The Bugle-American was an underground “hybrid” newspaper founded in 1970 by four young UWM journalism grads Dave Schreiner, Denis Kitchen, Mike and Judy Jacobi during the Vietnam War era.

The publication lasted seven years from 1970 to 1977 by providing aggressive local political and cultural coverage by attracting a strong line-up of contributors and loyal readers. A distinctive feature for the first two years was a full page of homegrown comic strips, unprecedented in America’s underground press. Co-founder Denis Kitchen’s separate publishing company, Krupp Comic Works/Kitchen Sink Press, made “The Bugle” the flagship paper for weekly strips created by its local cartoonists. Back issues of “The Bugle” tend to be sought either by comics collectors, nostalgic hippies, and history-minded Wisconsinites. This issue is from the Milwaukee County Historical Society’s collection. The text has been transcribed precisely as it was written without any edits. It is presented here as a snapshot from the recent past to provide content for current events that continue to affect the local community.

THE KLAN IN WISCONSIN: a report, by Marty Racine

The Bugle-American, Volume 6 Number 11 (Issue 196) March 19, 1975

“Ku Klux Klan” … The gothic name evokes images ranging from stark terror to paternal benevolence, and it lives 110 years after its birth for lots of reasons, not the least of which is the sound of its name. Can you se the “Jolly Joker” or “The Honky Protective Society” or some such existing for so long?

The Klan is having a resurgence today which is not easily defined by numbers or intentions. The change is being noticed more in the North because the South is the seat of prejudice, right?

Two newsworthy events in recent weeks are the Klan’s involvement in the school busing fracas in Boston, and a series of racial flareups at the Eastern New York Correctional Facility, a medium security prison, where reportedly 15 to 20 guards are Klan members.

In Wisconsin, the Klan is underground, tightly-knit, and secretive. The FBI refuses to speculate on the size of membership and information on the Klan’s activity here is speculative. Some of the best educated guesses on the Wisconsin Klan comes from Tony Michetti, former member now working at the American Motors Plant in Kenosha. Michetti belonged to the Kenosha chapter of the KKK from 1953 to 1963, and says of his former group: “They’ are all underground now. I believe there’s organization and they could perhaps be bigger now than when I was affiliated with them.’

To better understand the Klan today it’s necessary to look into its beginning.

In December of 1865, six former members of the Confederate Army banded together to “bring peace and happiness” (law and order?) to the South which they felt politicians were either unwilling or unable to do. The thrust for the foundation was supplied by Captain John Lester of Pulaski, Tenn., and the six who formed the “Pulaski Circle” comprised the first of numerous “Dens” into which the Klan would later be organized.

The Ku Klux Klan was one of the many secret “protective” societies whites formed in the South during Reconstruction. The name was taken from the Greek word “Kuklos,” meaning circle. That was changed to “Ku Klux,” with “Klan” added to produce a name sounding like bones rattled together. If there ever was a clue to the intentions of the Klan, that was it.

It was painted in the public mind as a group that didn’t mess around. The secrecy, rituals and grotesqueness of the sheets and hoods aided that image. It was mostly for effect, though. At first it began as a fraternity ritual rooted in confusing and frightening the public for social amusement only, ha, ha.

It wasn’t long before the Klan’s waves rippled throughout the South, and the hooded night riders began resorting to violence against both blacks and whites. The important thing is to recognize the social, cultural and economic conditions which, in the years 1865-67, made fertile ground for Klan violence.

Most of the recruits were young men of Scotch or Irish decent, with a lot of time on their hands following the war. They lived in a region stretching from Virginia to Mississippi which endured the worst physical destruction and social and cultural upheaval fro the war.

Starting in 1867, act after acts of looting, burning and murder by both blacks and whites occurred across the South. Generally, Souther whites did not so much hat blacks as a race, they just wanted Unionists and Northerners to go away and stop encouraging the Negro from enjoying the first tastes of freedom. The bigotry displayed by Southern whites was manifest in the fear that the Negro was ignorant enough to be led by rabble rousers to foolishly want to have the same rights the white man had.

