The classrooms may be secure units with half-circles of cells, but a team of teachers and I have recently launched a student research project called “The Examined Life” that will reconnect a group of incarcerated youth at the Vel R. Phillips Juvenile Justice Center to themselves, to the outside community and to pathways around the obstacles in their lives. Influenced by Socrates, Paulo Freire and newly acclaimed author Shaka Senghor, we will encircle the students with a pedagogy (or theory and practice) of self-empowerment and critical consciousness as we take on the role of the students’ research assistants, giving them space to read themselves and their world more closely and guiding them to eventually create a presentation of their needs to a community that desperately needs to hear their voices. This is the first in a series of stories about the evolution of a new pedagogical approach for Milwaukee juvenile justice system.

“The unexamined life is not worth living.”

According to Plato, Socrates declared this maxim at his trial for corrupting the youth of Athens with his particular brand of critical thinking. It has inspired the name of a new research project that nearly two dozen teenage boys in the Milwaukee County Accountability Program (MCAP) at Vel R. Phillips Juvenile Justice Center began last month.

The general population of youth at the Juvenile Justice Center is between 11-17 years old, mostly African American and mostly there temporarily while they wait for court orders, group home or residential treatment center placements, monitored probation. Of the up to 120 youth (there are currently about 70), all served by the Vel R. Phillips School, up to 24 of them are placed in the MCAP program. These youth are often on court-ordered supervision, have committed a new crime or are considered at high risk for recidivism for crimes such as robbery, carjacking, weapons possession or armed robbery. The program is part of a one-year supervision order, which includes up to 180 days at the Juvenile Justice Center, then monitored and mentored supervision after release.

This year, while the young men in MCAP continue their education at Vel R. Phillips, they are engaging in a unique research opportunity dubbed “The Examined Life,” or the Individualized, Interdisciplinary Investigation Portfolio. The IIIP will connect the work students have been doing in English, Civics, Map Your World and Math classes, allowing students to integrate skills like reading and writing, exercising one’s rights, neighborhood asset mapping, and data analysis. It will be supplemented by multi-genre creative writing and the reading of an inspirational autobiography. And perhaps most importantly, as their research begins, students will write to community leaders who can help them answer their research questions and bridge the gap between the inside of Vel R. Phillips and the communities they’ve left behind temporarily.

With the assistance of myself and all their teachers, each student will select the three biggest problems that hinder his ability to feel and live as a valued and valuable member of society. Then, all students will answer two essential questions: How can these problems be solved and what can I do to address these problems? Because they are kids – and incarcerated kids on top of that – the project will give them a unique opportunity to let the adults in their world know what they need from them.

OUR OWN PROJECT OF DISCOVERY

The process of creating the framework for the “The Examined Life” portfolio has been – for me and Vel R. Phillips School – a struggle of discovery in itself.

The discovery process began many months ago. Bill Anderson, one of the schools two principals, informed me that “in the past, the school worked on separate and traditional subject matter like reading, writing and math. When I came to the school two-and-a-half years ago, everyone was working in isolation and doing things on their own.” When last year, the and his co-principal Dean Heus, began seeing signs of collaboration happening organically among the teachers, they were energized by what they were seeing and encouraged more from their staff.

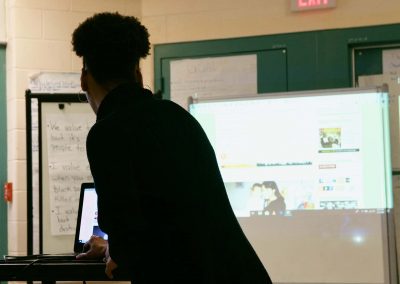

Special education teacher Rebecca Kirchman created a process by which all her peers could see what everyone else was teaching each week, discouraging overlaps and encouraging collaboration, support, and building upon each others’ lessons. Civics teacher Rob Kalpinski and Map Your World’s Doug Baisley worked together to have students research influential Black historical figures during Black History Month and present their findings on posters to members of the school district.

