The Marcus Center’s architect left one of America’s most varied and far-reaching legacies, including blueprints for thriving urbanism.

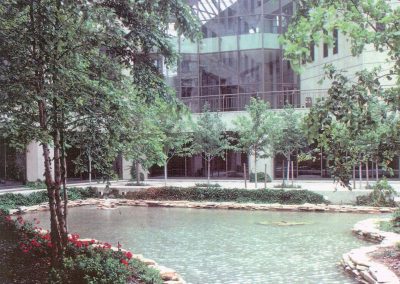

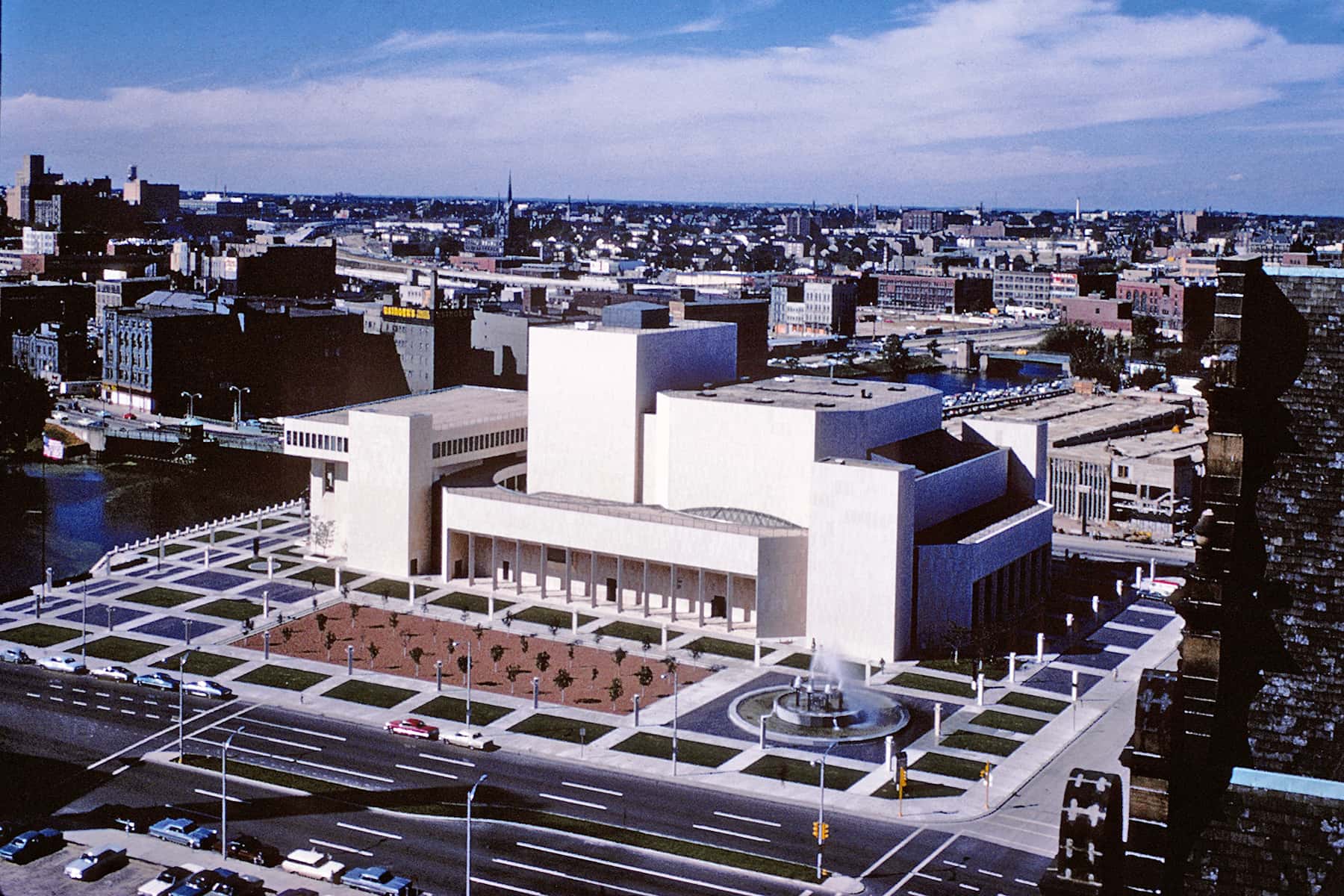

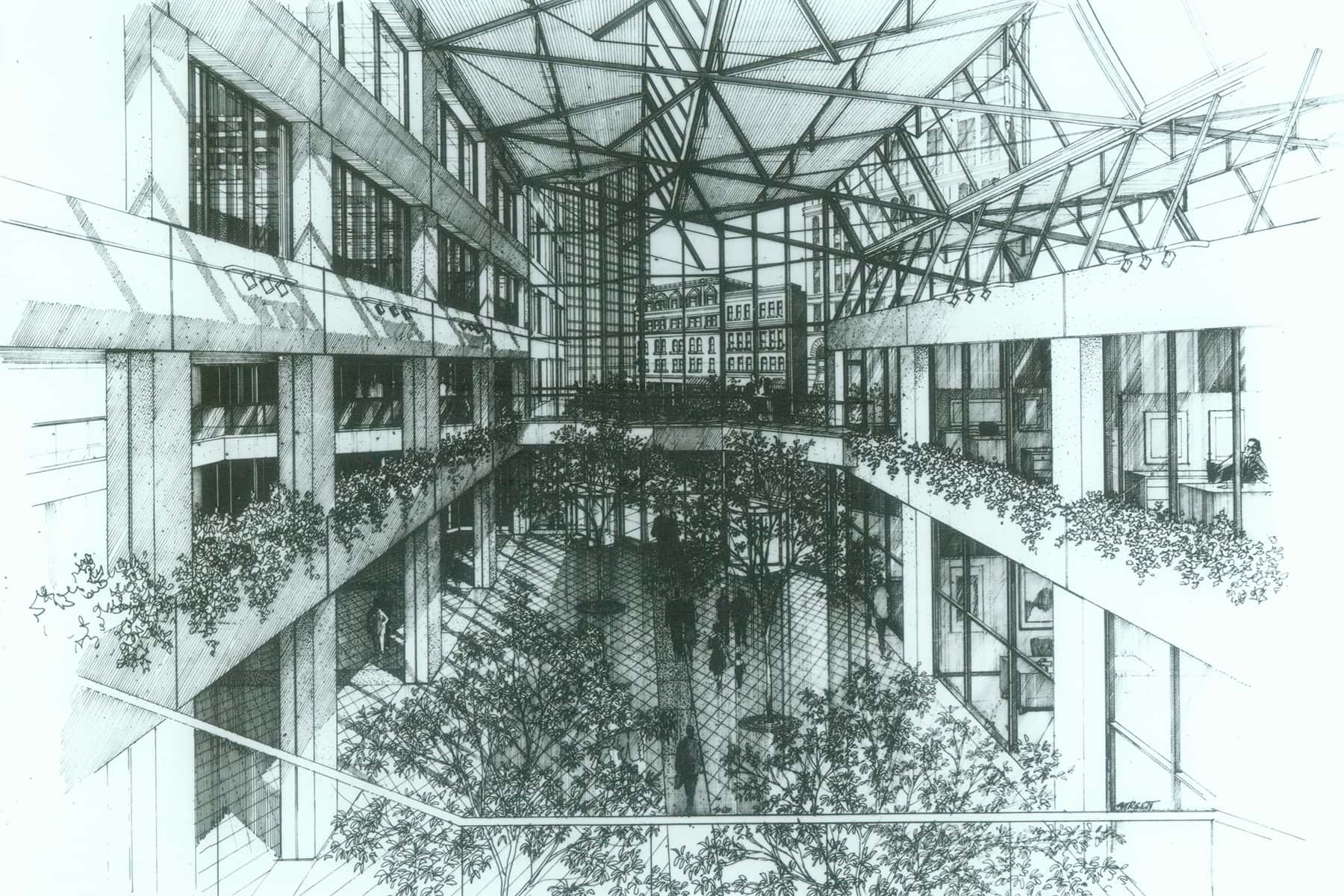

If visionary architect Harry Weese had never worked in Milwaukee, Downtown would not boast three imaginative buildings. Each was distinctly different from the others: the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts on Water Street, the 30-story tower and atrium called 411 East Wisconsin Center, and the former IBM building at 611 East Wisconsin, recently sold to Foxconn for $15 million. And yet, despite having built striking and well-used buildings, Harry Weese’s name seems little known in the Cream City.

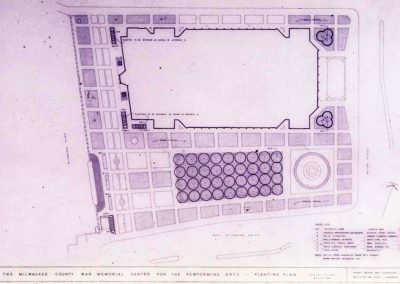

If Harry Weese had not been chosen to design what was originally called the Performing Arts Center (PAC), we would likely not have a Dan Kiley-designed public plaza and horse-chestnut grove surrounding the Modernist cultural hub. Nor might we have two public parks flanking that civic center on the west and east.

That was because Weese and Kiley studied the whole area surrounding what is now called the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts, and developed a plan for making it a well-linked and expansive heart of Downtown. They advised how to intentionally connect both sides of the Milwaukee River, City Hall, and the Pabst Theater to the PAC.

