This February the Wisconsin GOP marked Black History Month by removing the name of Milwaukee native, civil rights activist, and Super Bowl quarterback Colin Kaepernick from a resolution honoring his efforts and those of other African-Americans.

As if inspired by the NFL, earlier this month an 11-year-old African-American child in Florida was arrested for refusing to stand for the national anthem. And in Virginia, the Governor and Attorney General marked the occasion by acknowledging they wore blackface during the 1980s. An act channeling the minstrel shows of old that sought to emasculate Black men and fueled the ignorance, disdain, and hatred that cost thousands their lives, but not their dignity.

The actions of a professional athlete, a child, and two older White men during their 20s seem disconnected, but in their own way, each has become a part of Black history. How it is recorded, however, is not up to them. The history that is read about in books, online, or viewed on TV is not determined by those who live it, but by those who write about it. The end result is that the heroism and sacrifices of millions are systematically whittled down to a handful of names hidden in a chapter, cut and pasted into a resolution, or dropped into a sentence.

Conversely, countless acts of inhumanity and discrimination, and the names of those associated with it are often strategically kept from those same history books in an attempt to distance the majority in America from that part of our nation’s past.

The accomplishments of Dr. King, Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, and Shirley Chisholm, and others so often mentioned during Black History Month are to be honored and forever serve as inspiration. But a deeper review could introduce the public to the likes of Fred Hampton, Fannie Lou Hamer, Rev. George Lee, and more recently Tarana Burke.

We are far greater than what we have been taught to realize. Looking beyond what is in our history books, or what occupies space on Wikipedia, we come to understand that within our own families and community there are also individuals worthy of acclaim and recognition.

They are Black history and remind us that inspiration is always within reach.

The history of African-Americans in this country is a perpetual creation spanning hundreds of years, formed over generations, across villages, within homes and inherited in our hearts at birth. It compels us to recognize that one does not have to march on Washington, cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge or be able to float like a butterfly, sting like a bee to register as historic.

To that end, I have come to realize and humbly accept that I too am a part of Black history. Such a claim does not need approval by a statewide legislative body, nor checked for spelling errors by editors of an academic textbook. It is one that I was born with.

I am Black history because I come from a line of historical figures who gave me their experiences as a person of color in America. And if I, a Black man from Ohio, am Black history, then what does that say about the tens of millions of others who overcame equal, if not far more challenging trials.

I reflect upon those in my life and how magnificent their accomplishments are. Their resilience and courage are a part of my inheritance, and their experiences serve as a guide I follow throughout my life. Their stories do not grace a single page of a textbook, but their lessons are part of my education.

I think of my uncle, a veteran of the Armed Forces who in the 1960s woke up to a cross burning on his lawn in Ohio. The next day going to his commander and expressing outrage, stating that this would not stand and demanding resolution. And on the day that followed being told that he and his family would be promptly stationed off the continental United States. A relocation forced by an act of hate from misguided men, with the resolution my uncle sought never being given.

My uncle is Black history.