Since then, more and more 21st century learning skills have emerged: math teachers Hannah Erl and David Mahdasian teach visual literacy with data analysis of graphs and charts and English teacher Krishana Robinson has introduced listening circles and is investigating ways to have some of the boys enter a podcast to an NPR contest. However, according to Robinson, she and her peers still “struggled to wrap our heads around a framework to pull it all together, especially in our particular setting with its particular restrictions and culture. How can our teaching be more project-based, cross-curricular, and be authentic and real-world? And can we do this together?” They were looking for the language and vision to put the pieces of their high-level expectations and high-level projects together.

Principal Anderson says, “I know it’s hard for teachers, for sure, to just be told, ‘Go collaborate,’ when they haven’t done it very often.” He sees potential, however, in “having students connect with something that resonates with them, allowing them to take a journey inward, to ask questions about their situations and their world” and hopes that “this will inspire and engage them. Just having this III Portfolio will be healthy for everyone, including the teachers.”

When I came on board as an independent consultant, I learned that the teachers were in the midst of pulling together an individualized research project that would have students define and prove a problem in their world then propose solutions. Baisley and the Civics team had created resource folders for individual students and begun filling them with articles; they had also recently had them finish mapping community assets in their home ZIP Codes; and since then students have written, revised, and sent letters to many of those community assets, inviting them to visit Vel R. Phillips and share their wisdom. When I first met the MCAP teachers as a group, they were trying to determine how the project would connect across all content areas.

I remember being excited by all they had been doing already and hearing a desire to do something as cool as or even cooler – even more authentic and real-world – than last year’s Black History Month poster presentations. I also heard a need for a framework, a synthesis and a purpose for doing cross-curricular, project-based work.

In addition, the teachers spoke of the students’ effort and hard work, their successes and resiliency. I saw pride in their eyes. MCAP students seemed to have a lot of additional advantages that could help them, too. Their extended stay at Vel R. Phillips was contained to a secure unit (or pod) where they lived, went to classes, at their meals, received programming. Each of two pods has a dozen cells. There, a sense of community could be fostered. The MCAP program also sustains connections to the boys’ families, access to community resources, weekly counseling, and mentoring and motivation by Running Rebels. In addition, they receive substance abuse education, utilize restorative justice and begin to change their mindset with Juvenile Cognitive Intervention Programming.

I learned that the outcomes of the MCAP program are many. Dean Heus, the other principal of Vel R. Phillips School, witnesses how students grow in maturity: “This is due to the efforts of the students themselves, families, Running Rebels, county supports and other helpful people like our educators. And that goes beyond credits earned or if the students re-offended or other metrics. When students ‘complete’ their MCAP programming (both the detention portion as well as their post-release ‘community phase’) there is an MCAP Graduation event that Running Rebels hosts. You hear students say incredibly heartfelt, empathetic things about the adults who support them. You hear students talking about their jobs and/or the schools they are attending.” And Robinson notes that the MCAP students grow socially and emotionally: “Students are more trusting, more willing to engage with new faces, less aggressive with peers and staff and more playful and feel safe trying new things.”

Feeling playful and safe myself, then, what I proposed was a revised version of what the Civics team had already begun and ways the other teachers could connect in meaningful ways. The IIIP, or individualized, interdisciplinary research project, would have students identify a single social problem and seek solutions by using Aristotle’s stasis theory, which uses key questions to discover one’s stand on an issue. They would ask questions of fact, cause and effect, definition, value and finally policy (What to do?) to get to the heart of their issue. Then, we would guide them through the writing of an essay using Ken Macrorie’s “I-Search” process, a metacognitive approach in which one actually narrates one’s research journey. They would collect discipline-specific artifacts that demonstrated their learning (such as a graph they created in Math class to understand food deserts or an annotated article from Civics), and the teachers would continue to teach their regularly planned curriculum but also guide the students through the research process, differentiating their approach for each student.

