This column is part of the special series From Mississippi to Milwaukee: My Journey to 53206 by Reggie Jackson, that explores the 53206 zip code of Milwaukee in an effort to educate about the historical context and social process that drove the once thriving part of the city into its current problematic condition.

“The fight has just begun.” – Thurgood Marshall after winning Brown v. Board of Education case

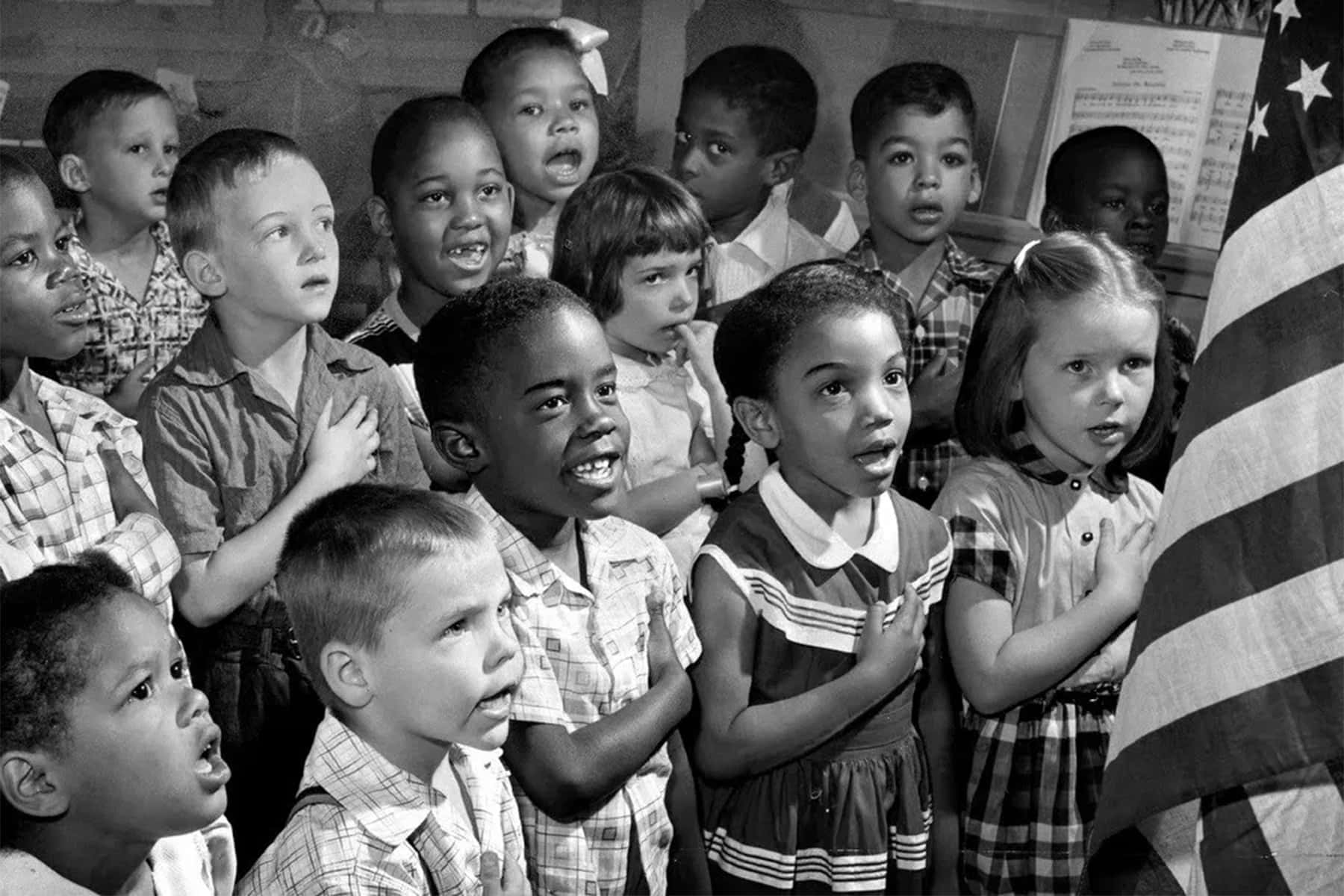

On May 17, 1954 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. The work of decades of litigation by the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) put in motion the end of the reign of legally mandated segregation demanded by the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision.

As a little boy growing up in Mississippi, I was too young to understand anything about that Supreme Court ruling, other such legal cases, or even the idea of segregated schools. I did not know it at the time, but when I started first grade the state of Mississippi had just integrated its schools.

They were one of many states that fought the Brown v. Board of Education decision by refusing to open their schools to every student regardless of race. Every member of my family in Mississippi had attended all-black schools prior to 1970. The school I attended that first year had previously been the all-white school in town.

