This article is part of a series that connects Milwaukee’s current social conditions with efforts in Alabama cities to publicly recognize their racial histories, to document the 1960’s Civil Rights Movement, and to extend and expand the Movement’s goals towards peace and reconciliation.

Monroeville is the birthplace of To Kill a Mockingbird, and the hometown of the novel’s author, Harper Lee. And its people and geography serve as the genetic makeup of “Macomb,” the fictional hometown of Scout, Jem, Dill, Calpurnia, Boo Radley and Atticus Finch. In some ways, the town itself is a character in this novel.

Monroeville rises from a rural Alabama crossroads; a red-ore tinted, dusty town with points of pride despite its appointments of poverty. The town is also an official destination on the Civil Rights Trail because of this novel’s themes and only because of this novel’s themes– of courage in the face of injustice and flawed judgments; of the fragility of a justice system that reflects the citizenry’s dark complicity with and dependence on racism; and of the overlay and interplay of poverty that not only underlies attitudes of resentment, fear, retaliation and hate but also spurs attitudes of generosity, kindness and hope.

Unlike other stops on the Civil Rights Trail, an historical civil rights event did not happen here; arguably only civil rights abuses are recorded in Monroeville. Indeed while the Chamber of Commerce promotes a biographical walking tour of Lee’s Monroeville, nothing from the fictional town of Macomb actually can be visited. Arguably the only true civil rights “site” the town offers is the Old County Courthouse.

Nevertheless, over 40,000 people per year make pilgrimage on the Civil Rights Trail to visit Monroeville and see the Macomb they have read about and to walk the streets that Atticus Finch might have walked. A significant number of those travelers, myself included, plan their visits during the annual month-long staging of the play version of To Kill a Mockingbird, staged and performed by the local townspeople since 1989.

THE ACTUAL MACOMB—MONROEVILLE, ALABAMA

Though renamed numerous times, the current town known as Monroeville is 200 years old. Because of its location, employment focused on grist mill work in its early days, followed by periods of prosperity focusing (in turn) on merchandising, small-farm agriculture and sharecropping, timber shipping and milling, apparel manufacturing, railroading, and pulp processing industries. Variously interests from the North exploited Monroeville’s people and industries, and caused fluctuations in the town’s periods of prosperity and periods of economic downturn. However, whatever prosperity Monroeville experienced, it never was shared equitably with the town’s black community.

From its beginnings, the Southern town was deliberately segregated along class lines but mostly along racial lines. In Harper Lee’s 1920’s childhood, she would have been surrounded by Jim Crow law culture, even though she likely would not have known personally its constricting effect on black citizens in her hometown. Throughout the novel she conjures and weaves the defined race and class lines demarcating permissible housing, employment, worship and commerce. Just as Lee portrayed in her revelations of Macomb’s Depression-era circumstances, the neighborhoods, schools, and business locations of Monroeville today reflect a quality of segregation about them that includes a sense of a town in economic straits, not yet emergent from its Great Recession circumstances.

Even with a declining population of only 7,000 residents, Monroeville is still the largest town between industrial Birmingham and the prosperous gulf town of Mobile. Just as when the railroads replaced the river transport to the west to create a Monroeville boon, so too the development of the Interstate to the east replaced Monroeville’s former prominence on the state’s byways, and replaced the critical need for Alabama 41 State Highway.

The three hour drive south on Old 41 is tree-lined most of the way, with occasional breaks in the forests exposing working farms that have seen better days. The sporadically paved crossroads are either haunted by ghost towns of abandoned villages, or are overwhelmed by competing signposts welcoming would-be congregants to an assortment of Christian churches— all unseen, behind the trees. Soon after leaving Birmingham, GPS ceases to function and cellphone bars fade; highway signs are sparse and fast food restaurants and gasoline stations are nonexistent on Old 41. Increasingly the trees lining the highway bear drapes of hanging Spanish moss, and the white rental car becomes an ersatz Pollack artwork– splattered with the red dust of the Southern clay soil. In totality, the drive down Old 41 creates a nostalgic atmosphere; a sense of driving back in time and space.