I had used the I-Search method many times, at Marquette University, Pius XI High School and The Prairie School, most recently as an integral part of seniors’ year-long capstone projects. Stasis theory was one of the first things I learned and taught as a graduate student at Marquette. And portfolio was my middle name. There was no reason, I believed, that students at Vel R. Phillips could not tackle a project like this. It would offer choice; it would connect their classes and reveal relevance; it would teach them problem-solving skills; it would connect them with the outside community. All good things, right? It didn’t matter who the students were, what they had done, where they were now. They could get it done. High expectations. Rise to the occasion. Show the community what they could do.

I got some skin in the game when I met with the two groups of students during Robinson’s English classes and brought with me what I hoped would be a simple and meaningful way to prepare them for their research. At 8:30 am, with my materials spread out at the tables in the pod, I heard a toilet flush, caught a glimpse through one cell door window of one boy brushing his teeth, another running his hands through his hair. The officer clicked the button to unbolt their doors, and the boys shuffled out like most of the teenage boys I had ever seen at 8:30 in the morning. I had been in Robinson’s classes before, sharing my work with ZIP MKE and leading them in some visual literacy exercises, so at least there were some familiar and friendly faces, too. So far, so good.

I gently rang my Tibetan singing bowl, informing them that it would signal either that I desired their attention or that we would be transitioning to a next step. I encouraged them to talk among themselves, then, after twenty seconds, rang the bell. The first class needed five deep, slow gongs, the second class only two.