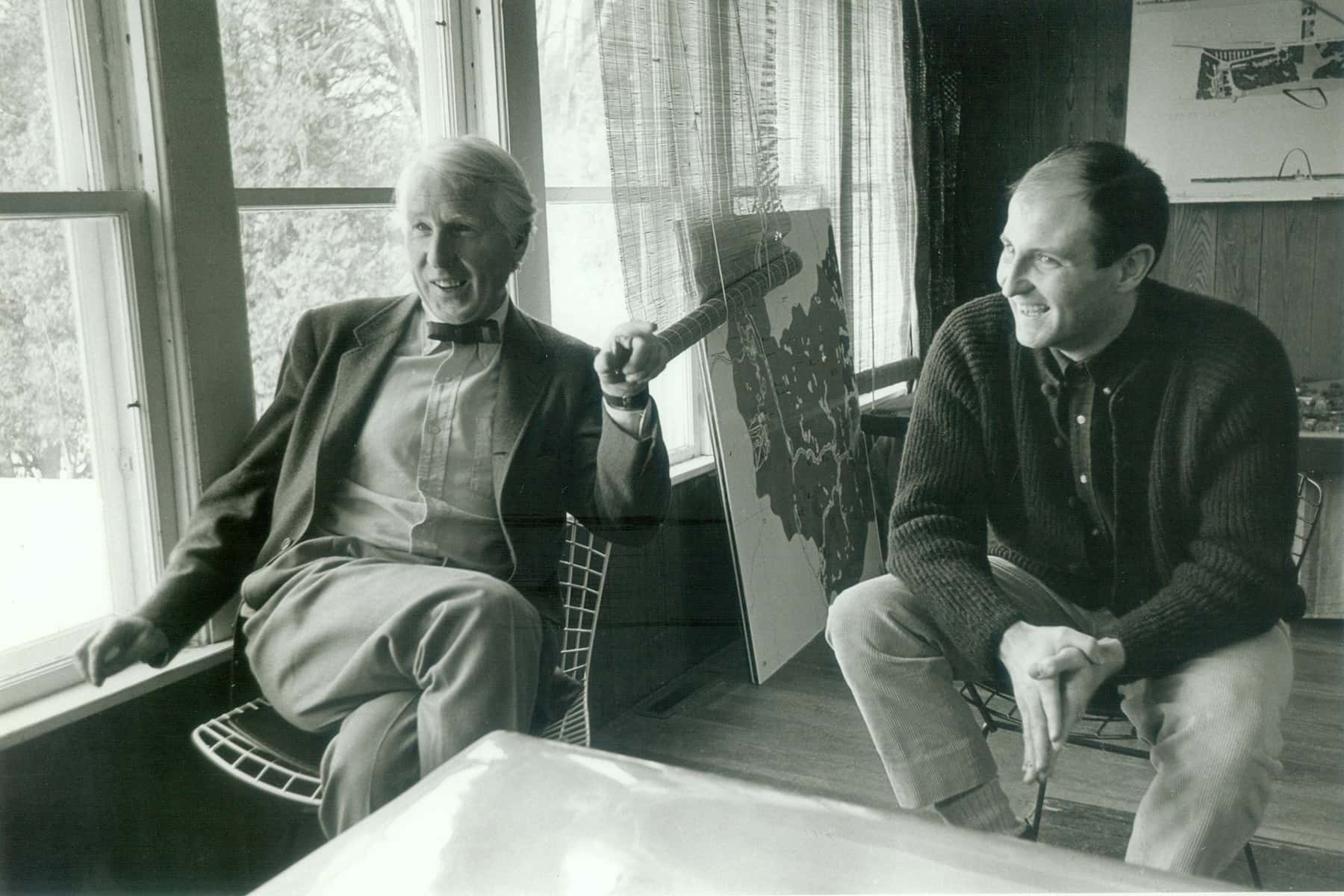

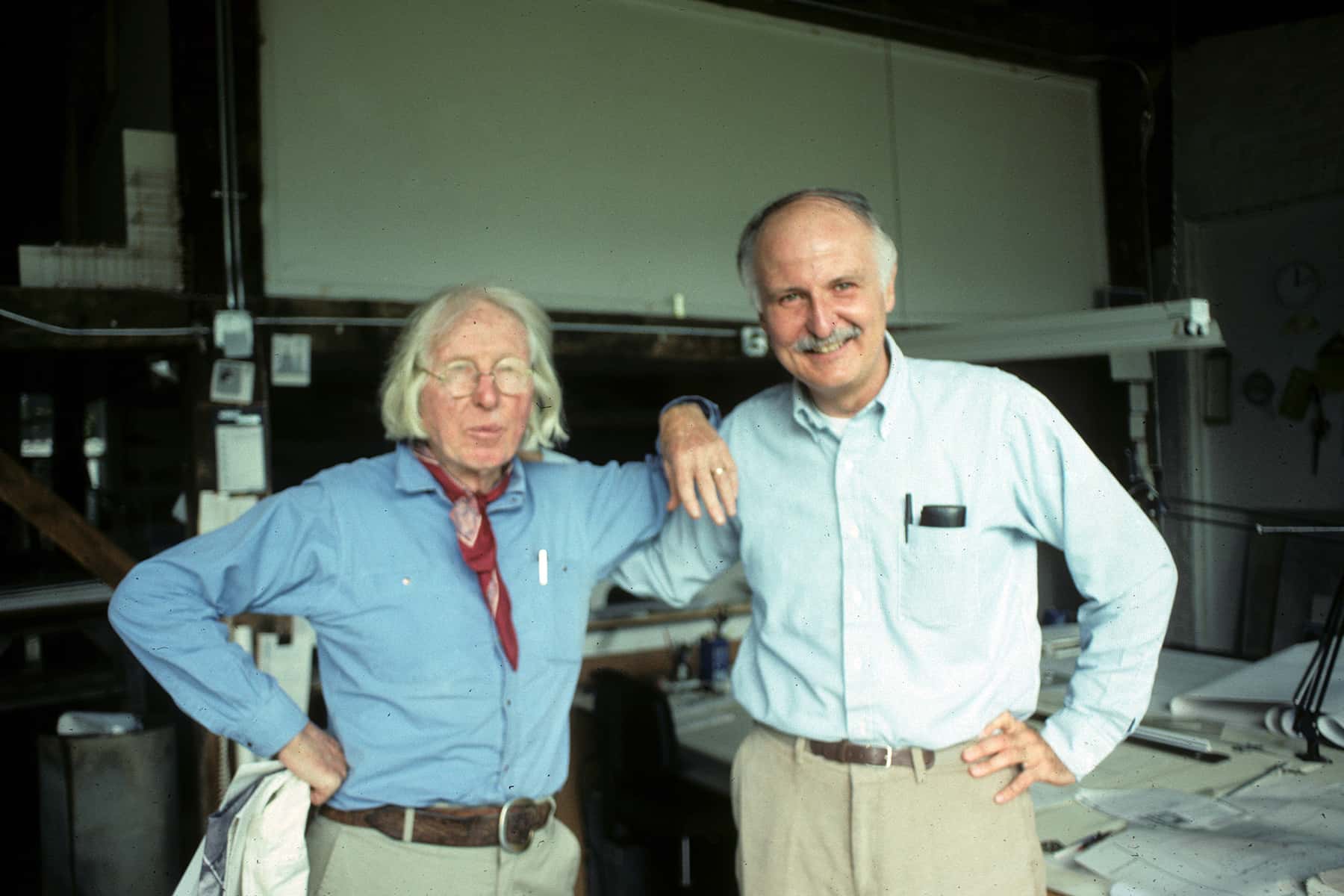

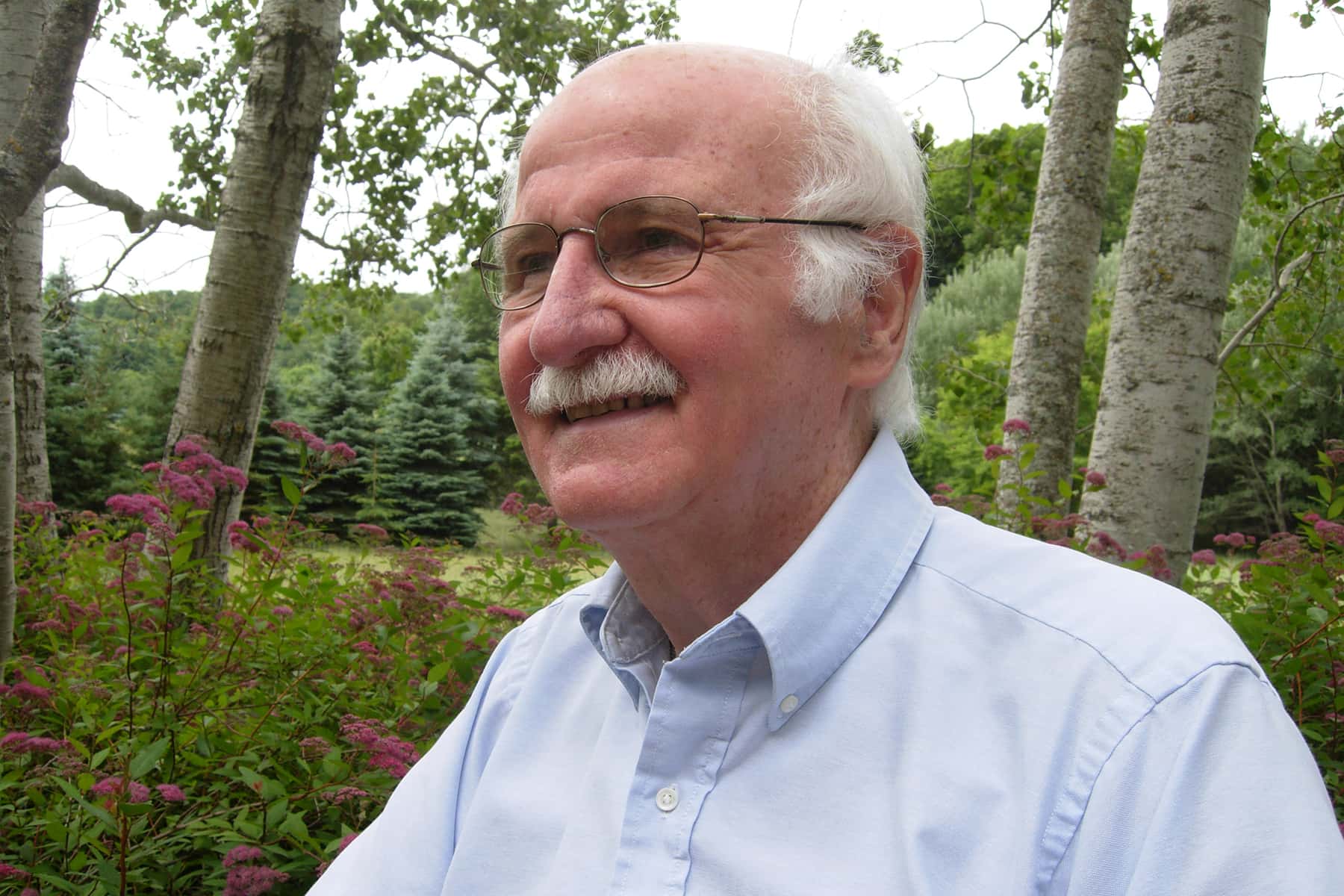

According to Joe Karr, a retired landscape architect and former associate of Weese and Kiley, big-picture thinking was second nature to the close collaborators who were both acclaimed masters in their fields.

BRIDGING PAST AND FUTURE

A half century ago, Harry Weese doggedly advocated for Chicago to retain its architectural gems. Now the Windy City is consistently ranked as America’s top city for both historic and contemporary architecture. He was known in his hometown as the “conscience of Chicago,” and remembered as the architect who “shaped Chicago’s skyline and the way the city thought about everything from the lakefront to its treasure-trove of historical buildings,” according to Blair Kamin’s “Chicago Tribune” obituary in 1998.

