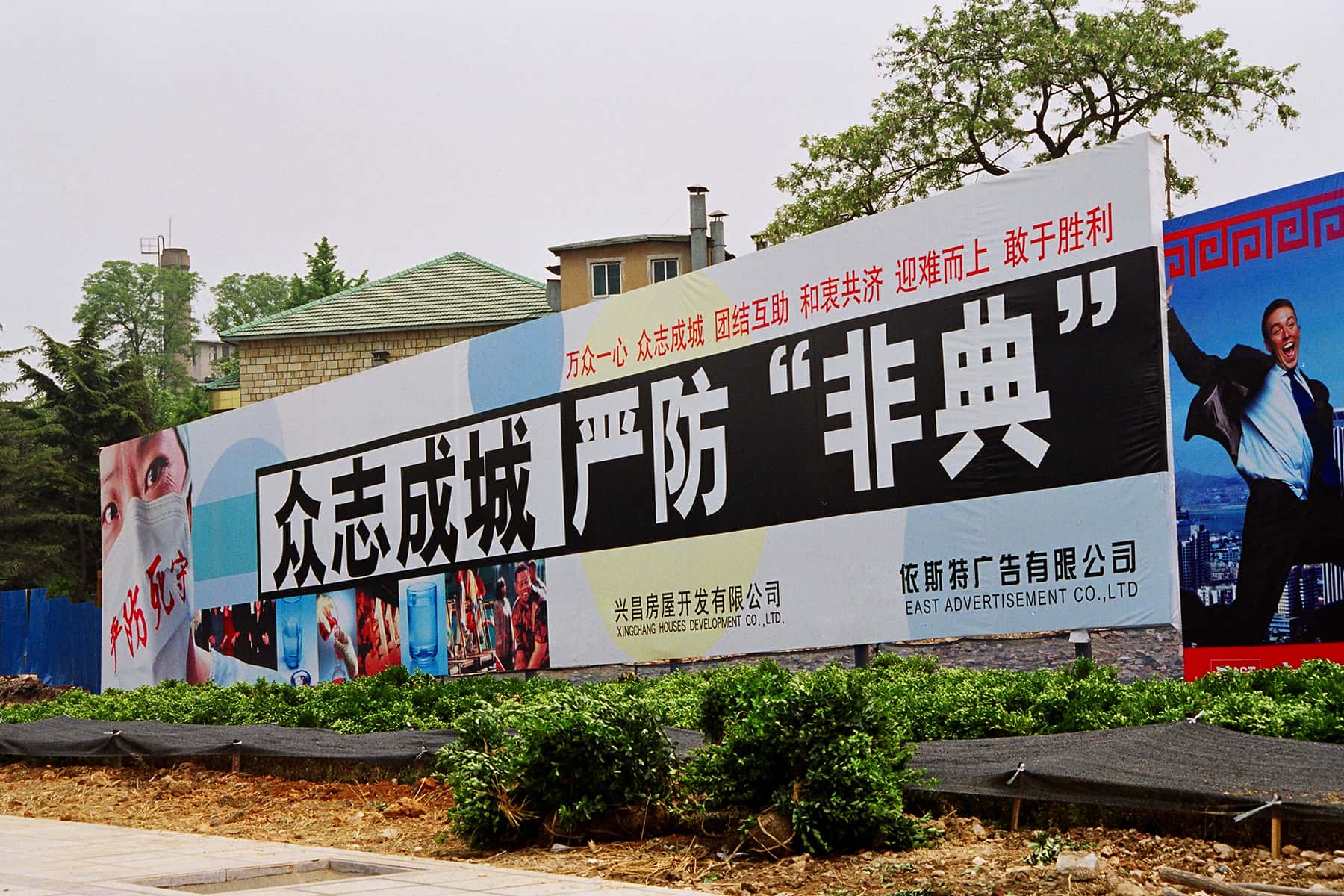

I lived very near the North Korean border with China. Overnight billboards and signs started springing up across the city about “Fēidiǎn” 非典 as SARS was referred to in Mandarin.

The Chinese population at the time was not known for good personal hygiene habits. Not only did they lack access to such products and the personal wealth to purchase them, the culture did not instill such necessities as hand washing. Ironically, when people were sick, they did wear cloth-type surgical masks to keep others from being sneezed on. But hand-washing was not a cultural habit.

Early news reports from Hong Kong had talked about a high concentration of cases, after a residential building got infected. The SARS virus was transmitted via people touching the elevator buttons with unwashed hands.

The situation around where I lived quickly became serious, and hospitals began announcing the growing number of patients they were treating for SARS across the Province – including mortality statistics. University students were restricted to campus, primary schools were closed or reduced class schedules, and I could see a noticeable drop in daily street activity. It was never a ghost town, but the vibrance had been clearly extinguished.

My friends in Milwaukee sent me medical-grade surgeon masks and disposable gloves, because those high quality items were no where to be found in the local shopping outlets I had access to. I used the protection for about a month when the hysteria ramped up, but I was less than methodical about it. A surgical mask is very uncomfortable when wearing glasses, and since the problem matured during the winter, breathing made my glasses fog.

But aside from that period, I never took active measures to protect myself other than washing my hands often – a necessity for the grime of city life anyway. For months I carried a mask and gloves in my pocket, just in case, and retained the unused supply for years after – until I left China.

At the time, I kept the stash for when the situation got bad. It never really did – for me, but perceptions of impending doom did flair up. I was very much influenced by others around me, and the uncertainty of the unknown. I was always distrustful of the Beijing government, even after my Mandarin improved and I could clearly understand how I was being lied to. But I remained fairly calm about the problem of SARS and its risks. I did not look for conspiracies and was proactive in learning and confirming what information I could get. I ultimately reasoned that when everyone around me began to freak out, then it would be time for me to become concerned.