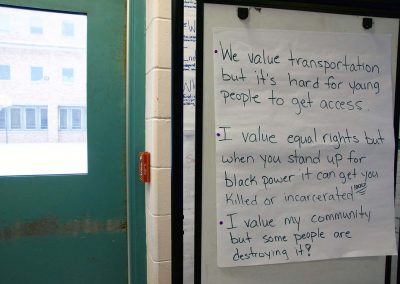

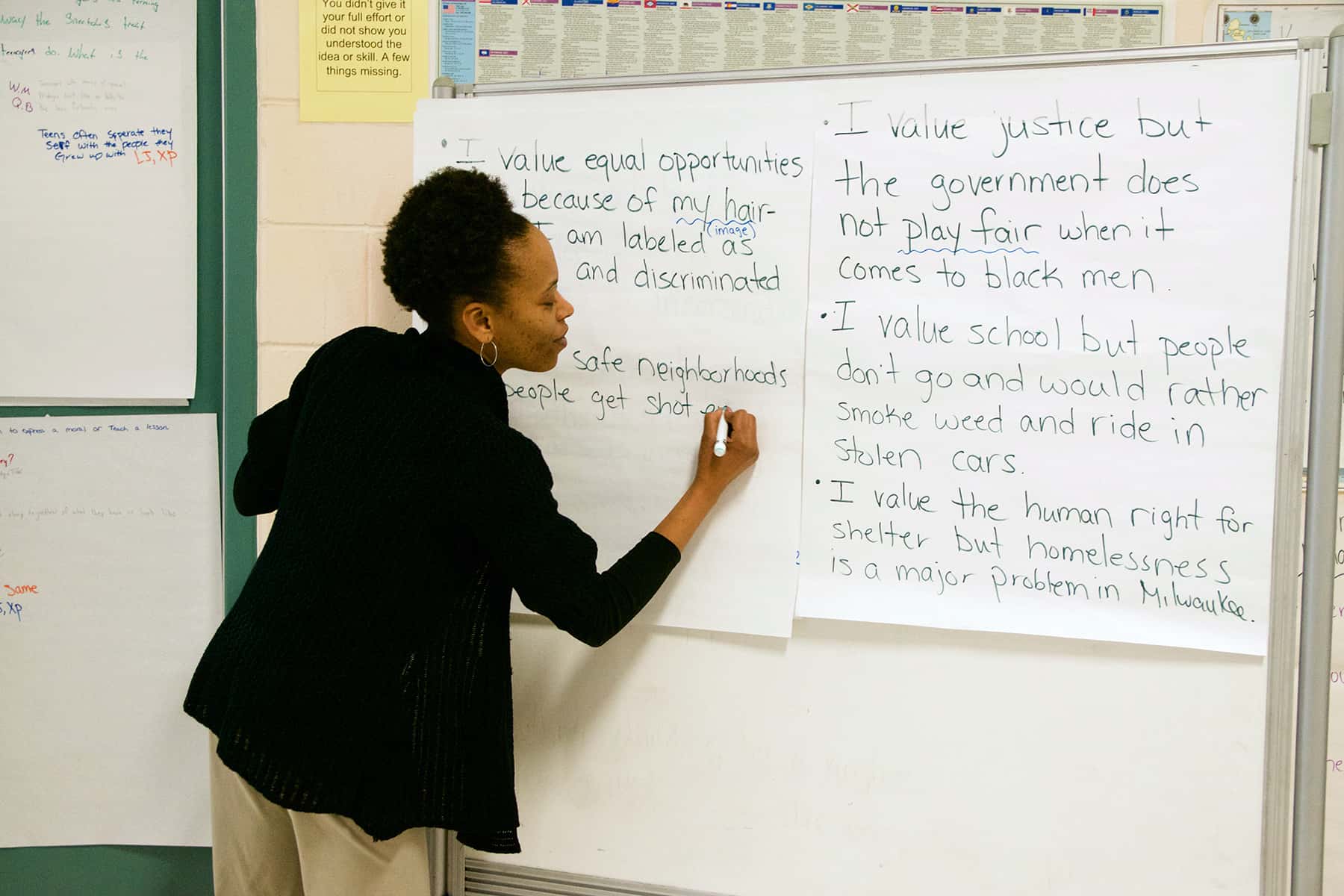

They would need a problem first, so I wanted to help them uncover problems in their personal lives, then in society. I gave them a list of 200 values (like love, honesty, and trust), asked them to circle the most important values to them, and rank them. To my surprise, they all sat, in relative silence, studying the five columns of words, circling value after value after value with their sharpened pencils with eraser caps: love, honesty, trust, integrity, hard work, family, toughness, care. It felt good to be leaning over their shoulders, praising their choices. I got a few fist bumps. Boys would call me over to show me their lists. Just like old times. And in the second class, when one at a time they announced their top three values, I urged their peers to repeat them out loud and clap. “Family. Athleticism. Love.” “Family! Athleticism! Love!”

While some of them kept circling values as if they needed reminding that those things still exist in the world, I rang the bell and asked the classes to now add “Big Buts” to their top values (this garnered some giggles, thankfully), as in “I value love, but too often I see people mistaking love with control” or “I value integrity, but I’m not always honest with myself or others.” I rang the bell and they graduated to an even more difficult task: adding “Big Buts” to things that society values, like a good education: “I value a good education, but the achievement gap between black and white students is so high” or “I value healthy eating, but eating healthy can be expensive.” These “but” statements were problems, I explained. They struggled, as they should have, with this step – and we ran out of time – so they only made a little progress on this step, but Robinson and I agreed they would need more time to identify bigger problems beyond themselves.

The boys said goodbye. A few tried hanging back so they could ring the bell themselves. I showed them how to swirl the edge to create a rich, meditative note. The officer urged them to return to their cells, so they shuffled back with the others. Each green door clicked shut.