I began my education in Mississippi in an integrated school. Just before I started third grade we moved to Milwaukee. My first school was 20th Street School, on the southern edge of the 53206 zip code off of Meinicke Avenue and 20th Street. During third through fifth grades I lived two blocks away from school and had no white classmates that I can remember. We moved that summer and I switched to Keefe Avenue School for sixth grade. My middle school was called Parkman Middle School and was right across the playground from Keefe Avenue School. From sixth through eighth grades I had no white classmates.

My first white classmates since I left Mississippi would be in high school. I chose to go to Milwaukee Trade and Technical High School (Milwaukee Tech) on the south side of Milwaukee. I did not notice the schools in Milwaukee being segregated because all of the neighbors I remember having – with few exceptions – were black.

How ironic that the state so many people consider to have been the epitome of segregation – Mississippi – was the place where I had white classmates. While Milwaukee, the big city “up North” in Wisconsin that we moved to, had schools where I was without white classmates for six years.

The Brown court decision has been celebrated as a landmark in the history of Civil Rights. The 60th anniversary of the decision was celebrated with great fanfare in 2014. Like so many other landmarks in United States history, most Americans know much less about the decision than they should.

Oliver Brown filed a class-action lawsuit against the board of education of Tоpеkа, Kаnsаs in 1951 because his daughter Linda was denied admission into the all-white Sumner elementary school. Several other black families joined the lawsuit with the Brown family when their children were denied access to all-white schools as well.

The brilliant attorney Charles Hamilton Houston, the Dean of Howard University Law School and Special Counsel of the NAACP, and his team – which included his protégé Thurgood Marshall and Oliver W. Hill – would combine the Kаnsаs case with similar lawsuits in Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington DC.

After years of struggle in lower courts, Houston argued the case before the U.S. Supreme Court. The effort to challenge segregated schools began in the 1930s. They commissioned a study by Nathan Marigold, which found “that under segregation, the facilities provided for blacks were always separate, but never equal to those maintained for whites.” He made a point of challenging the separate schools as a violation of the equality aspect of Plessy’s “separate but equal” principle.

The NAACP began developing a strategy and course of action following the leadership of Houston.

“Under Houston’s “equalization strategy,” lawsuits were filed demanding that the facilities provided for black students be made equal to those available to white students, carefully stopping short of a direct challenge to Plessy. Houston predicted that the states that practiced segregation could not afford to maintain black schools that were actually equal to those reserved for whites.” – NAACP

Thurgood Marshall would succeed Houston as NAACP Special Counsel and argued the case before the Supreme Court. The court ruled that segregation in public education violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court agreed with the NAACP that public school segregation had a “detrimental effect upon the colored children.” The court stated that “a sense of inferiority” was created in black students by being in the separate schools. However, the ruling did nothing to provide an immediate remedy.

“In the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” – Brown Brown v. Board of Education Decision

The second phase of the case came the following year with much less fanfare. In Brown v. Board II the court remanded all future desegregation cases to the lower federal courts. Using language that still haunts us, the court ordered district courts and school districts across the country to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.”

The backlash was immediate. By giving the implementation to local officials the court created an opportunity for whites to evade the ruling. In Arkansas, Governor Orval Faubus called out the National Guard to prevent black students from entering Little Rock’s Central High School. President Eisenhower would be forced to deploy federal troops to escort and protect the first nine black students, known as the Little Rock Nine.

Virginia adopted a policy called Massive Resistance to fight the Brown decision in 1956. U.S. Senator Harry Byrd Jr. led the effort to block the integration of the schools. Public schools were shut down in Front Royal in Warren County, Charlottesville, and Norfolk. Federal courts forced them to reopen. Whites formed a political pressure group called Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties, to preserve racial segregation. Governor Thomas B. Stanley put together a commission led by Garland Gray to fight implementation of the ruling.

“Appearing in November 1955, the Gray Plan proposed selective repeal of the compulsory school attendance law, establishment of pupil placement criteria, and provision of state tuition grants to students leaving desegregated schools to attend private segregated ones.” – Encyclopedia Virginia

In August 1956, Virginia developed the Stanley Plan by creating a state Pupil Placement Board to block assignment of black students to white schools. It also put in place rules to close schools in the state. In September 1959, Prince Edward County closed all of its public schools to prevent integration. They would remain closed for five years until reopened by the courts. White students were taught in “private academies” using state education funding to pay their tuition while black students were denied access to formal education for the entire five years.

In Milwaukee, the public schools were largely segregated as well. The district argued that there were no legal mandates for separate schools in the city. This de facto segregation – segregation by fact – was in contrast to the de jure segregation – segregation by law – in the South. Neighborhood schools in Milwaukee were largely segregated because of the policies that denied blacks the ability to live outside of their neighborhoods. The boundaries of where blacks lived in 1960 were Capitol Drive to the north, Juneau Avenue to the south, Holton Street to the east and 27th Street to the west.

