This special series by Reggie Jackson explores his journey across four cities in Alabama, to visit historical sites that many are trying to erase from public memory so the disturbing truth about racism, segregation, and White Supremacy can be forgotten. mkeind.com/alabamajourney

As I said in yesterday’s column, Tuskegee was a place I was not sure we’d have time to see on out trip. I had mostly written it off as a place to see because of our tight itinerary. I’m glad we stopped there though.

Tuskegee is a very small town in the heart of Macon County, Alabama, famous for the esteemed Tuskegee Institute (University) created by Booker T. Washington, and also the home of the Tuskegee Airmen, but just as well known for the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

Driving on the highway to Atlanta, we exited after seeing a sign pointing towards Tuskegee Institute and another pointing to the home of the Tuskegee Airmen.

We drove into town to see Tuskegee Institute first. We had heard from the man we met in Birmingham who we saw again in Montgomery that it was closed up. We went anyway.

As we drove up to the Southeast gate it was closed and locked. It was the home of the Tuskegee Veterinary Teaching Hospital and School of Veterinary Medicine.

A little further down the road was the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Hospital, founded in 1923. It was the first, and for decades, the only veterans hospital in the country administered by an all-black staff. The segregated hospitals in the South, included these hospitals for veterans. The second president of Tuskegee University, Robert. R. Moten and other Black leaders convinced President Calvin Coolidge to provide a hospital for Black WWI veterans. It would be decades before these veterans hospitals would be integrated.

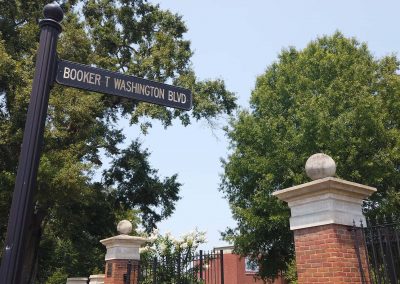

We backtracked around town and found the main campus of Tuskegee University. Tuskegee was founded in 1881 by Booker T. Washington. As one of the leaders of the Black community at that time, Washington wanted to create a place where Blacks could learn the skills that would provide them expertise in the so-called “negro jobs.” He felt very strongly that the White power structure would continue to keep Blacks out of most professions and wanted Blacks to excel and become self sufficient.

His views were in contrast to those of W.E.B. DuBois, a Black leader who criticized Washington for appeasing the White power structure and accepting segregation instead of challenging it. The two men would fight in their own ways to move the Black community forward over decades.

On the campus is the home Washington built for himself and his family. It was surreal to be standing in front of the home of a man that I was star struck by as a young boy. At that time, he was considered the second most important Black leader in the country’s history, behind only Dr. King. At least that’s what I remember the schools and encyclopedias telling me.

Tuskegee would become one of over one hundred historically black colleges and universities (HBCU’s) built across the country. The first was Cheyney University in Pennsylvania, created in 1837. Later in 1856, the first of these HBCU’s to be run by Blacks, Wilberforce University in Ohio, opened its doors. In December 1865 shortly before the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery, Shaw University in North Carolina became the first southern HBCU.

There are currently just over 100 HBCU’s still in existence and they have played a critical role in the education of Blacks in this country. HBCU First documents the history and importance of these educational institutions.

“From the late 1800s to the late 1900s, HBCUs thrived and provided refuge from laws and public policy that prohibited Black Americans from attending most colleges and universities.

HBCUs provided undergraduate training for 75% of all Black Americans holding a doctorate degree; 75% of all Black officers in the armed forces; and 80% of all Black federal judges…Before higher education was desegregated in the 1950s and 60s, almost all Black college students enrolled at HBCUs. Legal segregation had prevented Black Americans from attending college in the South, and quotas limited the number of Black students that could attend college in the North.”

Tuskegee became one of these important places and continues this long tradition. One of my favorite sites on the journey was the sign at Tuskegee that said “Frederick Douglas Gate and Lane.”

We left the University and traveled back toward the Tuskegee Airmen Museum on the edge of Tuskegee. It is at the Moon Field Municipal Airport, named after the aforementioned Robert R. Moten. The sign outside introduces you to the “Home of the Tuskegee Airmen.”

As WWII raged in Europe and the Pacific, the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor pulled the U.S. into the war. The Army Air Corps (AAC) quickly realized it needed trained pilots and contracted with private flight schools to fill the need. Tuskegee was selected as the sole flight training school for Black pilots. Tuskegee’s President Dr. Frederick D. Patterson along with George L. Washington, Director of the Department of Mechanical Industries pushed to get the designation for Tuskegee.

Over 1,000 airmen trained at Tuskegee and later gained the moniker the Tuskegee Airmen. They were placed into segregated units in the war. The first of these was the 99th Pursuit Squadron, later renamed the 99th Fighter Squadron. It would be followed by the 100th, 301st, and 302nd Fighter groups, the 616th, 617th, 618th and 619th Bombardment Squadrons were part of the segregated 477th Bombardment group.

Alabama was a highly segregated state and just getting to Tuskegee by train was a fraught journey for these men who would become heroes during the war.

“One thing that comes to mind is the difficulty many of us encountered in traveling by train to Tuskegee. We were required to ride in Jim Crow cars and to eat in a segregated section, behind a curtain.” – Judge John W. Rogers Sr.

Despite this treatment, the Tuskegee Airmen distinguished themselves during the war, bringing a great deal of pride to the Black community, and leading a strong push to demand better treatment back home after helping to win the war abroad.

We walked through one of the original hangers they trained in and got a sense of the heroism of these proud men.

While in Tuskegee, one thought stayed in the back of my mind. The infamous Tuskegee Syphilis experiment took place there for forty years. In 1932 ,the United States Public Health (UPHS), predecessor to the CDC, began the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.”

The study began with 600 Black men, 399 with syphilis, a debilitating sexually transmitted disease. Over the next four decades these men would be told they were being treated and given medicine for “bad blood.” They received no treatment whatsoever even though penicillin came along and became the default treatment for syphilis.

A whistle-blower named Peter Buxton shared the story with a reporter and the story became front page news across the country. The Associated Press (AP) story exposed the inhumanity of the doctors, nurses and other researchers involved. These people watched the men being ravaged and eventually dying with untreated syphilis. The original author of the 1972 AP story, Jean Heller, wrote about this in a 2017 article.

“On July 25, 1972, Associated Press reporter Jean Heller broke news that rocked the American medical establishment. The federal government, she reported, had let hundreds of black men in rural Alabama go untreated for syphilis for 40 years for research purposes. A public outcry ensued, and the “Tuskegee Syphilis Study” ended three months later. The men filed a lawsuit that resulted in a $9 million settlement, and then-President Bill Clinton formally apologized years later.”

Despite the settlement, no one was ever held accountable for what happened to these men and their families. The names of all of those involved, with the exception of Black nurse Eunice Rivers who has taken almost all of the flack for the experiment over the course of time, have been left out of the retelling of the study.

Our journey of discovery ended on the road out of Tuskegee. I will explore my ending thoughts in the final article of this series, tomorrow.

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Birmingham, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Selma, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Montgomery, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Tuskegee, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: Final thoughts on my journey to visit Alabama and the history some want us all to forget