Wanting to maintain their initial enthusiasm, I wrote a follow-up letter to them (an empathic practice I had maintained for many years when in the classroom) that reading specialist Heather Peters copied and placed in their ELA folders for me. I thanked them for sharing their values with each other: “My guess is that you don’t do that enough, not because you are young men but because people in general don’t share their values with each other enough. It’s so easy for us to rattle off our problems, what we see wrong with the world, without first naming the good things about it.” And I praised them for discovering problems: ”You created your ‘Big But’ statements nicely, too, seeing how the world doesn’t always value (or how it devalues) what’s important to you. This was good to see. This was sad, because all of you have important values, all of you are of value and should be valued. But it was also good, because once you name a problem, you can begin to solve it.”

I was optimistic: the students had responded with attention and enthusiasm, and they would hear and read my praise and care. I was doing things right.

The first day.

THE EXAMINED LIFE

After the problem-creation sessions I led, I met with Robinson to discuss our next steps. Something that day seemed off – perhaps it was a particularly tiring day for her – and we seemed to be tiptoeing around the next steps. That’s when she gently slapped me with some reality. She noted the students’ general lack of intrinsic motivation. While they had enthusiastically devoured the values and “Big Buts” exercise the first day, she told me that her next class meeting with them, when they were to narrow their choices to researchable problems, seemed to many of them like déjà vu. Nothing new. They were resistant: “We did this already. I filled in my blanks, Ms. Robinson. Can we read instead? I just want to go back to bed.” How, Robinson asked, would they be able to sustain interest, motivation and effort over an extended period of time, especially on one problem? Each new round of stasis questions would seem like déjà vu and students would likely rush and give up with “I’ve already solved the problem!”

I knew the difficulty in sustaining any students’ attention on long-term projects, but Robinson reminded me that the brains of the students at Vel R. Phillips had learned to prioritize basic survival needs over temporary pleasures (like naming personal values): Outside the facility, it might have been the need for food, shelter or safety, the need for money to pay the bills that their parents weren’t able to pay because of a drug addiction, the need for a joyride to give them a temporary feeling of power. Inside the facility, their brains might be prioritizing all that plus the constant reminder that they had been separated from the rest of society for the past few months. Anger, resentment, loneliness, isolation. Our approach to this project would have to be trauma-informed.

I sensed that Robinson, while still hopeful, was doubting the efficacy of the IIIP process. I admired her honesty, even as it felt like a wrench in all that we had designed. She paused, though, to pull a book from her desk drawer, as if she had discovered the key to our intrinsic motivation dilemma and had been waiting for the big reveal. The cover featured a Black man walking hand-in-hand with a young child. “The students,” she announced, “are actually fighting over this. They want more copies so more of them can read it. They want to bring it back to their cells. They want to talk about it.”

Shaka Senghor’s Writing My Wrongs: Life, Death, and Redemption in an American Prison had, I learned, tapped into their intrinsic motivation. They didn’t have to read it, but they wanted to. Senghor went to prison for murder when he was nineteen and served a nineteen-year sentence, during which time he discovered the redemptive power of writing. When he was released, he became an activist and mentor who has served young people all over country. According to Robinson, Senghor’s story reminds them of their own stories, their own backgrounds, their own need for redemption. She says that “students have expressed a desire to learn more about how Shaka Senghor overcame the obstacles many of them are facing.” This is what the young men needed and wanted: models of redemption, solutions to their problems, agency and freedom and care.

We both sighed. We knew our plan would have to reexamined. But how?

The temptation would be to move ahead without revision – that would have been the easy road – and hope that somehow the MCAP team – who was just getting up to speed on the original version – could motivate the students enough to redeem the time. But when I opened Senghor’s book and discovered that he had chosen Plato’s quote as the epigraph, I saw it as a definitive sign to reexamine our original plan.

We agreed that the IIIP project needed Senghor’s book to anchor it. We also agreed that the research process needed simplifying, focus, and an essential question – and purpose. The new version should remain an individualized, interdisciplinary investigation portfolio – that was a good risk we were willing to take – but we wanted it to emerge from a greater purpose: to communicate students’ needs and ideas to a community that has, in many senses, failed them. To give them greater knowledge about the problems they see in their world, to allow their voices to be heard, to offer them the possibility of redemption and positive agency.