Old 41 bifurcates Monroeville. To the east is the “old downtown,” named as a National Register Historic District; to the west is the “urban sprawl” of big box stores, fast food eateries and other commercial outcroppings—with visibly high rates of vacancy or abandonment. Throughout Monroeville are residential plats, of various economic circumstances. In the center of the “old downtown” is a courthouse square on which sit both the Old County Courthouse and the “newest” County Courthouse (1963). Both are surrounded with blooming gardens; between them is a monument to Atticus Finch. The town does not boast with statues of Confederate heroes or city founders or even of James Monroe for whom the town is named. Instead its civic pride is expressed through a tribute to a fictional character – a white lawyer fighting for a black man wrongly accused—futilely challenging a compromised justice system.

The storefronts that circle courthouse square include some knickknack shops and resale shops, a restaurant, and a Speed Queen sales and repair shop. Also across from the courthouse square is the unrestored red bank building — the location of the former law office of both the real-life attorney A.C. Lee, and of the fictional Atticus Finch. The red bank building, as with many of the courthouse square’s ring of storefronts, is vacant.

The Old County Courthouse welcomed litigants from 1904 until its retirement in 1963. It was here that Harper Lee’s father and sister practiced law. It was here in the courtroom that movie studio set designers meticulously measured all aspects of its dark wood and white walls to recreate “the original” in Hollywood for the movie version of To Kill a Mockingbird. The Old Courthouse currently houses the Monroeville Area Chamber of Commerce and the Monroe County Heritage Museum. It includes a quaint gift shop, retrospectives of the County’s history and of its two most famous citizens – Truman Capote and Harper Lee– along with explanations about Monroeville’s self-styled designation as the “Literary Capital of Alabama.”

And for one month annually the Old Courthouse becomes the stage for the local folks’ production of To Kill a Mockingbird: the backyard becomes an open-air amphitheater for the first act and its courtroom serves as the stage for the second act.

THE STORY ORIGINS OF TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD

In 1960 Harper Lee wrote about the events in the “tired old town” of Macomb during the summer of 1934. The novel has two central plot lines. The first is a coming of age story about three children’s summer adventures and their fear of, but also fascination with, their reclusive neighbor “Boo” Radley. The second plot line is the trial of a black man wrongly accused of raping a white women. Both plot lines tell tales of injustices in a small Southern town. However it is the trial and its aftermath – and the towering, righteous attorney Atticus Finch–that has captured the hearts and minds of Lee’s millions of readers, movie goers and play watchers.

Lee published her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel at the burgeoning point of the Civil Rights Movement. Though couched in the 1930’s Depression era, the storylines reflect the racial tensions, viewpoints, fears and conflicts of the mid-century. It emerges at an historical moment when the civil rights movement in the South began to claim national news with disturbing headlines and broadcasts; when a nation, previously unaware of such pervasive racial abuses, was seeking to understand the origins and currency that fueled Jim Crow.

However, the novel also is influenced deeply by the racial injustice, culture and violence of Lee’s Monroeville childhood. Lee could not be left unaware of a major sensational trial in Monroeville when she was 10–of a black man who was unjustly accused of rape and sentenced to death. And she could not have been unaware of the racial violence in her hometown. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice includes 17 recorded lynchings/deaths of black citizens in Monroeville, the most recent occurring as late as 1943.

She knew that, prior to her birth, her father was appointed as counsel to defend two black men accused of murdering two white men. He could not obtain acquittals for his clients; they were convicted, hanged and mutilated. A.C. Lee never tried another criminal case. As though a piece of family lore, Harper Lee’s book recounts the personal courage of Atticus, and the risks to his family and himself and his law practice when he accepts judicial appointment as defense attorney for Tom Robinson, a black man unjustly charged with raping a white women.