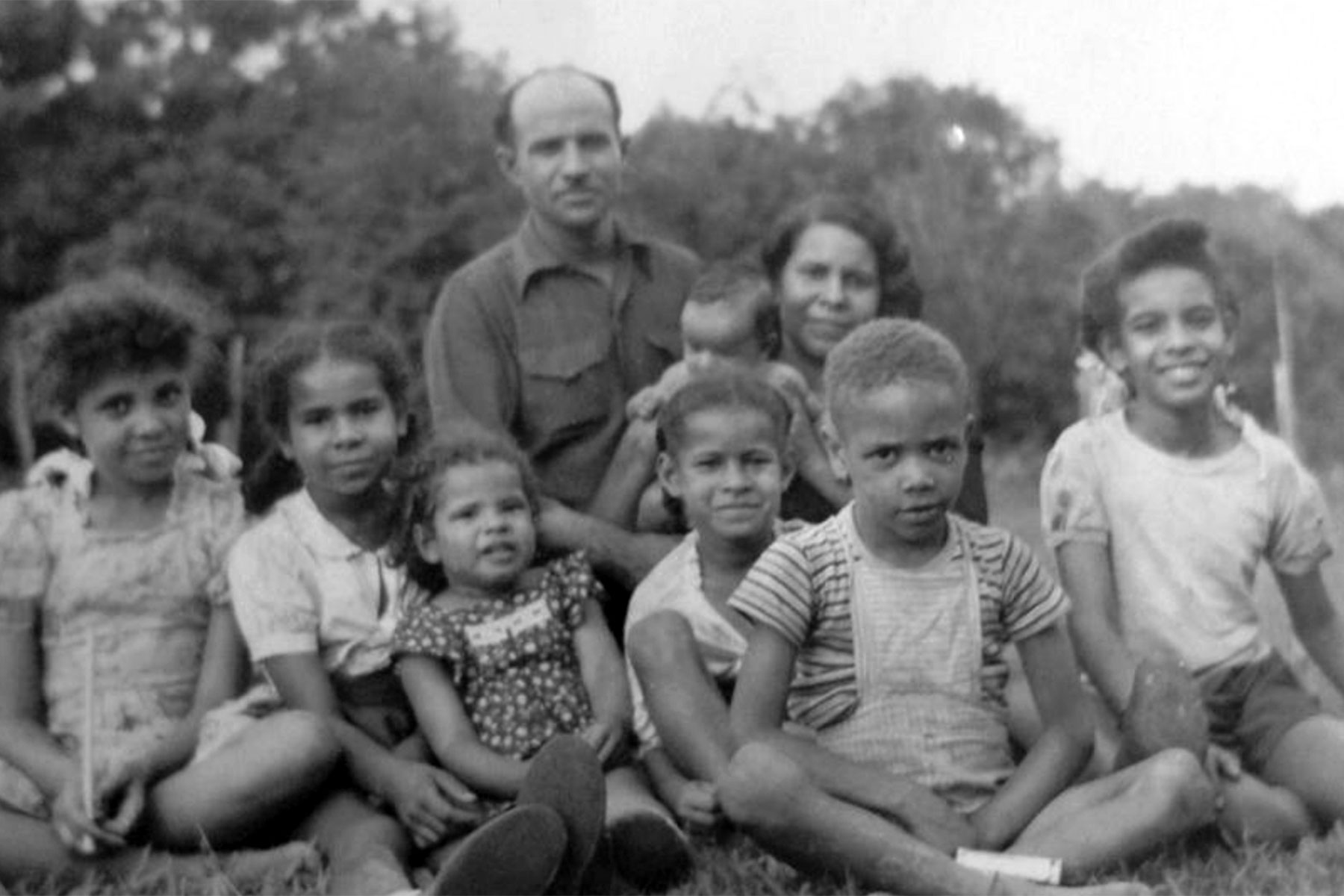

I look at what it took for my parents to buy the land my childhood home would be built upon. Money in tow, they went to purchase a two-acre plot in Delaware, Ohio, only to have the owner refuse to sell it to a Black family. Undeterred they created a workaround and gave their life savings to Tony Haberman, a Jewish man they barely knew who would buy it for them in his name. The next day the deed was signed back over to my dad in exchange for nothing more than a handshake and a promise kept. An act of trust that leads to four children being raised in the home my dad built with his hands, brothers, cousins, uncles, and friends.

My mom and dad are Black history.

I shake my head recalling how the school my siblings and I attended put on minstrel shows up until the late 1960s. The shows discontinued only after my parents protested and demanded an end. Soon thereafter accusations flew that the Black Panther Party “put them up to it.” An inaccurate claim that revealed how some people were unable to see the dignity of a Black family in rural Ohio. A family that was not “put up to it,” but simply was not going to put up with it any longer.

My siblings are Black history.

Even in the seeming mundanity of my own life, I reflect upon the experiences of my youth. And while the majority was marked with memories of little league, popping wheelies, and friendships with White kids in rural Ohio, it also had a fair share of the unwanted rites of passage many experience in America. Those ranged from being told to clean toilets at six years of age by my first-grade teacher, to being called the “n-word,” or listening to a handful of “no offense” jokes. With the insight, wisdom, and support of those around me, I came to realize that such actions did not reflect who I was. To the contrary, my family and our history conveyed that those actions were merely futile attempts to indoctrinate a child into who they thought I was. Attempts meant to mask the reality that such acts are instead an illustration of how insecurity, entitlement, and racism can animate the misguided actions of many across our nation.

I am Black history.

Such a claim is made with deference, humility, and full recognition of those whose names are not well known, but whose accomplishments far exceed those memorialized in statues or who occupy the highest office. Their lives matter and to honor them we must see Black history in ourselves, our home, families, and community. We must know that their legacy of courage, greatness, and resilience serves as a template and a guide for who we must become.

You are Black history.

Understand it, embrace it and ensure that your children learn that they are more than what is taught in school. Teach them in the classroom of your home, with you as instructor and your child as the student. Help them recognize how their aunts, uncles, and elders are a part of what makes our history so great. Viewed through this lens it allows us each to claim our inheritance with a sense of pride and a responsibility to ensure that our children recognize what is known from the moment they enter this world.

They are beautiful, gifted and yes, historic.

© Photo

Kenneth Cole