The process was a simple one whereby the Klan initially directed its fear and anger against “alien whites of low character” who helped the blacks for into Union Leagues. Whites had visions of roving bands of blacks slaughtering entire neighborhoods as their way of gaining property. The KKK felt their organization encompassed all the resistance to the “Africanization” of the South during Reconstruction. As one Klansman wrote, “Nearly all prominent men (ex-Confederates) in the Souther States are connected in some way with the Klan.” What he probably meant was that, as the Klan grew and its mystique spread, nearly all the southern whites adhered to its state of mind. But the Klan’s secrecy prevented the general public, even in the South, from knowing much about it.

By the end of 1867, actual Klan membership was estimated at 550,000 all in the South. Its habit of running around at night in large groups, doing spectacular and violent things, made it seem larger. The original fun and games of the Pulaski Circle had evolved into dens which dotted the South. For awhile, they were quite effective. The activities of the Union League were moderated and the Souther brand of law and order was partially restored.

Three elements helped the Klan spread. First, there was the notion among members that they were enshrined with some divine mission (all were Christians) which fostered great expectations. Second, its mystique played easily on a curious and receptive public. And, of course, there was the conditions of the time.

In grudging respect to the Klan’s founders, they foresaw and hoped to avoid the excesses of violence which by now was beyond control of the Pulaski Circle. Lester and his friends decided to centralize the organization in 1868 because it had grown too large to disband it. Out of a convention came a constitution, by-laws, oaths and rituals. But it did little to dent the violence.