As the growing city moved full tilt into the future, Weese urged also preserving the past. Navy Pier, now the most-visited destination in the Midwest, was among sites Weese helped get listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Weese’s firm restored Chicago’s venerable Auditorium Building, designed by Dankman Adler and Louis Sullivan; and Daniel Burnham’s Orchestra Hall and Field Museum of Natural History. An eclectic Modernist, Weese also designed Chicago’s soaring Time & Life Building and the acclaimed circular Seventeenth Church of Christ, Scientist, among many commissions there and worldwide.

Harry Weese was chosen in 1967 to design the 100-mile Washington DC Metro system. New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp wrote in an obit, “Given the opportunity to work as an equal partner with the project’s engineers, Mr. Weese designed a system-wide network of stations that rank among the greatest public works of this century.” Muschamp wrote that some of the vaulted-ceilinged stations “induce an almost religious sense of awe.” Weese went on to become the foremost designer of transit systems at the peak of his career, also overseeing rail projects in Buffalo, Dallas, Los Angeles, and Miami, and the restoration of Union Station in DC.

THE WALL THAT HEALS

In 1981 Weese served on the selection committee for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the Washington Mall, and is credited with advocating for the stunning design created by Maya Lin. A World War II Navy veteran, he quickly recognized the potential of the 21-year-old architecture student’s proposal among 1,420 entries, and helped the design survive considerable opposition. Weese arranged for a scale model of the black-granite wall etched with names of fallen veterans, to help decision makers and others visualize the nontraditional design. The memorial quickly became a profound space for public grieving and healing and was recently featured in the PBS documentary “10 Monuments that Changed America.”

MAKING CITIES BEAUTIFULLY LIVABLE

An ardent urbanist, Weese wanted cities to be so beautiful and welcoming that people would choose to live in them – rather than flee to the suburbs, a trend in full swing as his career took off in the 1950s. Weese’s holistic city-planning visions were nurtured in Cranbrook Academy of Art’s multi-disciplinary graduate program. Architect Eliel Saarinen, then dean, encouraged all students to learn sculpture, weaving and other arts. Weese’s later-renowned classmates included Benjamin Baldwin, Harry Bertoia, Charles and Ray Eames, Florence Knoll and Eero Saarinen. A frequent collaborator of Dan Kiley, Saarinen designed the War Memorial on Milwaukee’s lakefront.

