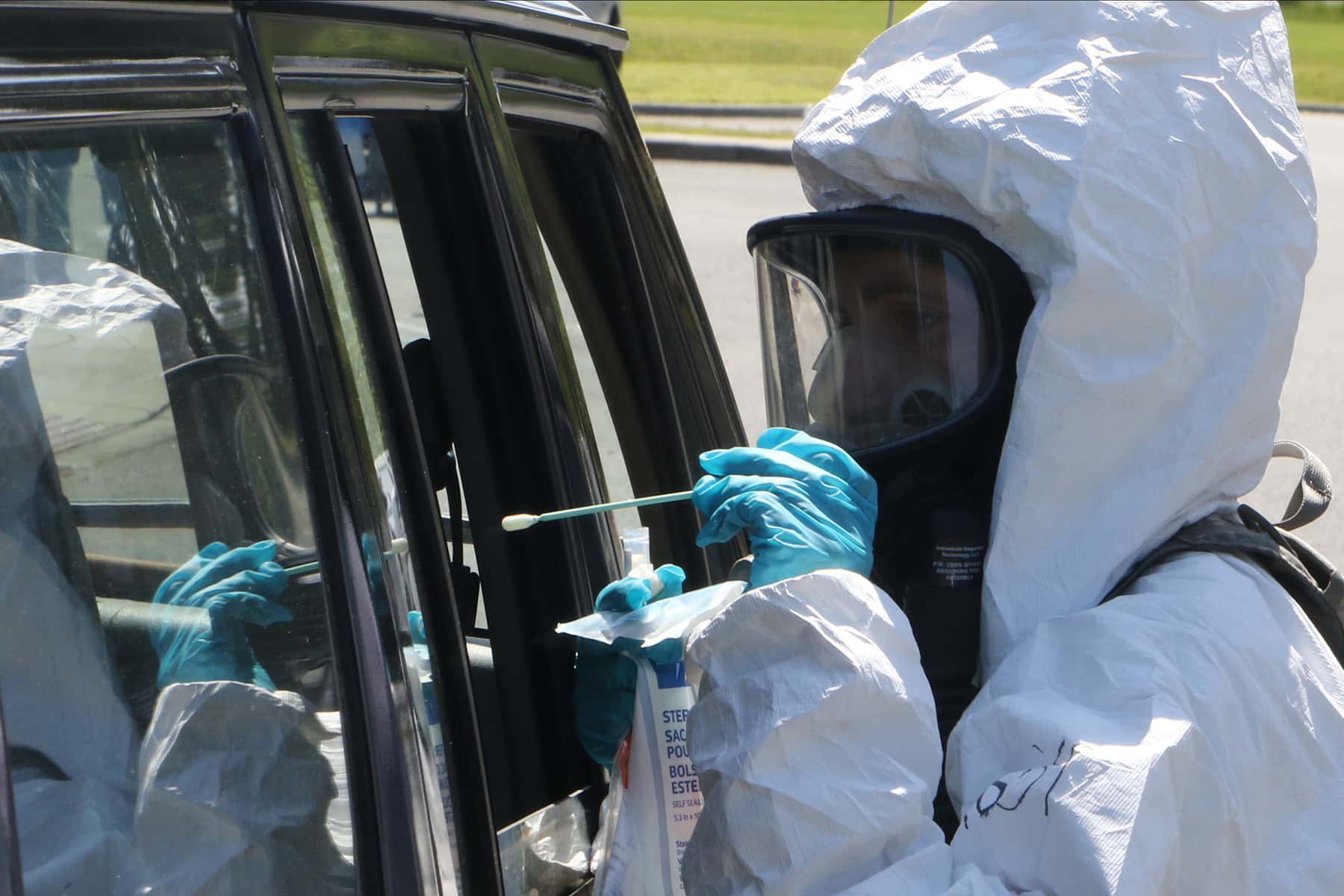

Wisconsin has bolstered its testing capacity during the pandemic, but not everyone is using it and challenges loom.

In the earliest days of the coronavirus pandemic, a shortage of testing supplies and staff at laboratories left Wisconsin and other states struggling to quickly identify infections and isolate contagious people. Four months after Governor Tony Evers declared the outbreak a public health emergency, the state has dramatically expanded its testing capacity.

But experts say too few Wisconsinites are showing up — potentially thwarting efforts to neutralize a virus that killed at least 831 people in the state as of July 16.

Wisconsin has 83 labs that can perform more than 24,000 total tests each day, according to data that public, private and commercial labs voluntarily report to the state Department of Health Services. That’s about 7-times the capacity reported on April 1. Twenty-four additional labs are “planning to test.”

But Wisconsin typically uses less than half of its reported capacity. DHS reports a 7-day average of roughly 11,700 test results per day, although that number hovered around 14,000 on July 14, 15, and 16.

Even Wisconsin’s June 3 record of 16,933 test results sits below the 19,000 needed to pursue a strategy to prevent spreading — or the 70,000 needed to suppress the outbreak, according to a Harvard Global Health Institute analysis conducted last month. Wisconsin was among 32 states falling short of the mitigation criteria, according to the study.

