Black Americans did not abandon liberal democracy because of slavery, Jim Crow, and the systematic destruction of whatever wealth they managed to accumulate; instead they took up arms in two world wars to defend it. Japanese Americans did not reject liberal democracy because of internment or the racist humiliation of Asian exclusion; they risked life and limb to preserve it. Latinos did not abandon liberal democracy because of “Operation Wetback,” or Proposition 187, or because of a man who won a presidential election on the strength of his hostility toward Latino immigrants. Gay, lesbian, and trans Americans did not abandon liberal democracy over decades of discrimination and abandonment in the face of an epidemic. This is, in part, because doing so would be tantamount to giving the state permission to destroy them, a thought so foreign to these defenders of the supposedly endangered religious right that the possibility has not even occurred to them. But it is also because of a peculiar irony of American history: The American creed has no more devoted adherents than those who have been historically denied its promises, and no more fair-weather friends than those who have taken them for granted.

– Adam Serwer, The Atlantic’s “The Illiberal Right Throws a Tantrum“

On a day that those in the African American community celebrate the end of our official enslavement, we must reflect on the current state of affairs in the United States. Just as has always been the case, the argument about America as the land of freedom, justice, and liberty for all is in question by marginalized communities.

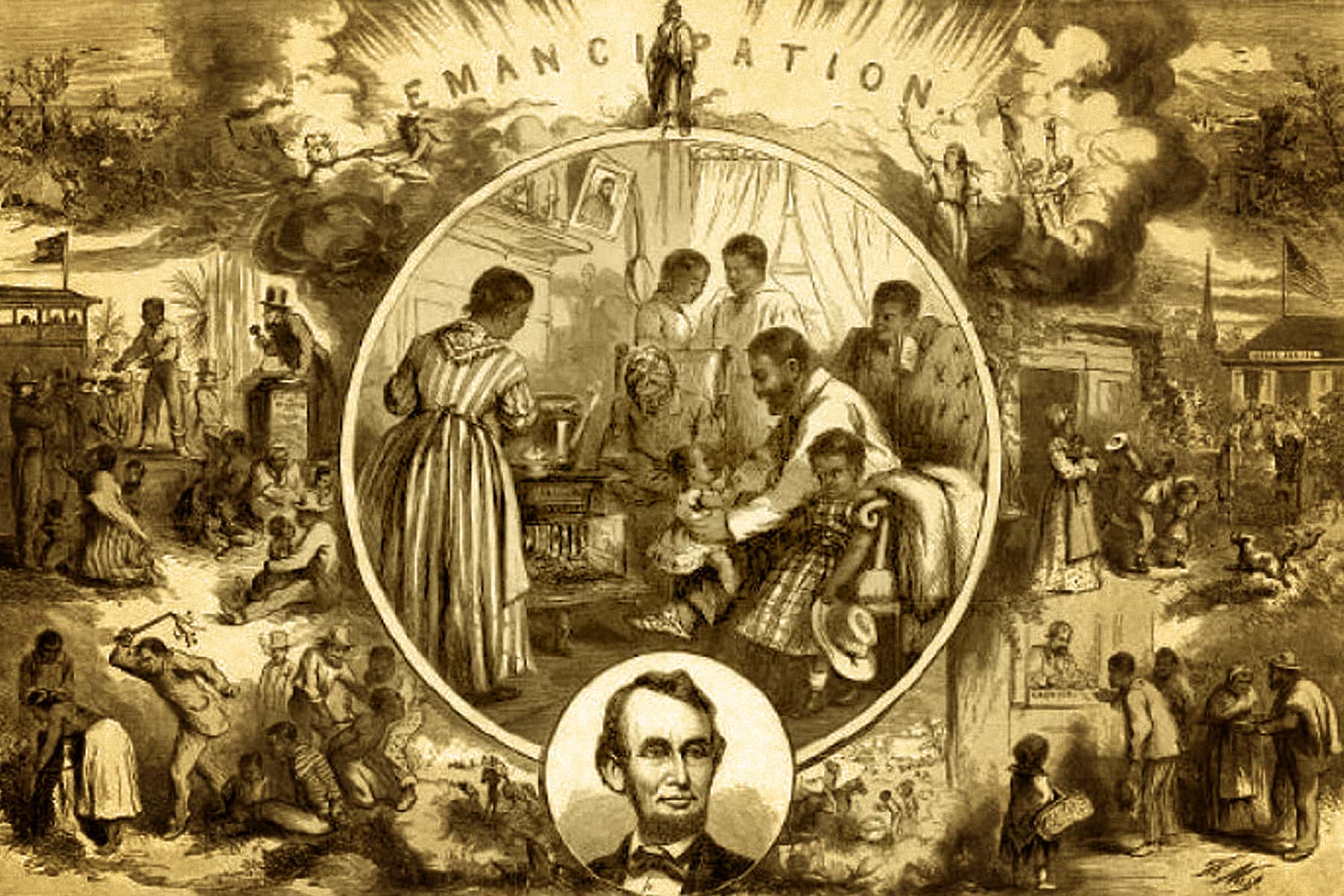

Juneteenth is the traditional holiday of June 19th that we observe as the end of slavery. On June 19, 1865 the last group of enslaved Africans in Galveston, Texas were notified of the Emancipation Proclamation issued by Abraham Lincoln – two and a half years earlier. For decades within the community of the formerly enslaved, it was the largest holiday of the year in many respects, celebrating freedom that was denied for two hundred and forty six years.