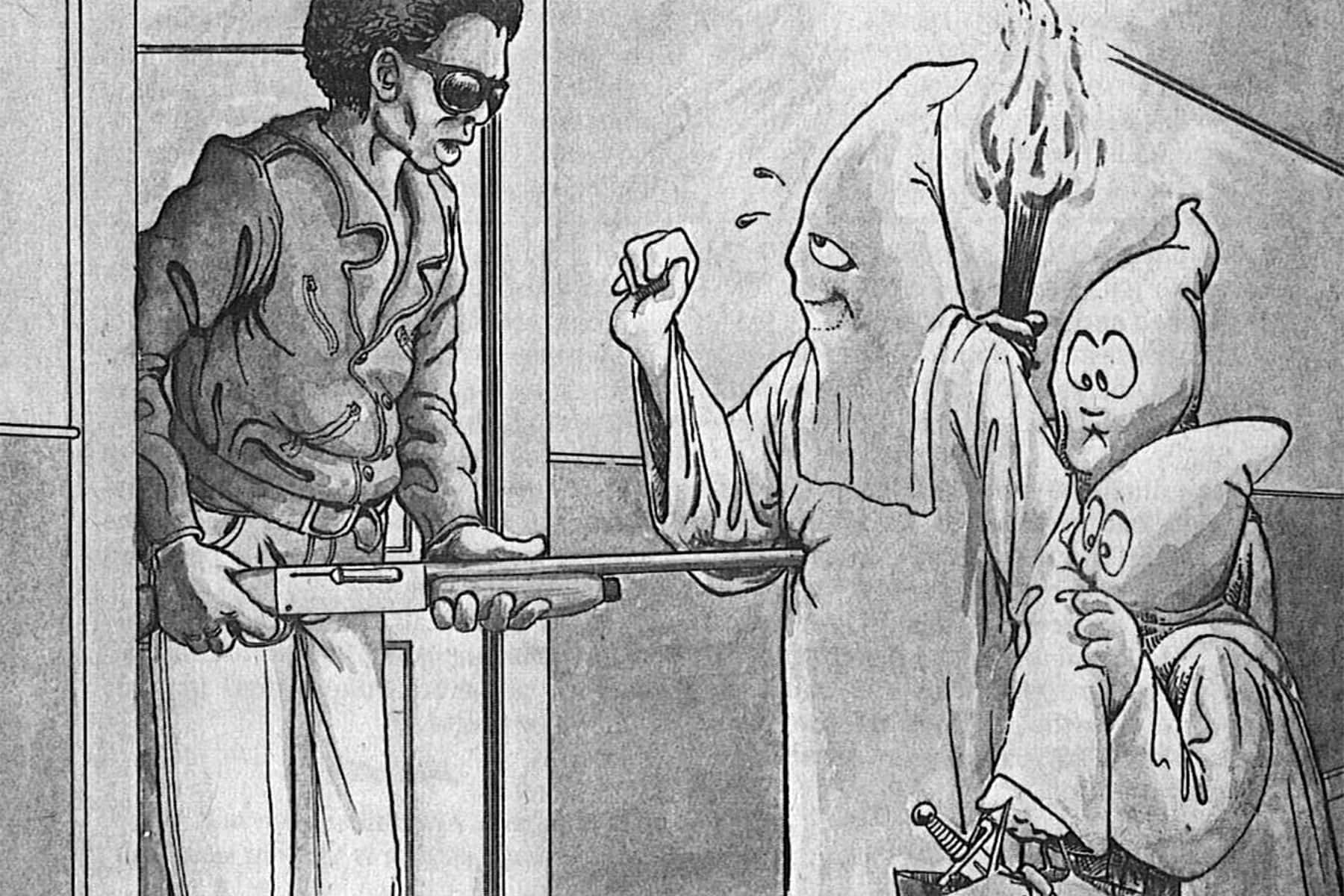

The usual practice was for a Den to hold a meeting once a week to discuss the fate of any individual enemy and take a vote. What followed was either murder or the threat thereof. Often a threat was sufficient, mainly because of the bizarre behavior of the Klansmen when they got cranked up. The would don their uniform consisting of a white mask, tall cardboard hat and a gown or robe of any color, suit your taste. The more grotesque, the better. The tall hats imparted the illusion of size as the gowns flowed in ghostly horror as horse and rider bore down on a victim. With the addition of a cross burning and other rituals the Klan became as much a state of mind as a tangible organization.

In 1868-68 the Klan’s influence, mystique and sheer size were at their peak, even to this day. Most Southern politicians were either members or sympathetic. But, as excesses continued, more people began to strike back. Awe and curiosity were turning to hostility and Washington was starting to investigate and infiltrate. By late 1869, the Klan’s leaders decided to lay low, even to the point of burning documents, costumes and all important materials.

Any sociological event is wrapped in the boundaries of history. The time was ripe and the Klan was born as naturally as life itself. It grew healthy on turmoil and burned itself out five years later. It was a product of history and took advantage of it, but by 1870 it had become subservient to it. It had grown from a “peace keeping protective force” in 1865 to a band of outlaws in 1869. It wasn’t till history provided another opportunity did the Klan ride again. The year was 1915.

The Klan’s resurgence was fueled by two things, not necessarily equal. One was World War I and the years preceding it. The other was a film which, as far as the Klan was concerned, was a masterpiece of propaganda.

The film was D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, which showed (through the mind of its Kentucky born and bred director) the Civil War and Reconstruction Era in the South. From out of it came a picture of the Klan as noble night riders, protecting fair maidens from the ravages of the newly-freed blacks, who were portrayed not as only running after white women but as taking over the very government in the South. The picture met with a storm of controversy and was tremendously popular, in big and small town, North, South, East and West. The movie had been adapted from an unsuccessful potboiler play called The Klansmen, but Griffith’s great artistry combined with his Southern view and the material to make an incredibly broad and sweeping film, of which the romanticized Klan was a very important part. To underestimate the power of the film’s propaganda value to the Klan at the time would be a mistake.

William J. Simmonds, a circuit minister from Alabama, began spreading the Klan gospel west of the Mississippi. World War I bred suspicion of aliens and ethnics so the Klan promoted 100% Americanism. Also, blacks were moving into industrial cities of the Midwest, especially St. Louis, Chicago and Detroit, and the Klan’s bigotry followed them. After WWII immigration increased and the cities were becoming melting pots that did not melt … perfect ingredients for a new, urban type of Klansdom.

The Klan’s wrath in 1915 was not only directed at blacks, but also at Jews, Catholics, Orientals and life styles, (dope, liquor, night clubs and even sex). That all-encompassing prejudice was similar to other so-called fraternal organizations.

By the mid-1920’s the Klan had chapters throughout the country with strongholds in the South and Midwest, especially Indiana, where they threatened to take over the state government. However large the membership, Milwaukee and parts of Wisconsin added only a small share.