THE PERSISTENT STORY OF TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD

With the Old County Courthouse restored, the town twenty-nine years ago began to perform the play version of Lee’s novel. The Mockingbird Foundation and its volunteers tend to all the logistics of TKAM—the shorthand reference which appears sporadically around town. For years Lee expressed displeasure at the public endeavor; she was a recluse from the world but was understood to be quite social among her fellow Monroevillians. So, in concession, the town fiercely protected her privacy from gawking visitors while at the same instant enthusiastically promoted itself. Casting from locals meant that roles are played by amateurs— with day jobs as nurses, pharmacists, municipal administrators, and business owners. Actors who played roles of young characters over time aged into the roles of older characters.

Thousands have flocked to see the Mockingbird play. For an otherwise depressed town, it has provided an economic uptick during its annual month-long run. Over the years, the company gained international attention, leading to performances in such places as Israel, Hong Kong, England and The Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. But those places cannot capture the production’s authenticity precisely because they are not Monroeville. There is a pang and a poignancy to TKAM when told by its own people, in a genuine Alabamian drawl, in a simple brown and white painted courtroom with its famous segregated balcony gallery and its wooden floorboard creaks that echo from 1934 injustices. The evening time play carries an intense authenticity; it opens in the “amphitheater” behind the courthouse, in 90 degree heat with the Southern scent from a nearby magnolia tree and the faint salt-smell in the air from an occasional gulf water breeze. Atticus is all the more believable walking on the adjacent public sidewalk from his law office onto the “set.” The terrorism is palpable as a lynching mob drives an unrestored 1934 Ford pickup immediately in front of the audience—its vigilante-passengers shouting and threatening a watchful Atticus, the only watchman protection for a jailed Tom Robinson – so that he lives until his trial the next day.

The mob scene occurs just as the actual sun is setting- portending Tom’s ultimate fate. The audience moves into the courthouse for Act Two’s trial. Like any trial, the gallery is open for public seating; like any 1934 trial, the jury is composed of twelve white males—pre-selected from the audience at will-call. Atticus, played by a local insurance broker, saunters between the witness stand and defense table. He grabs the lapels of the sweat-stained seersucker costume he has worn for twenty-seven years; his questions expose inconvenient truths, and provide for Tom the due process promised. Atticus, Judge Taylor, the tourist-jury and the audience know that Tom will be convicted based on the racial codes of conduct rather than the facts; that Tom’s ultimate fate of 17 bullets to the back will be met before any appeal is heard; that “Atticus had used every tool available to free men to save Tom Robinson, but in the secret courts of men’s hearts Atticus had no case.”

“THERE ARE SOME MEN IN THIS WORLD WHO ARE BORN TO DO OUR UNPLEASANT JOBS FOR US…”

To this line, as Miss Maudie Atkinson explains to Scout Atticus’ important, but futile, representation of Tom, she adds “Your father’s one of them.” Just as in Macomb, a prominent white professional in antebellum Milwaukee undertook trials to do “our unpleasant jobs for us” in the advancement of civil rights.