SARS was a scare, due to the growing and interwoven nature of the global economy. But it never developed into the kind of superflu from Stephen King’s “The Stand.” Lack of information and misinformation, however, severely contributed to most of the anxiety I witnessed – and the social damage it caused.

The health situation eventually stabilized by 2004, but I continued to feel the cultural impact. That had a direct influence on my personal habits. SARS was just a natural evolution of the unsanitary conditions I constantly navigated. For example, tap water is not safe for anyone to drink. Before I could buy good foreign-made water filters locally, I had to boil water daily. Actually, even after I had the filters installed I continued to boil water for years because I had been taught to not trust the filters. My morning ritual of boiling water is how I finally developed the habit to drink coffee.

The fear of SARS faded, until the Avian Flu arrived in 2005. Every night the news broadcast on state TV showed individuals in white hazmat suits culling tens of thousands of chickens on infected farms. By 2009, it was the Swine Flu, and those white hazmat suit people were torching pigs. The pork industry suffered because that is the most favorite meat of the Chinese people. Reports surfaced that farmers were selling sick picks to cut their financial losses – without regard to the health of the public, which did not help contain the problem and only made the population more nervous about their health or who to trust.

A full blown panic never erupted, but the experiences took away what little confidence people had at the time. My life would get back to normal until another rumor of another health scare arrived, and the trigger would cause a PTSD-like reaction. I saw this in others close to me, who were far more used to being stepped on my their government.

I could not exist in that kind of environment and not be affected. But as a foreigner, some things affected me very differently – or at least did not provoke me in the same way. And some of that conditioning remained dormant until I returned to America.

I never had a panic-attack, meltdown, or Howard Hughes moment, but there were occasions when I felt extremely uncomfortable. Like the time someone in my office picked up my iPad and started using it. He touched the glass surface, then his face, then the glass again to scroll or swipe. I could not use the device again until I had sufficiently cleaned it. Also, being around children was not my favorite thing. The sneezing mucus that splattered around made me want to wear a hazmat suit, so I tended to keep my distance in the early days. The 2011 Steven Soderbergh film “Contagion” really did not help me adjust back to American life, because it too closely resembled my experience in China. Nor did my time in Alaska, when I was routinely exposed to potential Gastrointestinal (GI) infections onboard ships.

America of 2020 is not just more connected than it was in 2002, but also how we interact with the world. The iPhone came out in 2007, two years after SARS. Now, everyone has a touch-screen mobile device. Our culture forgets how many things we touch in public. There is no longer a public phone booth, thankfully. But my Milwaukee bank branch has “video tellers,” which is an ATM and a video screen that is supposed to provide personal service via a machine. The system uses a traditional pay phone-style handset, which get high levels of usage from people using the bank’s services. I am forced to use the system too, but it is still an uncomfortable situation.

There is not a public hysteria over COVID-19 yet, but anxiety is brewing. It does not help that a great deal of political disinformation is coming from Washington DC. For me it is Déjà vu, but I am home and do not need to translate what is being said. Even so, I do not understood what I have heard coming for the Trump White House, because it is illogical, unscientific, and puts his political interests above the health of the nation.

“I have been speaking to experts for the last few days, and the response thus far has been a terrible failure. There has been a complete failure to deploy accurate testing at a scale that is necessary to get your arms around the scope of the epidemic. The political leadership has sent the message to the bureaucracy and to the public, that they want this to go away. They don’t want it to be a big problem. They don’t want the markets to tank. And they don’t want it to hurt the economy. The fact of the matter is we have already learned from the trail of the pandemic from China to Iran, Korea, Japan, and Italy, that the worst thing you can do at the front end of this is tamp down and deny the scope of the problem you’re dealing with.” – Chris Hayes

Amazon.com has sold out of disinfectants, gloves, and masks, as Americans have become more aware of CONVID-19. The CDC has advised that anyone exhibiting symptoms of coronavirus avoid public areas as much as possible, and seek medical attention. Yet Trump’s autocracy continues to foment conspiracy theories about the virus, dismissing news about it as a “new hoax” that targets him.

The ineptness of the federal reaction has only fueled the unease, uncertainty, and confusion for a population that has not been exposed to this serious type of epidemic before. The usual reaction brings panic and blame for the wrong people. Pointing a finger never medically cured anyone, but has certainly caused enormous harm.

Federal leadership has also done little to prove it is prepared or professional enough to deal with the ongoing situation, let alone a full blow crisis. And because there is currently no vaccine for COVID-19, anti-vaxxers have one less hoax to spread in support of their cause.

The Milwaukee Independent has been reporting on COVID-19 since late January, and was the first local news outlet to do so. The problems in China are a long way off to the people of Milwaukee. It took less than two months for that problem to get here, with Wisconsin reporting its first case of infection in February.

Experience in China with SARS is no indicator for what will happen with COVID-19 in Milwaukee, but there are already clear parallels. In part with how the illness spreads, but more specifically with governmental management and pubic reaction. So much of what I witnessed in China during my youth prepared me for life in America as an older adult, which is a sad irony.

I believe how we – as a local community and nation – respond to this problem will show a lot about our character. It will expose our faults and weaknesses too, but my sincerest hope is that we have a chance for healing and redemption as the situation develops. Just maybe we can rise above our limitations instead of melting down because we are imprisoned by them.

© Photo

Lee Matz and 波吴