Wisconsin was not as receptive to the Klan as other states and, in fact, the first chapter was on bad terms with Atlanta headquarters from the start. The elements which shaped the Klan in the 1920’s were not as prevalent here. “Americanism” in Wisconsin was not seriously under attack, because of the small number of blacks, Jews and Orientals. Even lingering wartime suspicion of loyalties, fears of La Follette Progressivism and Milwaukee Socialism did not provide a primary breeding ground. Mostly, Wisconsin Klansmen were anti-Catholic, and even that hostility wasn’t as great as elsewhere. According to one member at that time: “What Wisconsin Klansmen wanted was a fraternal lodge for native born white Protestants that would offer a little ritual, a little discrimination and a little gemutlichkeit.”

The first KKK chapter in Milwaukee was organized in the fall of 1920 among carefully selected business and professional men. The first meeting was on a US Coast Guard cutter, and subsequent meetings were in a hall over the Pabst Theater. Shortly after, unites were established in Kenosha and Racine. The three groups were much more secretive than elsewhere.

Because the Milwaukee chapter was small it remained on a “provisional” status with the national organization. That meant local dues and funds were siphoned to Atlanta. Members walked out in 1921 when they were refused an accounting of local monies but although the money squabble was never resolved, they returned when promised a new leader of their own choosing.

He was William Wiesemann, a local insurance man prominent in Masonic circles. Shortly after, the Milwaukee membership swelled to a peak of slightly more than 10,000 by 1924. A permanent home was purchased at 2424 Cedar St. Still, Atlanta refused to lift the provisional status and the members revolted again, leading to an eventual waning of the strength of the Milwaukee chapter. It has not since been as potent. Klansmen were fractionalizing into conservative organizations such as the Knights of American Protestantism, the Minutemen and various other anti-Catholic groups. One of the more curious aspects of Milwaukee Klansmen was the number of Socialists who joined, despite the protests of Socialist leaders. Again, the common bond was anti-Catholicism.

Elsewhere in Wisconsin Klan activity was pretty much limited to parades and rallies in the ’20’s. Its influence outside Milwaukee was confirmed to Madison, Oshkosh, Racine, Kenosha and Chippewa Falls, where it did well on local elections. The American Legion in Wausau asked Klan organizers leave town and in Waukesha a mob stormed the Continental Hotel in 1924 when the KKK held an organizational meeting. Klan rallies and parades were heckled and broken up in Boscobel, Chippewa Falls and Marinette.

Against the tide of La Follette Progressivism the Klan fared poorly in state politics and political leaders remained hostile. The best showing by a Klan member in an election was by Dan Woodward when he wound up third in a US Senate race, collecting 40,000 votes. Other than there were two prominent state politicians on friendly terms with the Klan. One was Governor Fred Zimmerman who was avowedly anti-Catholic when he had been Secretary of State.

The other was the mayor of Madison, whose support was returned with an offer of assistance by the Klan’s military force, the Kavaliers. The offer was turned down. The KKK had a vested interest in cleaning up the “Little Sicily” section of Madison, which may well have been the most visible target of violence schemed up by the Klan here in the 1920’s. While the police and district attorney refused their offer, the mayor had at his disposal a few city policemen and detectives who were outwardly members of the Klan.

KKK membership in Wisconsin and the nation had peaked by the mid-20’s and, by 1932, the last Den was dissolved. For the next thirty years activity was virtually non-existent. The situation reached a point where, on December 10, 1946, the state Supreme Court annulled all corporate rights, privileges and franchises of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

In the early 1960’s membership could be counted only in the hundreds, there was no organization and no official chapter. The first glimpse of any Klan activity came in 1963 with the burning of a cross in front of a black-owned shoe repair shop in Waukesha. A person later identified as David Harris was charged with a misdemeanor for the act, and sentenced to 30 days. Harris, a Waukesha truck driver, surfaced two years later as the apparent sole force to revive the KKK in Wisconsin, when he placed an ad in the personals column of the July 7, 1965 edition of the Waukesha Freeman. The ad said the Wisconsin Ku Klux Klan was now open for membership, and Harris later told reporters he received 48 inquiries.