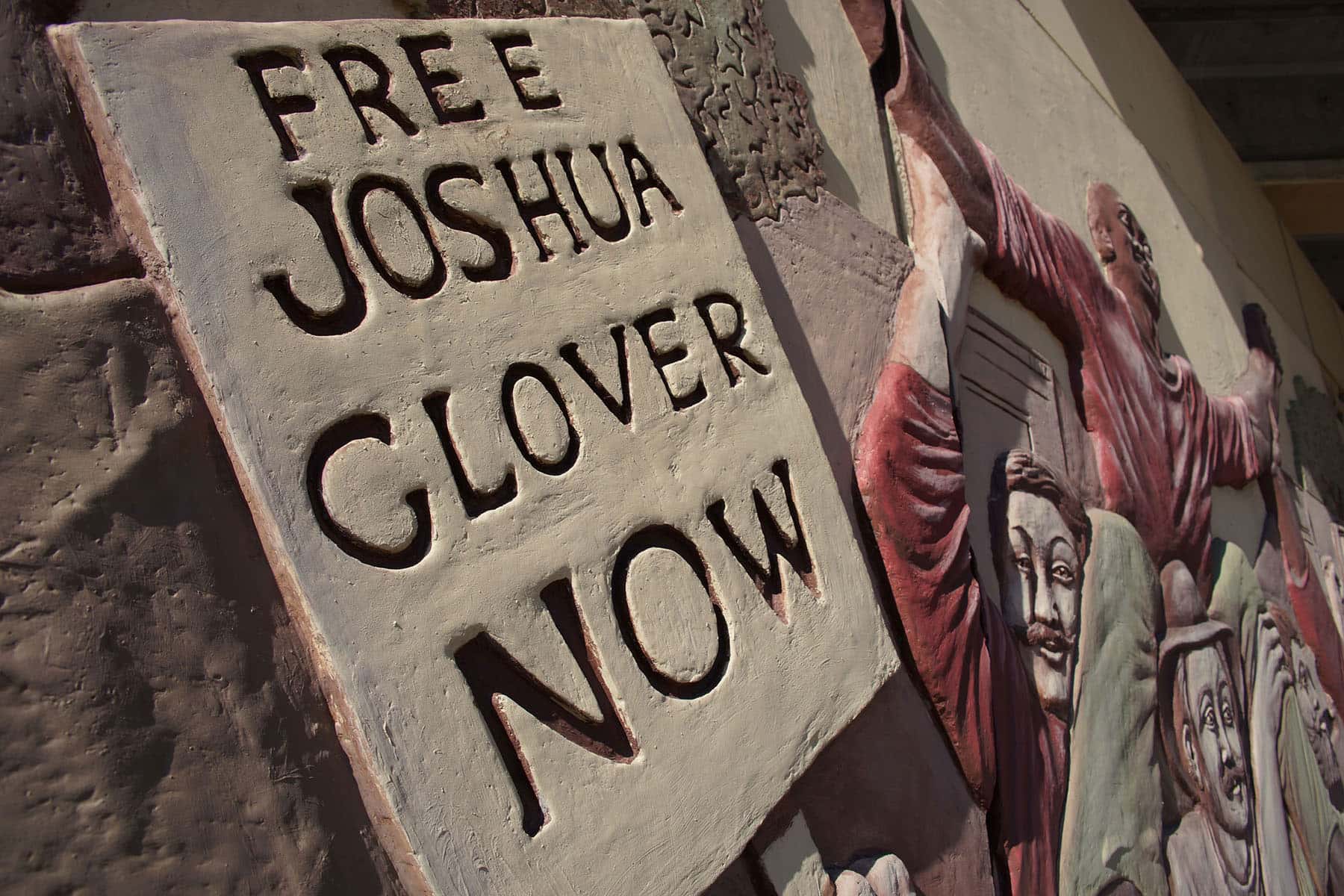

In March 1854 Sherman Booth, a newspaper owner and abolitionist, learned that Joshua Glover, a runaway slave from Missouri, was captured in Racine and being held in a Milwaukee jail for return to slavery under the United States Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Outraged, he rallied thousands in then-Courthouse Square (now known as Cathedral Square) to protest the incarceration of Glover. The citizenry responded as a mob and, unlike the mob facing Atticus at the Macomb jail, were successful in battering down the jailhouse door. Glover escaped to freedom, eventually settling in Canada.

Booth, however, was arrested two days later for “aiding and abetting an escaped slave in violation of the Fugitive Slave Act.” And then began his long six years of litigation in state and federal courts; his periods of incarceration and freedom (via habeas corpus petitions or mob breakouts); and his publications of inflammatory editorials and delivery of fiery speeches. All of this strife enthusiastically undertaken and endured– largely to his own detriment.

He won, but eventually lost on appeal, several jury trials. The Wisconsin Supreme Court famously declared the federal statute unconstitutional several times. The Wisconsin justices also defied the United States Supreme Court for four years, refusing to send its files to Washington D.C. Ultimately the Wisconsin Court relented, and no one less than the notorious Justice Taney (of Dred Scott fame) wrote the decision which overturned Wisconsin’s decision; the U.S. justices established the important legal doctrine and precedence that states could not eclipse federal judgments or overturn federal law in cases arising under the U.S. Constitution and federal statutes. The Fugitive Slave Act would stand; shortly thereafter the Civil War’s end would nullify its potency.