Four years prior to the Brown decision the black population in Milwaukee was 8,821. There were 70,505 students in Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS). The 4,568 non-white students accounted for just 6.6% of the students in the district. By 1960 there were 101,504 students in the district and 81,270 of them were white (80.1%). As the black population continued to grow in Milwaukee, whites left the city in large numbers. In 1965 the district had 121,904 students. Non-white students numbered 27,939, which was just under 23% of the district.

The district used a policy known as “intact busing” to ease segregation. Black students and their teachers were bused to schools on the south side and kept completely separate from their white peers. They were forced into the basement or other unused place in the schools or in some instances a mobile trailer was placed on the playground for their classrooms. Some black students were bused back to their neighborhood schools to have lunch before taking the bus back to the south side school to finish the day.

As the student populations grew very rapidly in the 1950s and 1960s, the school board built new school buildings. However, the new schools were constructed on the south side where the student population was dropping. On the north side, where the student population increased by more than 50,000 students from 1950 to 1965, the district only added rooms to those overcrowded schools. The staff was not diverse in the district either. There were only 442 black teachers in MPS during 1965, out of the 4,331 teachers employed by the district. Of the principals and assistant principals in the district that year, 236 of the 238 were white.

Attorney Lloyd Barbee moved to Milwaukee in 1962. He immediately led fellow NAACP members and black families to challenge the condition of the schools in the city. The district had intentionally put very strict neighborhood boundaries in place to maintain segregated schools. They would redraw the boundaries when too many blacks moved into white neighborhoods. Barbee and others threatened a boycott unless the district removed the boundaries, allowed students to choose their own schools and hired more black teachers by 1964.

Barbee helped form a group called M.U.S.I.C. (Milwaukee United School Integration Committee). Almost 12,000 MPS students participated in a series of boycotts in May 1964 to put pressure on the Milwaukee Board of School Directors. The students skipped going to MPS schools to attend class in over thirty “Freedom Schools” in black churches around the city. Whites opposed to integration petitioned the school board to uphold neighborhood schools and boundaries.

Due to frustration and a lack of progress on the demands to integrate the schools, Barbee filed a federal class-action lawsuit against the Board of School Directors on June 17, 1965. “Amos et al. v. Board of School Directors of the City of Milwaukee” filed on behalf of 41 black and white students, charged the Milwaukee School Board with unconstitutionally maintaining racial segregation in its schools. The case lingered in the federal courts until 1976. Finally on January 19, 1976 Federal Judge John Reynolds ruled that Milwaukee Public Schools were unlawfully segregated.

“Segregation exists in the Milwaukee public schools, and that this segregation was intentionally created and maintained by the defendants.” – Federal Judge John Reynolds

The district would fight the decision and appeal the ruling. The Supreme Court upheld the decision and in 1979 an agreement was reached. A consent decree was issued that forced the district to integrate the schools. This was the year I started high school and had my first white classmates in Milwaukee. The decision was not as impactful as many had hoped for.

By the time the case was finally settled, many whites had left Milwaukee. The white population in the city that peaked at 675,572 in 1960 (91 percent of population) dropped to only 453,970 by 1980 (71 percent of population). By 2010 whites were only 37 percent of the residents of Milwaukee, but just 13 percent of students currently in MPS are white.

Our schools are still highly segregated. Fifty-seven schools in the district have a student body that is 90 percent or more black, Latino, or Asian (49 black, 7 Latino, and 1 Asian). Only seven MPS schools have a white majority, and they are all elementary schools.

Despite the celebration of the landmark Brown decision, we are more segregated today than we were in the 1950s and 1960s. This does not mean black and Latino and Asian children can not receive a quality education in the district. Many do. Looking at the State Department of Public Instruction Annual School Report Cards shows that dozens of highly segregated, high poverty schools in MPS are meeting and often exceeding expectations.

The issues we face are based more on funding or a lack thereof. We still fund Milwaukee schools based on property taxes. Because of depressed property values in the city and massive cuts to the education budget under former Governor Scott Walker, our children are being devalued and cheated out of the resources they need.

Our schools used to be effective and had high graduation rates before de-industrialization and the massive loss of manufacturing jobs, which was accelerated by the recessions of the early 1980s. Poor communities, stuck in poverty due to high unemployment and low wages, plague our city and contribute to our poor school performance.

If we are serious about making Milwaukee a better place to live, we should do something significant to fix our economy, and fund our schools differently than we currently do.

“Education is the passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to those who prepare for it today.” – Malcolm X

© Photo

Richard Stacks via Library of Congress

- My journey from integrated schools in Mississippi to segregated schools in Milwaukee

- The impact of deindustrialization on Milwaukee’s Inner City

- When the jobs went away crime followed

- The growth of mass incarceration in Milwaukee

- Remembering a time when 53206 was known as a loving community to grow up in