DHS officials urge testing for people who have COVID-19 symptoms — including a cough, shortness of breath, fever and chills — or suspect they were exposed to the virus. Testing is likely lagging because many prime candidates still aren’t showing up, said Ajay Sethi, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and director of its Master of Public Health program.

“The only way you will know whether or not that you have COVID is to get a test,” he said. “It’s very important to make sure that when somebody recognizes that they’re indicated for a test, they need to go get a test.”

Calls for more participation come as known virus cases are surging across the state and country. Wisconsin set daily records for confirmed cases four times since July 9, nearing 1,000 cases on some days, DHS data shows.

“These numbers are not the result of more testing,” DHS Secretary Andrea Palm said on July 14 during a media call. “These numbers are the result of significant community spread here in Wisconsin.”

Chuck Warzecha, deputy administrator of DHS’s Division of Public Health, called testing volume a key piece of a complicated puzzle. Harvard’s recommendations are useful for mapping out capacity needs as the crisis persists, Warzecha said, but conducting “the right testing” is even more important.

That means targeting high-risk populations, communities with active outbreaks and symptomatic people — along with their close contacts. The strategy includes scrutinizing nursing homes, where DHS has investigated 151 outbreaks of at least one coronavirus case. The Evers administration early in the pandemic also targeted testing outreach to African American, Latino and tribal populations.

“It would be great if everyone knew their infection status, and then we could all know when to stay home and not to expose others,” Warzecha said. “Without that, we just have to be a lot more strategic about how we use the testing that we have, so that we can find those most at risk, isolate the virus quickly and prevent the spread.”

Wisconsin may face additional challenges as the virus keeps spreading nationally — such as a shortage of testing materials. But states should not expect much help from President Donald Trump’s administration, which has played a hands-off role in responding to the pandemic, said Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, vice provost for global initiatives and chairman of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania.

“One of the problems of this whole national approach that affects everyone is the fact that it has been — each group is supposed to make its own decision,” he said.

Building testing capacity, experiencing hiccups

The Evers administration has promoted testing statewide, even deploying nearly 600 Wisconsin National Guard members to help collect specimens at certain sites. But officials cannot force anyone to get tested, and some people may be avoiding the experience because they misunderstand the virus’ risks, Sethi said.

“I think it’s important that we create an incentive and let people understand that if you are infected, testing is the only way to know whether that’s the case,” he said.

Wisconsin’s reported surplus capacity, if accurate, bucks a national trend, Emanuel said.

California, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana and Colorado have turned people away or even shuttered some overwhelmed testing sites. The main culprit for the problem: an overwhelmed supply chain for materials like nasal swabs and reagents — the chemicals needed to perform the tests. The supply crunch has meant long waits for results, hobbling efforts to trace contacts and isolate people who test positive.

Results become “literally worthless” if not reported within 10 days, Emanuel said. Wisconsin is not immune to regional testing hiccups, even with its reported capacity cushion.

Some test-seekers in Milwaukee and Madison reported hours-long waits, according to media reports. In Iron River, 142 test samples at a National Guard site were thrown away after being damaged while sitting in a hot vehicle. And some clinical labs could test more if not for a shortage of chemical reagents, Warzecha said.

The state resolved most early testing issues, Warzecha said, acknowledging the need for further improvements. One upgrade this month: an online registration tool at National Guard testing sites that aims to reduce wait times.

Could pool testing hold promise?

Wisconsin is evolving its strategies as some experts propose new ways to boost efficiency. Emanuel in mid-April joined Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Romer in calling for a 10-week national strategy to ramp up testing to millions per day. “It should leverage the thousands of research laboratories at U.S. universities, medical schools, and health-care systems,” the duo wrote for The Atlantic. (Nearly three months later, the United States is performing fewer than 800,000 daily tests, according to The Atlantic’s COVID Tracking Project.)

Emanuel and Romer also described pool testing — combining samples from several individuals and testing them together — as a “promising pathway” to speed processing and conserve supplies.

“If a pooled sample tests negative, everyone in the pool is negative. If it is positive, the members of the pool can be tested individually,” the experts wrote. Other researchers have touted the method’s potential.

Wisconsin has considered pooling tests, Warzecha said. The approach could prove effective in communities with lower virus rates, he noted. But pooling could waste time and supplies in COVID-19 hotspots, requiring more people to wait for a second test, he added.

In an interview on July 14, Emanuel called pooling “a way to squeak through” while the Trump administration offers little guidance or coordination to state and local public health leaders.

“A country like ours, we should be able to do other things,” Emanuel said. “We should have been spending the last four months beefing up the supply chain, making sure we had enough machines, inducing the large test companies to actually put in the capacity.”

Warzecha said his teammates are learning as much from state and local health departments as they are from the federal government.

“Everyone is doing the best that they can,” Warzecha added. “But more testing alone can’t thwart the virus. Other behaviors matter. If people are opening up too quickly, and people aren’t wearing masks when they’re in public, and they’re spending too much time in congregate settings, then it really isn’t going to be enough testing to help you stop the outbreak.”

Bram Sable-Smith

Wisconsin National Guard

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.