At about the same time, Robert Shelton of Alabama, the Imperial Grand Wizard of the Klan, grandly announced that national headquarters would soon be assisting organizing efforts in Wisconsin. He never delivered on his promise and in August, Shelton said the Klan had no official spokesman in Wisconsin. The group suffered another setback on October 11, 1967 when Secretary of State Robert Zimmerman turned down another proposed Articles of Incorporation presented by Harris. According to the Articles the purpose of the Wisconsin Ku Klux Klan would be to “promote harmonious and peaceful relationships among the citizens of Milwaukee and its environs.”

Harris announced after the corporation failure that the state Klan would disband and burn all records. The announcement gave the impression that the Wisconsin Klan was organized and bigger than it really was. It also took some heat off Harris, whose organizing efforts and PR work were finding only police investigations rather than public support. Harris’ Waukesha home had been the target of a shotgun blast the previous year.

In the mid-60’s membership rallies and public appearances by Klan members served only to show how few there really were. Despite this, sporadic acts of violence flared up in the Milwaukee area, the first being the fire bombing of Allied Linoleum Company on South 16th Street. Apparently, the Klan figured it to be a Communist front, as the owner, John Gilman, was the former executive director of the old Wisconsin Civil Rights Congress.

Illinois Grand Dragon Turney Cheney was convicted in the case and sent to prison for the maximum 15 years, with state testimony coming from Robert Schmidt, 42, of Milwaukee, who also participated in the bombing. Schmidt later pleaded guilty to the bombing of the Milwaukee NAACP office on West Center St. on August 9, 1966. This time he was victimized by a co-conspirator, Roger Long, who was given immunity from prosecution.

On March 10, 1967, The Calvary Baptist Church in Milwaukee was gutted by fire. The paster was president of the Wisconsin NAACP. The fire inspector determined the cause to be an over heated steam pipe.

In all three bombings/fires no one was injured, no one intimidated, and the Klan’s intent, whatever it was, was not realized.

In the late 60’s and early 70’s suspicion grew that several Milwaukee policemen belonged to the Klan, especially after an NAACP worker was shot by a police officer. Harold Breier refused an investigation, and that was that. At the same time it was learned that six policemen on the Chicago force were Klan members.

Today, the Wisconsin Klan has a small membership, organization is on a local level rather than directed from a monolithic national headquarters and any unit is underground. With the risk of being too general, the typical Klan member lives in Milwaukee, Racine or Kenosha. He’s not highly educated and works in a factory. He’s disenchanted with the political scene and he’ not happy with current social conditions. He’s expecting the Revolution. He believes in the ordained durability of the Ku Klux Klan.

Tony Michetti, who I mentioned before, got out when the going was bad. He was disillusioned. He realized that violence done by certain members was stupid, and his affiliation hurt his personal, day-to-day life. But his philosophies have changed little, he says. They appear to be rooted in an almost romantic century-old consciousness which gave birth to the Klan back in Tennessee.

If Tony’s beliefs are basically the same as when he belonged to the Klan, they might represent these of the Klan today. How accurate are they? That’s for you to decide. Following are his thoughts on a variety of subjects, recored in a conversation three weeks ago.

On his personal opinion of blacks: “Hell no, I’m not prejudiced against blacks. I’m prejudiced against people who want to make me a slave, yes. I’m prejudiced against any group that wants to Lord it over others … I’ve got colored people in this whole neighborhood and they’re all my friends and the only time I get a dirty look or anything was when the news media came out and reflected on what I belonged to. But if they knew my ideas they would still like me.”

On the Klan’s opinions of blacks: “They don’t look at them as a problem. How much discrimination in the world would there be if there were no such word? The didn’t believe Negroes should be killed or done away with. And I still say that all this news and these pictures that you see are biased. The Klan didn’t believe in inter-mixing or inter-breeing. I don’t believe that the Klan felt that the Black man was a threat as far as the individual is concerned, but when we’re talking about groups that are led and instigated and motivated and sued as blocs, now you’re talking about a different thing. You’re talking about a group of people who aren’t too highly educated, that are led to believe that because I’m gonna lead you, I’m gonna get you everything, a utopia, at the expense of the other man, even … that’s how far they’ve gone today.”