I went home that night and penned another letter to the students which introduced a new process and a new purpose. I gave it a less jargony name: “The Examined Life.” I created the new essential questions. I simplified the research they would do and the reflections they would write; I explained the portfolio more clearly. Most importantly, I wrote to them, not at them like a traditional assignment description. (Thankfully, we hadn’t gotten to the point of introducing all this to them, so it would sound like we had it planned this way all along.) Senghor was my hook:

“Senghor writes, “What I now know is that my life could have had many outcomes; that it didn’t need to happen the way it did.” The thing is, it did happen the way it did for Senghor. And that’s a problem. And it did happen the way it did for you, too. That’s a problem, too. So things need to change. You need to change. This is why Senghor wrote his book about finding redemption for what he had done and why he does so much work now helping individuals and communities throughout the country solve their problems. When you return to the larger community, it will likely be the same as when you left it temporarily – even as countless organizations and movements are constantly working to fix our problems. But the work needs to be done, and the workers need to hear your voices. You can be just as much of a voice and just as much of a change-maker as Senghor – if you choose to be.”

I end the letter: “To borrow Senghor’s phrase, your research is all about “righting/writing society’s wrongs.”

It’s about letting the community know – in writing and in person – what you need to happen. The community has not heard from the mouths of students at Vel R. Phillips Juvenile Justice Center School. But (here’s the Big But!), now they will.” The letter’s signatures include my own, the entire MCAP teaching team and the school’s administrators. It is like a contract stating that we were all willing to take this risk and go on this journey of self-examination and social critique together.

I was getting better. We were getting better. We were doing things right.

A PEDAGOGY OF SELF-EMPOWERMENT

Without knowing it at the time, my rethinking of the IIIP, my looking for a “different hook” and even my renaming it “The Examined Life” was influenced subconsciously by Brazilian educational philosopher and activist Paulo Freire. I realized this when I Googling something like “How to make a research project for incarcerated youth more relevant and transformative” and Freire’s name appeared in a link. Bingo. Why hadn’t I thought about him before?

I hadn’t thought about Freire for awhile, since I haven’t been in a classroom for almost three years now. But it all came back quickly. Freire’s pedagogy rejects the dominant “banking” model of education in which teachers deposit information into students, who file it away and withdraw it when required (especially for tests). He insisted that teachers “must abandon the educational goal of deposit-making and replace it with the posing of the problems of people in their relations with the world.” For him, acknowledging students’ lives and giving them the tools to recognize and solve problems, to imagine and act on a better world, “affirms men as beings in the process of becoming – as unfinished, uncompleted beings in and with a likewise unfinished reality.” Why else learn math or civics or reading or writing but as a way to become?

In 1962, then, he created Culture Circles in Brazil that allowed 300 sugarcane workers to teach each other two forms of literacy: how to “read the word” and how to “read the world.” The dialogic circles allowed the workers to collaborate with each other to say “This is our world, here’s what we think about it, here’s what we imagine it could be, here’s how we’re going to say it and here’s what we’re going to do about it.” Within 45 days, the workers had taught each other how to read. The workers learned how to read in the context of their own world, through dialogue and reflection, and with purpose and power: being literate meant they could register to vote. The Brazilian government at the time embraced this groundbreaking methodology and approved thousands more around the country.

The student workers had reached conscientization, or critical consciousness, by breaking what Freire called the “culture of silence” that forced them to speak with a voice that was not their own, to accept their oppression, to internalize a negative image of themselves. Freire explains, “The oppressed are not only powerless, but reconciled to their powerlessness, perceiving it fatalistically, as a consequence of personal inadequacy or failure. The ultimate product of highly unequal power relationships is a class unable to articulate its own interests.” His seminal text, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, appeared in 1962.