Karr said that as a young architect Weese “was interested in Mies Van der Rohe, like almost everyone else of his generation. But his true mentor was the great Finnish architect and designer Alvar Aalto, with whom he studied architecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Harry travelled to Finland to see Aalto’s work. The feeling of Aalto appears in much of his work – in some of the spaces formed, the window designs, and materials used, such as brick and wood inside buildings.” Aalto was noted for being a “humanist Modernist.”

Visionaries are always in demand, even long after they are gone. And embracing the legacies of a city’s shapers offers both bragging rights and opportunities for education and economic benefit. It’s not to extol exceptional creators of places—but rather so that ongoing generations can learn from influential projects and the narratives underlying them. Visiting spaces that retain their defining characteristics provides the most direct access to a city’s unique stories.

Milwaukee’s historic preservation planning staff say the Marcus Center’s nomination meets four criteria for preservation: The site exemplifies the development of the cultural, economic, social or historic heritage of the City of Milwaukee; is the work of an artist, architect, craftsperson or master builder whose individual works have influenced the city’s development; is a unique and iconic location within the city; and embodies distinguishing characteristics of an architectural type or specimen.

As City of Milwaukee officials deliberate whether to grant the Marcus Center permanent historic designation, they will weigh in on more than a monumental building, an elegant plaza, and what some consider a magical grove. Officials must decide whether the Marcus Center has historic value and is a place worth keeping and stewarding so that it retains that character.

THE PUBLIC REALM AND A SENSE OF PLACE

Preservation of well-designed public spaces can allow people to experience a recognizable sense of place. Honoring the work of masters like Harry Weese, Dan Kiley, Eero Saarinen and others protects a city’s collective inheritance. Attaching value to Milwaukee’s public-space built heritage can also drive tourism and enhance real-estate values, as it has done in Chicago, Boston and other cities.

Peter McAvoy, a longtime local civic leader, also sees potential for the Milwaukee community to “use this opportunity to consider how the Marcus Center and nearby downtown areas can be part of a broader civic vision.” As the former head of environmental health at Sixteenth Street Community Health Center, McAvoy helped facilitate a collaborative visioning process that led to Menomonee Valley’s revitalization. Such a process could reinvigorate the Weese-Kiley plan, which followed years of civic discussions about the location and purpose of the PAC.

After a lengthy public hearing on April 1, the City of Milwaukee’s Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) voted in favor of granting permanent historic designation to the Marcus Center. The HPC also approved a Certificate of Appropriateness for four trees identified as potential safety hazards to be cut down, with the requirement that they be replaced in kind within a year. Commissioners stressed that it is essential for the Marcus Center’s stewards to develop a plan to maintain and preserve what the HPC considers a culturally and historically significant asset. The designation issue must also be heard by the Common Council’s Zoning, Neighborhoods and Development (ZND) Committee. HPC staff said that the earliest the ZND Committee could hear it will be April 30. Then the full council will vote whether or not to approve designation.

Celebrating Harry Weese’s big-picture thinking, and the wide-ranging and ambitious projects he designed here and elsewhere, could well inspire a new era of respect for Milwaukee’s historic uniqueness and optimism about our future promise.

Virginia Small

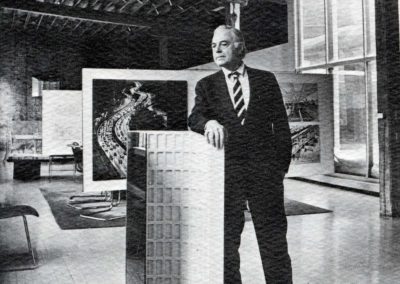

Joe Karr and Harry Weese & Associates