After Booth’s legal proceedings left him in economic ruin, separated from family and plagued by other indictments, he sold his printing press, divorced his wife and refused to honor other court convictions. However, he continued to fight for abolition; he continued attempted jail break outs until he was successful; he continued to do “our unpleasant job” of anti-slavery advocacy. When his antics proved costly for the local federal marshals, President Buchannan freed Booth from federal incarceration by remitting his fines—not by granting a pardon.

Like Monroeville’s courthouse square memorial to the fictional Atticus, Milwaukee’s old courthouse square bears an historical marker recounting the “Rescue of Joshua Glover.” This marker on the corner of Jackson Street and Kilbourn Avenue is complimented by a similar marker at the corner of E. Glover Avenue and N. Booth Street.

Both markers quietly honor the Milwaukee newspaper editor who told the truth; who was one of “them” who was born to do our unpleasant jobs for us.

PROLOGUE: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE DRAMA

Like the fictional story of Atticus and Tom Robinson, the historical story of Booth and Glover was captured in two 1998 plays, commissioned by the Milwaukee Bar Association and the Wisconsin Supreme Court, respectively. The dramas, written as the judicial branch’s commemoration of the state’s sesquicentennial, captured the most significant Wisconsin court case in the state’s history– civil rights or otherwise. Experiencing the dramas keeps Wisconsin not only educated about its history of abolitionism, but also reminded about its present of yet-to-be-realized civil rights.

Recently, the administration of a school district in Milwaukee County decided to cancel its high school production of TKAM, merely hours before its opening night performance. The decision was prompted, in part, by alleged threats of proposed protests about the use of racially-charged words included in the play, and by alleged insensitivity about the slurs affecting the cast and student body, and by a host of other topics conjured about the play’s unrealized and/or lost educational merits. The administrative decision led to remonstrations from a coalition of groups concerned about artistic censorship, protest suppression, and lost opportunities for discussions about race within the notably segregated Milwaukee city and county.

The superintendent’s decision was reversed. The district rescheduled the play’s run, and then…. reversed itself again and reinstituted the cancellation on the second “opening night.” The ultimate outcomes and learned lessons from the abrupt cancellations are yet to be determined.

However, upon hearing about the local Milwaukee County incident, I recalled thoughts expressed by Macomb’s “Judge Taylor” in Monroeville. The actor, a local insurance agent who has played Judge Taylor for seventeen years, included in his biographical liner notes the following:

“With ironic relevance today, TKAM shines light on society’s resurging intolerance and bigotry. Although revisiting evil, Judge Taylor winds up being a cog in the machine as Pontius Pilot was.”

During a short chat after the Monroeville TKAM, “Judge Taylor” commented to me about Alabama’s substantial efforts to publicly document its past civil rights attitudes and abuses; he wanted to be sure that before I left the state that I plan to see Montgomery’s newly opened National Memorial for Peace and Justice. His final remarks to me resonate: while he appreciates the hundreds of persons who visit Monroeville to experience the drama he regrets that the Mockingbird Foundation can’t seem to get the locals to attend the play. The Civil Rights Trail, essentially, serves visitors’ curiosity, not natives’ reconciliation with the past or conflict resolution in the present.

His comments were insightful and heartbreaking and, on reflection, true. Weren’t the BP gas station attendant, the Walgreens’ cashier, and the Mockingbird Suites desk clerk each friendly to me and were curious about the origins of my Midwest “accent?” But weren’t also each of them unable to answer any questions about the play’s Old Courthouse location or any performance details?

They are left as unaware of the injustices against Tom Robinson and of the courage of Atticus Finch played out in the racial attitudes and culture of their hometown as are the would-be attendees of the recently cancelled TKAM performance in Milwaukee County.