A 1964 coup d’état, however, threatened by so many self-empowered citizens, imprisoned Freire for 70 days then exiled him from Brazil. In order to stay in power, they couldn’t have people believing that “they can make and remake themselves.” Like Socrates, Freire had been imprisoned for teaching people how to think for themselves.

I am fascinated by the dynamic that is emerging. Incarcerated boys in Milwaukee embarking on a new project with the powerful words and ideas of three formerly incarcerated men from ancient Greece, northeastern Brazil, and Detroit, Michigan. Three men who changed or are changing how we read ourselves and the world. I’m not expecting these teenage boys to all of a sudden become powerful, influential gods of writing and revolution. But I feel a new level of urgency. I see each MCAP student as a potential Shaka Senghor, an emerging Socrates, and now a loud-and-proud Freire. Redeemed, rebellious, ripe for conscientization.

BUT WHAT IF IT “FAILS?”

In the backs of some our minds, however, are the inevitable questions: What if the III Portfolio doesn’t succeed? How will I and the MCAP teachers and Vel R. Phillips’ administrators measure its success? And now, especially for me, what if the project’s implementation doesn’t live up to the triad of powerful philosophies?

There are reasons it could fail, for sure. English teacher Robinson, perhaps the IIIP’s most vocal champion, notes that the biggest obstacles to student growth in MCAP are transferability and the itinerant population.

“Students,” she worries, “can show willingness to change and a growth mindset with the expectations, support and encouragement, but what happens when they return to the community? How much of this support follows them to help prevent recidivism?” She also notes that “when new students arrive, they have to adjust to the culture and climate we are trying to create and sometimes they can rock the boat.” Then there’s that intrinsic motivation that we may or may not be able to activate (or keep activated) along the way. From a student perspective, what if they just don’t buy in, despite Socrates, Freire and Senghor – and our best intentions and practices? And from a teacher perspective, what if the team can’t make it work?

Principal Heus believes he has opened the door to something new but, to him, thrilling. He reminds us of something that is often lost in the standardized, bureaucratic shuffle: that “schools are learning organizations, so everyone learns. So while a portfolio-based project across content areas is a new thing for us, the structure of MCAP and the length of stay of MCAP students lends itself to this sort of project.” Heus has faith in his teaching staff and their ability to fail forward for the sake of the students: “If we have the mindset as adults that we are nimble enough to pivot and adjust throughout the project as needed, then that in itself will be a success.

Thankfully, Principal Anderson embraces the risk wholeheartedly as well: “From a holistic point, it can’t hurt. I truly believe our kids will be more highly engaged. I mean, being locked up in a facility for 120 days or more, you get into a routine. It’s not healthy for the brain. So anything that can engage them and help rewire their neural pathways in healthy ways will be beneficial. Why not try something new to help them ‘re-set’ in a positive and supportive environment?” For Anderson, the project’s success will mean “the young men being proud of what they created, knowing that they took a challenge and learned about themselves, and feel the success of sharing their work with the community.” He adds, “I want it to be a positive experience of learning for them. I want them to feel those endorphins that get activated when they’re successful versus feeling the adrenaline rush of, say, stealing a car. With this common project for all the teachers and students, we’ll let it go and then come back and reflect on it so we can improve. We need the students to see us collaborating and working to care for them.”

In the end, Robinson is choosing to err on the side of Socrates, Freire and Senghor: “Students will walk away with a greater confidence in their ability to think critically, ask tough questions and seek answers. Our students will be exposed to high-level, rigorous instruction and teachers will have a starting point for next time! I’m excited for my students to engage in a reflective research project that will give them information that helps them navigate through their individual lives and circumstance. It’s good to see them working on a project where we can meet each learner where they are and scaffold their individual growth to the next steps.”

For my part, I’m always down for a new experiment that will offer agency and voice to young people. I can’t wait to hear – and for you to hear – the voices of the young men of MCAP. Stay tuned. I just hope that everyone is ready and willing to listen.

© Photo

Dominic Inouye