On Klan Violence: “The Klan believes America was founded as a Christian nation. They are religious, they believe in Jesus Christ, they believe in a God. Aside from that they’re not doing anything violent … you don’t hear of them doing anything violent today. Now awhile back there were some people who claimed they were in the Klan and got out of line. But they went to court and got found guilty. But those people took the matter in their own hands. They did it deliberately, they have themselves to blame. At that time they had a tight lip on it and I didn’t even know about it until after it all took place. They were very reckless, stupid, idiotic, and they paid.”

On the media’s treatment of the Klan:, and its image: “What you’ve been told and have learned and been shown about the Klan is not the way I see it, even to this day … the propaganda made it that way, like Metro Golden (sic) Mayer.”

On current Klan power and organization: “I would dare say their membership has gone way up since my day. I’m only guessing. I don’t associate with them anymore nor do I wanna know, but I believe they’re more powerful than what you would ever dream. I’m very well aware of the fact, too, that the FBI can’t infiltrate them in the North, not too easily like they can in the South, because people down South are more trusting, more open and warm hearted. Up here, they’re not trusting, they gotta know you well. At one time they, (members) had to have a card in the South, they still do, but up here it is totally and strictly underground. I do know things are very closely knit. They’ve had to keep the bad elements out.”

On Klan intentions and preparedness: “I believe the Klan could give the United States a hell of a battle if they ever mobilize … If it came down to internal strife or revolution I hope they’re psychologically prepared, because I believe they are. They’re not gonna be the first ones out there with their guns, no way … They’ll just sit back and let things happen. They’ll wait for the mop-up, that’s what they’ll wait for. And they do not instigate these riots, understand. The do not like the Father Groppi or Marlon Brando, all the protestors that agitate, and are against that. But when it comes to the nitty gritty I am sure they may be massive.

On politics: “The time for politics is long gone. Who are you gonna go to, the Democrats? The Republicans? What about the American Party. They’re just opportunists, too. They’re not out to do any good for this country of the people in it. If they (KKK) see a chance or a breakthrough to recapture this country by politics they would do it, but they’re more realistic than that, they face up to reality. These are levelheaded people … There is no leader right now that would take this country and lead it. Th Klan believes that America is a country for the people, by the people and of the people, and not a bunch of international bankers. If that’s a political philosophy, so call it. I doubt very much if a Klansman would run for office today. If he would want to get into office look what he’d be up against — all the one-worlders.

On the John Birch Society: “The Klan didn’t lose any men to the John Birch Society, let’s put it that way. But it might have kept many form joining. What does the John Birch Society do besides have meetings and stuff? If we ever take it over they’ll be the smartest people in the concentration camp. I don’t think they plan on physically taking up arms or anything. I don’t think they could be considered a militant group.”

On who’s the enemy: “The biggest enemy is the FBI and the Internal Revenue Service, because the IRS collects the taxes by which they’re gonna hang us. We finance our own destruction. You earn it honestly and everything, but you gotta pay it and the FBI is the watchdog to see that you don’t, say, counterfeit money … and they maintain the system. You’re not supposed to rob a bank, but yet the bankers rob us. This is legitimate, with pen and ink. You use a gun and that’s violent and shouldn’t be tolerated, but they have the pen and ink and they have the judges to say they’re all right in doing that.”

On freedom: “We’ve lost our freedom. To hell with power, I don’t want any more power than you have, but we’re being controlled.”

It can only be said that these statements probably weave sometimes left, sometimes right and sometimes in the middle of Klan philosophy. But what is the philosophy? It’s embodied in the sum of the beliefs of every Klan member, and for that reason it’s nebulous, it can’t be tracked down. It can be explained, maybe, by events. It can be placed in the perspective of history. It can be interpreted psychologically. But the only pure Klan philosophy rested in the head of Captain Lester in Tennessee in 1865, and it’s not certain he recognized it. By-laws, oaths, rituals and goals are written out, but they are only the surface. Their prejudices have always been there, they are not as attractive to society as they were a hundred years ago, and they have ultimately done little to deter blacks and other minorities from striving for equality.

It might be fair to say that the Klan wanted to preserve the dubious privilege of a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant to declare himself superior to the rest of the population and to define Americanism in his own traditions and interests.

Marty Racine

The Bugle-American, Volume 6 Number 11 (Issue 196) March 19, 1975

A copy of the original publication was provided by the Milwaukee County Historical Society