This August will mark the four hundredth anniversary of the first kidnapped Africans arriving in the British colonies of America. Two hundred forty six years of enslavement followed by over one hundred years of American Apartheid, Jim Crow segregation, lynchings, and mob violence. Devaluation in law and custom has been the American experience for most of us of African descent.

For Native Americans, the loss of their ancestral lands, genocide, enslavement, forced assimilation and devaluation and destitution has been their lived experience. For those who arrived from multiple places in Asia, exploitation, degradation, dehumanization, violence, and concentration camps has been their lived experience in America. For our Latino neighbors, exploitation, loss of ancestral lands, lynchings, marginalization, deportation, family separations, and false promises about citizenship are the memories of their time in America.

We love to espouse the ideals of the nation’s founders, but choose consistently and conveniently, just as the Founding Fathers did, to ignore these ideals. America has always kept walls of separation as a part of how it manages those it chooses as undesirable. Early on in the colonies, these separations were based on gender and religion. Over the course of time the boundaries have been extended to include a larger number of those Jefferson spoke about in the Declaration of Independence.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government…” – The Declaration of Independence

The words that have always stood out to me from the Declaration of Independence, is “consent of the governed.” Some of the British colonists had complained about the King of England refusing to listen to their voices and govern based on their needs. For too long, these same concerns have been expressed by many of us. Our leaders have routinely ignored these voices. More problematically, American leaders have promoted and codified into law the establishment of marginalization and oppression of many.

About one-half of the Founding Fathers of this country were slaveholders. Many others directly benefitted from businesses that supported and profited from the institution of slavery. Colonial leaders who preceded them insured that the original inhabitants of the land would not just lose the land that they called home, but brutally took that land, killing massive numbers of men, women, and children in the process.

These are aspects of the story of America that are either left out of or barely touched upon by the history textbooks and classes we all were exposed to. None of us received a real story of American history in school, nor do our children get one today. As a result, we do not understand how we became who we are as a nation. We customarily leave most of the bad stuff that we have done as a nation out of our history classes, while celebrating the positives. The real story is much more nuanced and ugly.

How can we expect to overcome our continual attempts to marginalize and dismiss groups we have deemed undesirable? By being honest with ourselves. We have never done it in any appreciable way. It is time we do.

We have a beautiful monument to America that stands in New York City. The Statue of Liberty is supposed to be the symbol of our openness. We tell the world that we accept “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

That golden door has never been open to all. We are currently and in many ways miraculously, the most diverse nation on earth. I say miraculously because, we have practiced what I call an “aversion to diversity” throughout American history. We have always pushed some away while welcoming others. Even when we accept different groups, the country has marginalized them once they had arrived. Irish immigrants were called “monkeys” and treated as second-class citizens. We called Italian immigrants “natural born criminals” and forced Latin Americans, Filipinos, Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, and other Asians to work as semi-slaves.

We erected barriers to citizenship in 1791 by decrying only whites could be citizens. America debased those it did not want as immigrants by passing strict laws, which disallowed their legal immigration. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was the only American law to specifically ban an entire nation of people from legally immigrating to this country. In 1917 the Asiatic Barred Zone Act denied many other Asians the right to come to America. In 1924, under fierce pressure to appease the Nativist passion spreading across the country, we passed the strictest immigration law in U.S. history, the Johnson–Reed Act.

This federal law included an extension of bans on Asian immigration in the Asian Exclusion Act. Another provision excluded from entry any alien who by virtue of race or nationality was ineligible for citizenship. Even Asians like the Japanese who had previously been admitted to the United States were then banned from coming. In 1920, Vermont Senator William P. Dillingham introduced immigration quotas, set at three percent of the total population of the foreign-born of each nationality in the United States, as recorded in the 1910 census. This allowed only 350,000 visas to be issued to new immigrants. After President Wilson used a pocket veto to kill the idea in 1920, President Warren Harding in 1921 called a special session of Congress to pass it. In 1922 Congress extended it for two more years. In 1924, the year of the census used for the quotas was pushed back to 1890. Before many of the Southern and Eastern Europeans came, it was designed to keep out those groups who had previously arrived in large numbers. The quota was also lowered to two percent.

This is just a small piece of the story of America. There are so many more challenges we face that are directly related to the past. We continue using the same methods and motivations to keep people out, and to marginalize those that are here already. Yet we say all those things, like slavery, happened so long ago and that those people – the marginalized – should get over it.

Juneteenth is a bittersweet celebration for me, because I know these words of the Thirteenth Amendment allowed slavery to continue in a new form.

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Slavery did not end for those in Galveston, Texas who received word of their freedom on June 19, 1865. A new system came about as a result of the language used in the amendment. The Convict Lease system allowed innocent boys and men, most of them black, to be enslaved and sold to the work farms for free until the federal government in the 1930s finally ended the practice.

In many ways, the mindset of Americans that supported and maintained the enslavement of millions of Africans, as well as the marginalization of Native Americans and others, continues to exist today. The hearts and minds of our nation need to change. Public pressure by those of goodwill is simply not enough.

Our history tells us that we need to do more. We need to not just do more, we need to advocate in a more forceful way than we ever have before. We are overdue for living up to the lofty ideals of the Founding Fathers. What is different now is that we need to ensure all people are included in these promises. No exclusions this time, America.

© Photo

Library of Congress